loading

loading

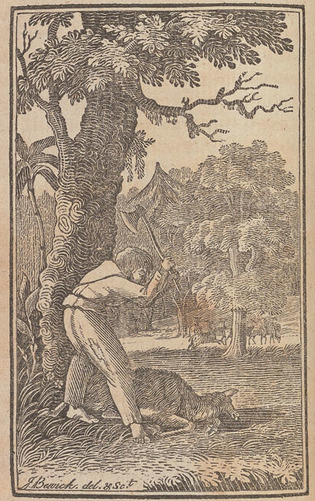

Arts & CultureRobinson Crusoe through the agesObject lesson: A lesson in ethics, with llamas. Jill Campbell ’88PhD is a professor of English at Yale.  Beinecke LibraryIn the 1788 book New Robinson Crusoe, the famous castaway spots a herd of llamas and immediately kills one. But as the tale goes on, Crusoe decides to change his approach. View full imageCrusoe’s axe hangs in the air above the young llama he has felled. Having spotted a flock of llamas on his island, he found himself overcome with “a violent desire to eat some roast meat, which he had not tasted for a long time,” and waited in ambush until a llama wandered close enough to kill. The episode exemplifies Robinson Crusoe’s famed self-sufficiency; anything he needs or wants to consume, he must provide for himself. Yet if you pause to think over what you recall about Robinson Crusoe, you might ask yourself whether you had been aware that llamas are among the wildlife on Crusoe’s island. Goats, yes: Crusoe makes himself clothing and even an umbrella out of goatskins, which became part of the iconic images of him you may have seen. But llamas? In fact, although it features Robinson Crusoe, this engraving by John Bewick, from a volume in the Beinecke Library, is an illustration not for Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) but for a work entitled New Robinson Crusoe; an Instructive and Entertaining History, for the Use of Children of Both Sexes (1788)—one of numerous translations of Joachim Heinrich Campe’s Robinson der Jüngere, first published in 1779. Campe’s book, which circulated widely in multiple languages for more than a century, is the first in a series of almost countless imitations and transformations of Robinson Crusoe for young readers, ranging from the perennially popular Swiss Family Robinson by Johann Wyss (1812) to William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (1954). Adaptations of Defoe’s story of the resourceful castaway on a desert island are so numerous that they have elicited a genre name of their own—the “Robinsonade”—and authors, parents, and teachers have often assumed that such stories are of particular value for young people. Most Americans recall reading Lord of the Flies as a school assignment and debating its implications about “human nature” in class. Many adults fondly remember their childhood experience of Swiss Family Robinson, on the other hand, as an introduction to the pleasures of reading: transported to an unfamiliar land, absorbed in the adventures of the family there, the young reader finds that island, remote as it is, veritably crammed with possibilities of discovery and delight. The island thus offers a vivid emblem of the space of reading. Like the island settings of many Robinsonades, it is particularly crowded with animals: many of the family’s adventures revolve around their encounters with one or another exotic animal—flamingos, penguins, and many more—which they either tame or kill, or sometimes both. From its origins in the eighteenth century through the present day, children’s literature has taken animals to be of special interest to young people, and early children’s books often dwell explicitly on ethical questions about the proper relations between humans and nonhuman animals. The scene of Crusoe depicted here, for instance, leads into a discussion of whether it is immoral to kill animals for one’s own benefit. When, somewhat later, Crusoe realizes that he will gain more by taming llamas for use and companionship than by killing them, the narrator treats this recognition as a great advance. Through the figure of the llama, he also intertwines this discussion of the proper treatment of animals with reflections on the questionable morality of the Spanish conquest of the indigenous people of Peru. In this and other Robinsonades, authors link the topics of the treatment of animals and of colonized peoples, posing questions of historical significance through children’s fascination with animal-kind. Tellingly, when Karl Marx cites Robinson Crusoe to illustrate a point in a famous passage of Capital, he mistakenly refers to Crusoe’s taming of llamas rather than goats—suggesting that his ideas about political economy were first stirred by his childhood reading of the Robinsonade illustrated here.

The comment period has expired.

|

|