loading

loading

featuresHow to commemorate catastropheRemembering World War I, 100 years after Jay Winter, the Charles J. Stille Professor of History Emeritus, specializes in the study of World War I and its impact on the twentieth century. He is the author or coauthor of a dozen books.  Three Lions/Getty Images1914 gave birth to one of the iconic figures of the twentieth century and after: vthe refugee. Here, Belgian refugees in a French town in 1915 read messages written in Flemish by other refugees. View full imageOne hundred years after the United States’ entry into the 1914–18 world war, what aspects of this vast global conflict, and of America’s role in it, are worthy of commemoration? First and foremost, we remember the ten million men all over the world who lost their lives in the war. Indeed, remembering this “Lost Generation” is big business today. Millions are being spent on memorial sites and ceremonies around the globe. Millions of people pay considerable sums to get to them. And yet the ubiquity of commemorative gestures hides a predicament: is it possible to honor the men who died in war without glorifying war itself? I believe that it is possible—indeed it is essential. One way is to recognize the yawning gap between the ordinary decencies of the men who went to war and the blindness of the men who led them into a kind of battle the world had never seen before, a kind of battle they could not control. Their errors, their blindness, their arrogance—in some cases, their criminal incompetence—sentenced millions to hardship, mutilation, and death. Remember that half of the ten million have no known graves; their bodies were blown to pieces by the greatest collection of artillery the world had ever seen. Fifty years after I first started to study the Great War, I still feel a kind of cognitive dissonance when I speak of it: how can we understand so much suffering for so little reason? The poignancy of much war remembrance derives from this simple reflection, that the men who ran the war unleashed something that was beyond their comprehension and that they were unable to control. The Great War moves us for this reason alone.

