loading

loading

featuresThe search for a pastJenna Cook ’14 went to China looking for her birth parents. She found two thousand families who were looking for their daughters. Cathy Shufro teaches writing at Yale.  Chutian Metropolis DailyJenna Cook ’14 put up 800 posters in Wuhan, China, in her efforts to find her birth family. Behind her, a passerby is reading the poster. View full imageJenna Cook’s mother tells this story: Jenna is maybe three years old, strapped into her car seat in the back of the family’s Honda Civic, and she says, “I miss my mother.” From the front seat, Peggy Cook replies, “I am your mother,” and Jenna says, “No, I mean my Chinese mother.” Jenna Cook recalls, “At a young age, I was thinking about the people and the culture that I left behind when I immigrated to the US.” Cook, who would graduate from Yale College in 2014, was born in central China 25 years ago and adopted as an infant. She grew up in Newburyport, Massachusetts, the older of two Chinese adopted daughters of an elementary school teacher; she was named after a favorite student. Consciously or not, Cook began preparing to look for her original family at age 14, when she chose her high school for its excellent Mandarin program. She visited China twice with her mother and sister and once to volunteer at the orphanage where she came from, and she continued studying Mandarin at Yale. She won a Light Fellowship, which funds language study in East Asia, and spent her freshman summer in Harbin. By sophomore year, she felt ready to look for her family. “I thought, ‘Maybe I have accumulated the language skills and gone to China enough times that I have friends there and feel comfortable,’” she recalls. “Searching seemed realistic.” Still, when Cook went to her hometown of Wuhan during sophomore summer, she kept her expectations low. In a city of 10 million, she did not imagine she’d find her family on the first try—or even find them at all. She could never have foreseen what did happen: after an article about her search appeared in a Wuhan newspaper and catalyzed nationwide publicity, more than 2,000 families sent her messages via e-mail and Weibo (similar to Twitter). Cook met with 50 families whose stories best matched hers. One family traveled three days and nights by train; others simply walked up the street to meet her. All came in hopes that they might embrace the daughter they had relinquished 20 years before.

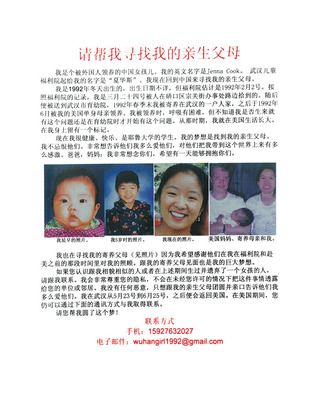

The heading on the poster reads, “Please help me find my birth parents.” The photo at far left is the earliest picture of Jenna. It’s followed by photos of her at five, at twenty, and with her American mother—Peggy Cook—and her foster mother in Wuhan. View full imageCook was one of hundreds of thousands of Chinese babies who were bundled in quilts or cradled in baskets and left in front of police stations, at outdoor markets, and on household doorsteps. This deluge of foundlings began in 1980 with China’s one-child policy, instituted nationwide that year and rescinded only in October 2015. Its primary aim was to increase per capita GDP by curbing population growth. Despite the limit on children, many families did have more than one child, in part because enforcement waxed and waned in rural areas. And certain people were allowed to have two children—such as farmers with a first-born daughter, who could try for a son. If the second child was also female, they might give her up in hopes that the next pregnancy would yield a boy. This preference for males derived from both pragmatism and culture: boys could provide muscle on farms, and they would carry on the family name, perform ancestral rituals, and, crucially, support their parents in old age. Although Americans might assume that most of these babies went to Western households, the vast majority remained in China. Only after 12 years did the Chinese government permit international adoptions. China opened that door in April 1992, and two months later, Peggy Cook took infant Jenna home. Jenna was in the first cohort of an estimated 140,000 children born in China who would join new families in Europe, Australia, and North America, most of them—85,000—in the United States. As these Chinese-born Westerners come of age, Cook may be a forerunner in a wave of young adults who will travel to China in search of their lost parents and grandparents, their unknown sisters and brothers.

