loading

loading

Letters to the EditorReaders weigh in on the Trump Administration, the joys of travel, and moreWe welcome readers’ letters, which should be mailed to Letters Editor, Yale Alumni Magazine, PO Box 1905, New Haven, CT 06509-1905; e-mailed to yam@yale.edu; or faxed to (203) 432-0651. Due to the volume of correspondence, we are unable to respond to or publish all mail received. Letters accepted for publication are subject to editing.  View full imageThe new Trump administration’s lack of experience, lack of competence, and sheer arrogance, combined with the magical thinking of much of the electorate, is a prescription for disaster on many levels (“The Next Four Years,” January/February). There is a vast gap between the expectations of voters and the new administration’s ability to effect change. Disruption alone is not a miracle cure for what ails us. There have to be actual plans, workable solutions, possible areas of compromise, hard work, soul searching, and patience in any government looking to effect change. “Just say no” has never worked in the past. It is doubtful that it will work in the future. Lucile Makowsky Lichtblau ’56MFA

Professor Robert J. Shiller’s totally gratuitous invoking of Mao Zedong’s “Great Leap Forward” in his otherwise intelligent comments really shows just how political the practice of economics can be, even when it is practiced by a Nobelist. His first five paragraphs discuss the difficulties of achieving high GDP growth over sustained periods and point out that presidents, in general, have not been able to “promote economic growth,” other than “by not provoking financial crises or other disasters.” Fair enough. The remainder of his comments, save for the paragraph on Mao, discuss the roles of inspiration and psychology in economic affairs and conclude with doubts about whether Trump will be successful “at achieving his promised economic growth.” Again, fair enough. But totally out of the blue, in his second-to-last paragraph, Shiller asserts, with virtually no supporting logic other than a passing reference to Trump’s “attitudes toward immigrants and minorities,” that there is a risk that his plans will turn out to be another “Great Leap Forward.” Not fair enough. Indeed, not fair at all. Mao’s so-called “Great Leap” involved forced collectivization, socialist tyranny, and brutality. Alas, it achieved little more than a famine of monumental proportions. What is there in anything that Trump has suggested, including his sometimes politically incorrect comments about immigrants or minorities, that could possibly produce anything approaching this in the United States? Richard R. West ’60

The Yale Alumni Magazine asked Professor Shiller for a response. He replied: “Admittedly, comparing Trump’s program with Chairman Mao’s Great Leap Forward (1958–62) is probably overstatement. In many senses the two programs are just opposites. I actually give Trump’s program a chance of succeeding in producing higher economic growth. “But there are similarities between Mao and Trump, and a potential for some kind of disaster from Trump. Both “The Great Helmsman” and Trump showed an unnatural sense of their own unique infallibility, and, amazingly, convinced many millions of people of this. Both were hasty and rash in their impulse to make big changes. They both encouraged demonization of some segments of the population. In the case of Mao it was Chinese business-oriented people (capitalist “running dogs”). In the case of Trump, it has been Mexicans, Muslims, liberals. They both encouraged warlike sentiment. I worry that Trump could spur a new nuclear arms race among nations, which could conceivably be an even worse disaster than the Great Leap Forward was.

Early adoptersAs adoptive parents of three Chinese daughters, my wife and I enjoyed reading about Jenna Cook’s efforts to find her birth parents (“The Search for a Past,” January/February). We would, however, correct the statement that China opened the door to international adoptions in April 1992. We traveled with a group led by the Waltham, Massachusetts, agency Wide Horizons for Children in November 1991 to adopt our daughter Taegan in Changsha, Hunan. I think we were the first group to go to China from a US adoption agency, although I know that some parents did travel on their own prior to that. Our daughter, Taegan, now 25, is currently teaching first grade in Taipei. Mark Williams ’70, ’06PhD

China’s first law formally permitting international adoption took effect in April 1992. Thank you for letting us know that you were among the pioneers who predated that law.—Eds.