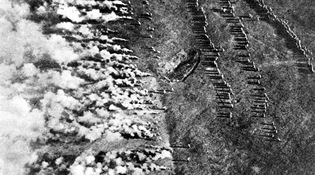

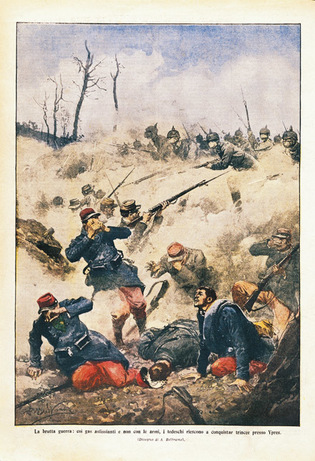

Imagno/Getty ImagesJewish refugees from Russia gather in a camp at the Austrian-Russian border in Galicia, around 1915. The magnitude of the refugee flow in the Great War was unprecedented. View full imageThe central questions today are what, when, and where to commemorate. I look at these questions in terms of what I would like to call the degeneration of war. Between 1914 and 1918, the rules under which armed conflict is conducted were transformed in such a way as to expand the number of its victims exponentially without shortening its duration by a single day. This double outcome is what I mean by degeneration. One key element in this process was the obliteration of the distinction between military and civilian targets. That nineteenth-century norm did not survive the German invasion of Belgium and northern France in 1914. Atrocities were by no means a German invention; they were simply built into German war plans. The German army could not traverse the most densely packed population in Europe and meet its strict timetable of advance without killing and maiming civilians and responding to perceived (though unreal) resistance with an iron fist—a policy they termed Schrecklichkeit, ruthless terror. For decades German observers presented these charges as pure propaganda; we now know that they were true. Both on the Eastern front and on the Western front, 1914 gave birth to one of the iconic figures of the twentieth century and after: the refugee—man or woman, elder or child, traversing Europe to get out of the way of the armies. This in itself was not new, though the magnitude of the refugee flow was unprecedented; what mattered was that many of these people became the targets of both sides. In the case of the Russian retreat of 1915, refugees became the targets of their own armies. Falling back after a major defeat, the czar’s soldiers killed between 50,000 and 100,000 Galician and Russian Jews. The victims termed this catastrophe the Drittr Hurban, or the Third Disaster, giving it the magnitude of the destruction (twice) of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem. John Reed, later the chronicler of the Russian revolution, brought this story home to readers on both sides of the Atlantic. A new kind of continent was born in 1915, felicitously termed “Refugeedom” by historian Peter Gatrell, a place where there are no laws and survival depends on a whim or on the generosity of more fortunate people. Gatrell shows the profound destabilization of the Russian empire through massive population displacement from the very first months of the conflict. These refugees scattered everywhere. And there were many others. In the very first year of the war, one million Belgians—out of a population of eight million—left their country. In 1915, similar numbers fled the invasion of Serbia by the Central Powers. In 1917, it was Italians who fled en masse after the German and Austrian breakthrough at Caporetto. Refugeedom, created in 1915, grew rapidly in later years. It is with us still.  Print Collector/Getty ImagesBelgian refugees at the Ostend harbor in 1914 wait for a boat to take them to England. World War I saw the obliteration of the distinction between military and civilian targets. View full imageIf refugees were men and women largely without protection, what protection was there for those living as despised minorities in multiethnic empires that were engaged in a fight for survival? After 1914, every country tried subversion of their imperial enemies through appeals to disgruntled minorities: to the Irish in the United Kingdom, to the Czechs in Austria-Hungary, and most notably, to the Armenians in the Ottoman empire. The quarrel between ethnic Armenians and Ottomans had been simmering for years; periodic eruptions of anti-Armenian violence had raised doubt in the minds of the triumvirate that ruled Turkey in 1915 as to the loyalty of the two million Armenians who had lived in the Ottoman empire for centuries. It is true that some Armenians fought in the Russian army in the Caucasus in 1914, where the Turkish army suffered a severe defeat. But the fear of what would later be termed a “fifth column” was a fantasy, and would become a genocidal fantasy in 1915. April 24 and 25, 1915, form a turning point here. On those days two decisive events unfolded. The first was the Franco-British invasion of Gallipoli, in Turkey. After a failed naval campaign to force the straits of the Dardanelles, the Allies—at Winston Churchill’s instigation—decided on launching an amphibious operation to land on the western peninsula of Gallipoli, take the heights above it, and then proceed to Constantinople, several days’ march to the north. Nothing of the kind took place. The landing, on the night of the 24th and morning of the 25th, was botched—leaving the troops facing near-vertical cliffs they had to scale. They never managed it, and the operation turned into another version of the stagnant war of position on the western front at the time. The Turkish commander who blunted the invasion, Mustafa Kemal, became a national hero and legend: Ataturk, the father of his people. Meanwhile, those who suffered at the cutting edge of the defeat were not only British and French troops, but also Australian and New Zealand troops; by shedding their blood and performing with unquestioned courage, they constructed a national myth, one worthy of two independent nations. Thus the apogee of empire—drawing troops from the Antipodes to Turkey—was the beginning of the end of empire. Australians and New Zealanders share April 25 as joint national holidays, moments of national affirmation. But Turks celebrate on March 18, the date of a battle that preceded the more costly and decisive victory at Gallipoli. For those who are attentive, April 25 cannot escape a darker kind of remembrance concerning Turkey. It was on that date that the Turkish triumvirate sent thousands of messages to their agents in Anatolia to proceed with a plan to uproot and deport two million Armenian villagers from their homes in central and eastern Anatolia. Thus was launched the Armenian genocide, at the very time the Allies landed in Gallipoli. Over one million Armenians, mostly women and children, died in the following months, many driven into the Mesopotamian desert with no chance of survival. German soldiers, allied with the Turks, saw what was happening; even though they reported back to their superiors, both civilian and military, no one acted to stop the killing. It was while reflecting on this crime two decades later that the Polish lawyer Rafael Lemkin invented the term “genocide.” April 25, 1915, is one of those dates requiring commemoration, partly to expose the absurdity of the fact that the current Turkish regime still claims that no such genocide took place. On each and every April 25, we need to break that silence.  Ullstein Bild via Getty ImagesChlorine gas in Flanders, 1915. View full imageIn that same month, three days before, the German army in Belgium released 168 tons of chlorine gas over a front of about four miles. They created a gap in the Allied lines, though German forces were unable to exploit it. They also created a milestone in world history, one which Belgium commemorated in 2015, and which we need to commemorate in future. At Gravenstafel, the farming town where this attack occurred, chemical warfare was born. There had been some similar efforts before, but here was the first full and indisputable use of chemical weapons in combat.  Ullstein Bild via Getty ImagesThe effects of poison gas at the Battle of Ypres, 1915 (drawing by A. Beltrame). The gas tortured much more than it killed. View full imageWhat mattered most was the extent to which gas tortured much more than it killed, and the fact that it tortured soldiers who could not surrender. Battle, Clausewitz taught us, is an attempt to impose your will on the enemy, who then is forced to capitulate. But when gas weapons are used, the option of surrender is closed off. This revolutionizes battle. Battle becomes annihilation by asphyxiation, helped along by any existing wounds. By 1918 one in every four shells fired on the western front was a gas shell. As we can see in Syria today, the world has never been the same since.