Chutian Metropolis DailyJenna with her mother, Peggy, when the two visited Wuhan in 2012. View full imageCook arrived in Wuhan with her mother Peggy in May 2012, with meager clues about her origins. She knew only what was written in her file at her orphanage: she’d been picked up in March 1992 on Zong Guan Street, near Wuhan’s long-distance bus station. “I don’t know how old I was,” she says. “I don’t know what I was wearing.” She says the motivation for her search was simple: “When you lose touch with someone for many years and you don’t know where they are in the world, you wonder how they’re doing, and if they are OK.” Through a friend of a friend, Cook arranged an interview with the Chutian Metropolis Daily of Wuhan. On May 25, the newspaper published an article describing Cook’s search, along with photos of her as a baby and as a college student and the number for a telephone hotline. News of her search traveled far, picked up by other newspapers and posted online. The deluge of messages and phone calls came from every Chinese province and from overseas. “The younger generation—my siblings or cousins—are very Internet-savvy,” says Cook. The 50 families she interviewed had all gone to Zong Guan Street in March 1992 and left a daughter there. Mostly they were couples accompanied by a son or daughter, or sometimes by another relative. Four fathers came alone, as did one mother. One couple arrived with their three children, a brother-in-law, and a nephew. Many of those who came embraced Peggy Cook and thanked her for raising Jenna. Most of the families had lived in towns and villages around Wuhan in 1992. They’d taken their daughters to the city to give them the advantages of an urban upbringing. “A lot of them said they wanted this child to have a better life, and because of the household registration system—the hukou system—there are very big differences between being a city person and a rural person, differences that will affect you for your entire life,” says Cook. “What these parents imagined for their daughter, in the best-case scenario, was to be picked up by someone in the city. She would grow up as a city person.” What Cook heard accords with research by Hampshire College professor Kay Ann Johnson, who writes that parents acted strategically when they gave up their babies. They might leave a child at the household gate of a childless family that could legally adopt, or a family wealthy enough to pay the fine for an extra child. Often, the mother or father would light a firecracker to ensure that the baby was found. Cook collected the stories she heard. Some families told Cook they had been too poor to feed a second or third child. One husband and wife had given up their child because they were young and unmarried; when they did marry, they had two more children. Another couple had wanted to keep their daughter, but when they returned from work one day the grandmother informed them, to their horror, that she had left the child on the street. The grandmother later committed suicide by drinking pesticide. During these interviews and, later, when doing research as a Fulbright scholar in China, Cook observed that the decision to give up a daughter had been traumatic for many families, and that the one-child policy had often played a prominent role, directly or indirectly. This confirmed what Johnson writes in China’s Hidden Children: “There have been very few healthy children in the China adoption program who were truly voluntarily relinquished.” Parents who tried to hide forbidden babies faced crippling penalties: destruction of household furniture, fines equivalent to years and years of annual income, lost jobs, forced sterilization. And yet, Johnson writes, mothers camouflaged “out-of-plan” pregnancies. Some hid their babies, even though unregistered children were barred from all but rudimentary schooling and would be unable to get jobs. Some parents secretly passed their infants to relatives or other families—though the government had made such adoptions illegal, to discourage unsanctioned births. Cook says the families she spoke with were shocked to find out that she had grown up thousands of miles from Wuhan. “None of them had heard of international adoption at all. They had no idea their daughter could be living on the other side of the world.” (Even well-educated professionals have told Cook that they knew little or nothing about the large numbers of children adopted abroad. “I’d tell them that 140,000 children from China are living around the world. They’d be, like, ‘No way! That many?’”) It seemed every couple had hoped that their lost daughter had been taken in by some family in Wuhan. “And actually some of them in later years went back to the city looking for her, thinking that she would be there.” She met one mother who, even before she gave her daughter up, had hoped for a reunion. The woman showed Cook a scrap of blue-and-red checkered cotton that, she said, matched the homemade clothing in which she’d dressed her baby on the day she “lost” her. The family had been impoverished and already had three girls: “We needed a boy,” the mother said. In an article Cook wrote for Foreign Policy in March 2016, she recounts what the woman said next: “I dressed you in the new clothes for good luck. I kept this scrap for 20 years to remember you. My little baby, you must have seen this cloth before! You must have the matching clothes?” She began to cry. Although 37 of the families Cook met with had DNA tests to find out whether she was their daughter, she did not find her birth family. And yet, she feels that by meeting those not-parents from 50 families, she came to see who her own parents must have been: ordinary people. “When they walked into the room, they were just like people you would see on the street, human people like you and me.” Her hope had been partly to reassure herself that her parents were “doing OK,” and she found that the parents who sought to meet her wanted to know the same thing about their lost daughters. “They said, ‘We just wanted to know our daughter’s OK. We just want to know if’—it’s so hard to translate—‘if she’s passing her days well.’”