Witness to historyYour review of Nancy Malkiel’s Keep the Damned Women Out (Reviews, January/February) ends by stating that “many other all-male schools quickly followed Yale and Princeton’s lead.” This reminded me of a personal story. I went to an all-male boy’s prep school in New Jersey, physically situated adjacent to a girl’s “sister” prep school. This was the late ’60s, and all manner of societal changes were occurring. My last year there, I was on a student committee urging the two schools to merge into one coeducational school—which they did just after I left in 1972, entering a Yale that had been admitting women for only a couple of years. (The merged high school, now the Dwight-Englewood School, is, incidentally, named after Timothy Dwight.) My grandfather was a founding trustee of Claremont Men’s College, created at the end of World War II to educate returning (male) GIs. Thirty years later, in the mid-’70s, their board started contemplating going coeducational. So my grandfather decided to do some due diligence: he came and visited me to ask my friends and me about how coeducation was working out at Yale. We all told him not to worry; all was fine. He then traveled up to Dartmouth to visit with a high school classmate of mine whom he also knew, to ask the same questions. He got similar answers there. Shortly thereafter, Claremont Men’s College began admitting women. But they didn’t take the “Men’s” out of their name until five years later, when it was renamed Claremont McKenna College—a necessary change that conveniently preserved the place’s initials, “CMC,” by which all its alumni/ae refer to it anyway. Doug McKenna ’76, ’78MS

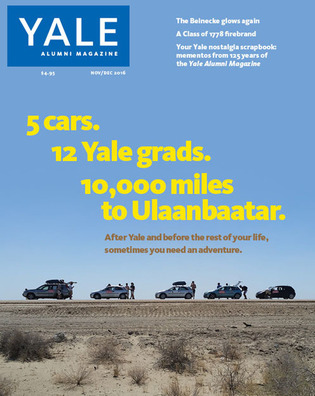

View full imagePost-grad adventuresThe Mongol Rally (“5 Cars. 12 Yale Grads. 10,000 Miles to Ulaanbaatar,” November/December) sounds like a wonderful experience for the 12 grads: a way to see and be with local peoples, and also a challenge physically with mechanical breakdowns in unknown parts of the world. In 1960, I spent a year in the Army in Korea after the war had ended. Since the Army got me halfway around the world, I thought I would go the rest of the circle tour on my own using freighters, train, local cabs and buses, and walking (plus one short plane trip). In the process I went from Japan to Hong Kong to Singapore to Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, India, Pakistan, Iran, Turkey, Syria, Jordan, Israel, Italy, Germany, and then back to New York on a troop ship. It was fabulous. I hope other graduates have a similar experience before moving on in their lives. Peter Capra ’57

Your article on the Mongol Rally carried the tag line “After Yale and before the rest of your life, sometimes you need an adventure.” Indeed, after graduation from Yale in 1968, I had an adventure. I began graduate study at Stanford, but at the request (“You are hereby ordered . . .”) of my draft board, I postponed my plans, entered the Army, and had a yearlong adventure with the First Cavalry Division as an infantryman in a free-fire zone in Vietnam. I survived this adventure and returned to Stanford, followed by 35 years as a Georgia Tech mathematics professor. Many of my friends were not as fortunate. Alfred (Fred) Andrew ’68

Adventures like those described in your article need not be confined to “after Yale and before the rest of your life.” Travel in some of those parts of the world can always be an adventure, as I know from taking a small passenger plane en route between Osh (Kyrgyzstan) and Dushanbe (Tajikistan) at the time of the coup against Gorbachev in 1991, where the cockpit crew had to clamber over our duffels full of climbing gear “stowed” for the flight in the aisle of the passenger cabin; from sitting in the cockpit of a Russian airliner that missed its approach when landing at Sheremetyevo outside Moscow; from driving across the trackless western Mongolian steppe in a jeep which dropped its drive shaft (2005); and again (2007) in Mongolia, being stranded overnight in the middle of nowhere by a broken fuel pump. Little did I know that studying Russian and Russian history at Yale would lead to so many adventures, the most memorable of which may have been, at age 54, riding a mountain bike across 12,000-foot passes on a route from Kyrgyzstan to Xinjiang and down into Pakistan. You’re never too old for the excitement and education of travel! Dan Waugh ’63