How about 1916? On what, when, and where have commemorative events focused? The first is the town of Verdun, in eastern France. On February 21, 1916, the German army under Falkenhayn launched an assault on French fortifications—intended not to take them, but to draw the French army into a battle of attrition which would bleed it white. There is some controversy as to Falkenhayn’s real motives—did he want to take Verdun, but invented an alternative when he knew he could not achieve this goal? Perhaps. But more important than his logic was the logic of the battle itself. It was and remains the longest continuous, unbroken battle in history. It lasted ten months and achieved nothing, other than approximately 700,000 casualties. Nothing in the Second World War comes close to Verdun in its intensity and concentrated ferocity. Not even the second battle commemorated in 2016, the Battle of the Somme, which began on July 1 and lasted for five months. Mind you, the Somme topped Verdun in terms of casualties. Such estimates must be taken with a grain of salt, but whatever the final toll of life and limb on the Somme, it was well above one million men. That was certainly a moment to commemorate. In 1917, the political character of the war changed. On April 2, President Woodrow Wilson asked a joint session of Congress for a declaration of war on the two Central Powers, Germany and Austria-Hungary. The declaration came four days later. For some prominent politicians—former president Theodore Roosevelt among them—that declaration was overdue. For others, it was a dangerous gambit with an uncertain outcome. For President Wilson it was a moral duty, to “make the world safe for democracy” and to put an end to future wars. The greatest impact of this decision was not on the battlefield—though that was to come a year later, when mobilization delivered two million soldiers and the hardware they needed to the battlefields in France. What mattered most was that it significantly bolstered the Allied side of the war just at the moment of the first of two revolutions in Russia.  Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty ImagesWorkers striking in St. Petersburg, Russia, on the first day of the February Revolution of 1917. The unrest grew so great that the czar abdicated and a provisional government was formed. In October, the Bolsheviks would take control. View full imageThe two linked revolutionary moments in 1917 certainly deserve commemoration, though it is likely that the current regime in Russia will ignore them entirely. The second moment—the Bolshevik revolution of late October—completed the first, the overthrow of the czar on February 23, 1917. Propelled initially by a women’s strike in Petrograd on International Women’s Day, unrest grew to the point that the czar abdicated. The new provisional government made a fatal decision to continue the war. After a futile offensive on July 1, which turned into a rout two weeks later, support for the provisional government slowly evaporated. In late October, the Bolsheviks overthrew the provisional government and proceeded to withdraw from the war. The date of October 25 in the old calendar, or November 7 in the new one, ought to be commemorated—not, as it was for 72 years, to mark the birth of communism, but to signal the moment when war bred revolution and counterrevolution at one and the same time.