Yenching AcademyJenna is currently working toward an MA at Peking University’s Yenching Academy; she enjoys living in a society in which her race is unremarkable. View full imageCook began her scholarly study of adoption during sophomore year in a class called Adoption Narratives, taught by Professor Margaret Homans. Two years later, Homans was Cook’s adviser for her senior essay in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, based partly on her interviews with the 50 families. Her essay, “Constructing Kinship: Longing, Loss, and the Politics of Reunion in China,” won four Yale prizes, including the Williams Prize in East Asian Studies and the John Addison Porter Prize, given for a senior essay of “original effort” and “general human interest.” When Cook went to Wuhan in 2012, she still sounded like a foreigner. These days, she speaks Mandarin without an accent. “I’m starting to read novels, things regular Chinese people read,” she says, exultant. She lives in Beijing, where she’s working toward a master’s in China studies—reclaiming the culture she left behind. Cook has not decided what she’ll do after completing her all-expenses-paid program at Yenching Academy in Peking University (whose students Inside Higher Ed calls “the elite of the elite”). But she does hope to find a career that will allow her to spend time in both China and the United States. She credits the encouragement of her Yale professors and Yale’s financial aid and research fellowships for helping to put her on her current path. “I am deeply grateful for the educational experience that I received while at Yale,” she says. As an Asian living in China, Cook finds release in no longer being in the minority. She always felt acutely visible growing up in mostly white communities and as the Chinese child of a white mother. Now, she says, she enjoys living in a society in which her race is unremarkable. She and another adopted Chinese American, Laney Allison, are writing a free online manual to help others search for their birth parents in China. (It will be posted on the website ChinasChildrenInternational.org; click on “Projects.”) Although Cook isn’t looking for her own parents at the moment, she feels that she has made a connection nonetheless. “Almost five years later, looking back, I have a sense of them, because I met so many other families,” she says. “I feel satisfied that I tried my best to find them. I think the best way I can show my love for my Chinese family is to move forward and live my life to the fullest, doing what I love to do. I think this is what my birth family would want for me.” She appreciates one reminder of her babyhood in China: the name the Chinese orphanage director chose for her 25 years ago. The director gave the family name “Xia” to all the children brought to her in March 1992. And she gave the girl who would be Jenna the first name “Hua Si.” Read in reverse, Xia Hua Si means “remember China.”

|

|

11 comments

-

Olivia Hoopes, 11:40am January 04 2017 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Darlene McHale, 4:33pm January 05 2017 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Karen Krieger, 5:03pm January 18 2017 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Mark Branch, 1:36pm January 19 2017 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Steven Jent, 10:41pm January 25 2017 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Carroll Roblin, 12:02pm January 26 2017 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

colleen gillies peterson, 1:54pm January 26 2017 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Roger Warren, 1:42pm January 27 2017 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Rex Armstrong, 11:39pm January 27 2017 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Wesley Hagood, 9:49am January 28 2017 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Esperanza Rodríguez , 9:43am February 06 2017 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.This was so beautiful Jenna, and made me cry. Thank you

Jenna thank you for your article, my husband and I adopted our daughter from China in 2004 in Nanning China. she will be 14 this year and we are headed to China in March for a two week tour,beginning and ending in Beijing, she will visit her orphanage as well. She to takes Chinese 5 days a week at her school so this will be good practice for her. Her name is Emma but her chinese name was Xia Yu.

She is hopeful to find her Chinese family as well one day but this article that I will share with her I believe will be very helpful to her.

I wish you the best and thank you again for sharing this wonderful story with us

Best

Darlene McHale

We also are parents of a Chinese daughter, adopted in 2005 from Gaoyou, Jiangsu province. She just turned 12 and this gives all of us hope that she might eventually find her birth family. Her orphanage is closed down now but we will take her back to see it. With permission I would like to share this article with FCC (Families with Children from China) groups and on Facebook. It has meaning and ramifications for a much larger community than Yale. Please let me know if this is permitted. Thanks.