Calhoun—and TildenI can’t quite understand why Yale has such difficulty deciding whether to remove John Calhoun’s name from a college (“Calhoun Decision Will Be Revisited,” January/February). Calhoun defended slavery, owned numerous slaves, wanted to add to the number of slave states, and advanced the poisonous doctrine of nullification, moving the country toward Civil War. No one claims he did anything special for Yale. Why would anyone believe such a person deserved to be honored by Yale? The same issue offers a good alternative: Samuel Tilden (“Another Almost-President”). He was anti-slavery but embraced Lincoln’s call for reconciliation after the Civil War. He rooted out party corruption as governor of New York. He was “widely known for his dignity and good nature.” He won the popular vote for president but was cheated out of the office by a sellout in the Electoral College, based on a plot to deprive blacks of the political power they gained after the war. Naming a college for him might pave the way someday for naming a new college for another Yale graduate and Democrat who won the popular vote but was deprived of the presidency in the Electoral College by an opponent whose campaign catered to hostility to minorities. Donald G. Marshall ’71PhD

See page 18 for our report on the decision to change the name of Calhoun to Grace Hopper College.—Eds.

Win some, lose someI was thrilled to find, for the first time that I can remember, the proper use of the verb “to segue” (“They Never Said ‘Don’t Drink the Water,’” January/February). Having had to listen to the media anchors constantly advertising their ignorance of being unable to tell a noun (Segway) from a verb (to segue), it was refreshing to discover at Yale no such ignorance. Thank you! However, on another note, it was disappointing to find, in an advertisement on page five of the same issue, what is obviously a theater but was termed an amphitheater (two theaters facing each other). It seems that fewer and fewer people take Latin these days. Steven S. Hall ’63E

Think responsiblyIn his Freshman Address (Countering False Narratives,” November/December) President Salovey invites the incoming Yale College student to grow to be “a more careful and critical thinker.” He encourages independence in learning “to evaluate evidence, to deliberate more broadly and more carefully, and to arrive at your own conclusions.” While taking a fresh look at accepted narratives is a heartening approach to finding new truths, a lesson I value from my divinity education lies with the recognition that sometimes I should respect an existing narrative that does not sit easily with me. Repudiation is not refutation. Reshaping narratives responsibly requires all the good qualities of inquiry that Salovey has summarized. It involves engaging with those who are knowledgeable in a field of inquiry, and allowing to them full credit for all of their expertise. When I have read, in recent years, some alumni letters responding to our magazine’s articles regarding climate change, it has been my sense that these alumni missed this hard-won lesson of my education at Yale, that truth, and truthful conversation, are not well served in summarily rejecting what is discomfiting to receive. We might all do well to become climatologists, learning from and testing that field of inquiry from its beginnings in the nineteenth century right up to today. But for those of us who lack world and time in which to wrestle with every lesson and advance of the science, I find it behooves us to begin dialogue on such a fraught and urgent matter as global warming with an attitude of respect for the credentials and expertise of the practitioners who tell us what we do not want to hear. For Yale alumni to try to kill the message that the scientists bring does not speak well to me of our university, in its stated aspirations for lux et veritas. Mary H. Hall ’81MDiv, ’86STM

CorrectionIn an article about students applying to transfer to Pauli Murray and Benjamin Franklin Colleges (“Pioneers for the New Colleges,” January/February), we incorrectly reported that Morse and Ezra Stiles Colleges opened in the fall of 1963. In fact, they opened in the fall of 1962.

|

|

1 comment

-

Barnet Schecter YC'85, 10:11am March 16 2017 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.Yale is better off without a Tilden College. Tilden's strategy for the Democrats after the Civil War was "condemnation and reversal of negro suffrage.” In the election of 1876, Tilden’s victories in the South were fueled by Klan violence and intimidation that kept black and white Republicans away from the polls. Had Tilden become president, the result for African Americans would have been the same: The withdrawal of federal troops from the former Confederacy and the demise of Reconstruction, the Republican program of freedom and equality for blacks that was born with Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and died with the Compromise of 1877. The end of Reconstruction brought nearly a century of Jim Crow rule in the South. Today, with renewed efforts to suppress minority votes, the history of Reconstruction is vitally important.