Please feel free to share links to the article! We’re happy to have it read far and wide. —Mark Branch, Executive Editor

Amazing story. I am an adoptee myself and am blessed to now have a relationship with my birth mother having reconnected with her and her family when I was in my late thirties. Now as a father to two beautiful daughters adopted from China it has always sadden me to think that they may never have the opportunity to reunite with their biological families. The hurtles simply seemed too great. This story gives me hope.

Thanks for this story of pain, longing, acceptance, hope and above all love in abundance. I will share this with my daughters.

I am curious about the parents who had never heard of international adoption. I have read before that many parents have underground connections and have an idea of their child's whereabouts. Have you any knowledge about this?

Thanks

Thank you for this article! We have a beautiful and wise and strong and the list goes on....daughter who we adopted at the age of 2 from China! We will return and we will never stop her from doing what she feels in her heart to do regarding her desire (if she so desires) to track down her loving birth mom! xo

Thank you so much for sharing this incredible love story. We also are adoptive parents from China with a daughter 17 and 13, and often wonder what the Chinese mother/family perspective was. I have been told that this is a different culture and it not viewed the same with them. I could never get my head around that.

On our oldest daughters recent 17th birthday it was on my heart to write her a message, I do believe it is a message the mothers of the abandon daughters of China live everyday. It is meant as a love letter to our daughter written in that spirit and your account confirmed that for me. I wanted to share it with you so in have included it. Thanks you again so much.

Somewhere in China ~

On this morning as she has every June 6th since 1999 a mother near Tongling, China visits the empty space in her heart. She wonders what the baby girl she carried to birth is awaking to on this her birthday. Is she safe, is she happy, does she ever think of me? Does she question why, how her mother could have allowed this to happen? Does she understand, but how could she know? Does she share the same endless heart-ache as I?

Again she remembers as her daughter took her first breath, her soft cry and then the silence as she was taken away, the never-ending silence. She holds tight to these moments never allowing them to fade.

The thoughts and questions press her heart, many of which are frozen in her being--the loss, the pain, but mostly the shame. The shame, sometimes in the early morning, when she lays down at the end of her day in the still darkness. When she hears a baby’s cry or sees another with child and her heart is taken back once again.

If only for a moment I could see her, touch her, explain the unexplainable. Hold her hand while I stroke her hair--kiss her soft cheek. Ask if she is warm at night with plenty to eat, and tell her how beautiful she is, hoping to see myself in her eyes. Does she look like me?

But mostly I would say how much I love you, how I miss you each day. How I wish you could know who I am and how I keep the brief moments I had with you in my heart.

Good night sweet girl, I’ll think of you again tomorrow.

My wife, Leslie Roberts (Yale Law '72), and I have fourteen children, two who joined our family by birth and twelve who joined by adoption in China between 1996 and 2012. I am intrigued by Jenna's affecting account of her efforts to find her birth parents. Three of our Chinese children are true orphans; the other nine were abandoned for reasons related to their sex or health. All of our Chinese children are bilingual in English and Mandarin, and all but the youngest (and last) of them have returned to China to visit or study since their adoption. As it turned out, six of them are girls and six are boys. I have read Professor Johnson's books and monographs on the abandonment and adoption of children in China, and I am acutely aware of the emotional pain and trauma that our children's birth parents experienced in abandoning their children. My hope is that our children who wish to undertake the effort (none of whom have yet expressed such a desire) will be able to find their birth parents and assure them that their abandoned son or daughter found a path to a satisfying and productive life.

I am becoming convinced that the best way to re-connect with birth parents will be DNA matching.

Anyone who is interested in finding the birth parents of adopted Chinese children should have their child's DNA tested and placed in as many DNA databases as possible including 23andMe.com and Ancestry.com in the USA and WeGene in China. They should also upload their DNA profile in the GED Match database.

It is only a matter of time - as these databases grow in size our children will find relatives who will be more closely related than those you can find at this point in time. The growth of the databases will allow more and more family reunions over time.

Wes Hagood

Adoptamos a nuestra hija en julio de 2005. La recogimos en Naning, pero vino del orfanato de Wouzhu. Alguien sabe si se pueden obtener más datos de las niñas de este orfanato desde el día que las recogieron hasta el día de la adopción? Gracias