The year 1918 provides several points on the calendar to mark, though not, I would argue, to celebrate. One is August 8, when the German army gave up any lingering beliefs in victory. The “black day of the German army,” in General Ludendorff’s words, resulted in the surrender of 100,000 German soldiers and in the final roll-up of the western front over the next hundred days. The second is October 23, when Woodrow Wilson demanded regime change as the price of German capitulation. Seventeen days later, on November 9, the German revolution overthrew the Kaiser and launched the first democratic regime in German history. The Kaiser fled to Holland, handing over his ceremonial sword to a shocked Dutch postman. Surrender followed 48 hours later. Representatives of a new regime took responsibility for the defeat engineered by the old regime. The new German republic bore the humiliation of defeat, for which it would be blamed by the Nazis and others who concocted the stab-in-the-back legend. To be sure November 11, 1918, will be commemorated. But it was not the end of the war.  BettmannThousands of Greek residents of Smyrna (the Greek name for Izmir) fled the city as the Turkish army battled British, French, and Greek forces occupying the Anatolian peninsula. View full imageLet me offer a new date for the commemorative calendar of 1919. On May 4, the Chinese delegation at the Paris peace talks received the message that Lloyd George, Clemenceau, and Woodrow Wilson had decided that China’s Shandong province, held by the Germans, would not be returned to China as the Allies had promised. Instead, it would go in the short term to Japan. This was a reward to Japan for the contribution of its naval power in the war; China, torn apart by civil war, had no such claims to make (though the provision of 150,000 Chinese laborers had given the Allies much-needed help in the logistical war). The decision also exposed the hypocrisy of the Allied commitment to self-determination. When Wellington Koo, one of the Chinese delegates in Paris, cabled home the news, he did not receive an answer for several days. The reason was that Chinese students, on hearing of the decision, burned down the telegraph office and much else in Beijing as well. They went on to form the May 4 movement, out of which the Chinese Communist Party emerged. What a day to mark: the day that Woodrow Wilson did his bit to create the Chinese Communist Party.  AlchetronThe city burned from September 13 to September 22, 1922. View full imageThe year 1919 was a time when war changed color: its purpose became one of destroying or preserving the Reds. In Germany, Poland, and Lithuania, a mixed group—freebooters, old soldiers who liked the smell or the thrill of combat, young men who wanted their chance to fight, men of the radical right—continued to wage war, this time against the threat of communism, spreading westward from Russia to Germany. In a period when anti-Bolshevik violence spread from Berlin to Siberia, the hatred of international war was easily translated into the hatred of class war. Let us not forget that the Allies, including Japan and the United States, launched an invasion of Bolshevik Russia in 1919. In effect, this was a war which did not end. Most people think November 11 is the day the guns stopped. Not so; they kept firing all over eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. They fired against massive crowds demanding a say in the peace in Cairo; they fired against demonstrators in Amritsar in India, killing over 1,000 people; they fired on March 1, 1919, against Koreans in Seoul demanding independence from Japan. They fired too all over the Anatolian peninsula, where Mustafa Kemal Ataturk led a refashioned Turkish army to liberate its territory from occupying British and French forces, who left; and against Greek forces, who fled—together with over one million long-term Greek residents of the Ottoman empire. The great fire that destroyed the city of Smyrna (its Greek name) symbolized this catastrophe; that city is now Izmir. What was euphemistically called “population transfer” entailed the forced movement to the east of over one million Muslims previously resident in Europe and the expulsion of a similar mass of Christian Greeks westward toward “Christian” Europe. The date September 22, 1922, when the fire was put out, can serve as a commemorative moment: the day ethnic cleansing became an accepted principle of international relations. The term “degeneration of warfare” seems mild for the human catastrophe these legal terms concealed.  Another Believer/Wikimedia CommonsThe Anglo-Belgian Memorial, in London, was given by Belgium in gratitude to the British for fighting in the Great War and for sheltering an estimated 250,000 Belgian refugees. View full imagePerhaps the best way to mark these dates and to remember the Great War today is through meditation and pilgrimage—to local war memorials, to national ones, to war museums, and to war cemeteries and the battlefields in which they are enfolded. These are the sites of memory of the Lost Generation. I believe that, in our secular age, these sites are the cathedrals of the twenty-first century. They are places where sacred questions are posed, and occasionally answered—eternal questions about sacrifice, death, love, loyalty, betrayal, devotion, suffering. In many parts of the world, more people go to museums than go to church. On a Sunday not long ago, I passed Trinity Anglican Church in Lambeth just after having visited the nearby Imperial War Museum in London, and was struck by the contrast. While secularization has taken its toll on our churches, the sacred has not vanished from our field of vision. The sacred has simply moved out of the churches and inhabits other public spaces. Museums, cemeteries, battlefields, archives, monuments are among them. More in Europe than elsewhere, it is of the 1914–18 war that they speak. This separates Western Europe and the United States, and marks how war today is understood differently by our Allies. Tourism is easy; pilgrimage is hard. Take the hard way, and reflect on the fate of millions of men who did not have the privilege of dying one at a time. Stand where they stood; read the inscriptions on their gravestones. Read the names, because in most cases, that is all that is left of them. Their name liveth for evermore, says Ecclesiasticus. That was the phrase chosen by Rudyard Kipling to mark every single British Imperial (now Commonwealth) war cemetery. Kipling knew of what he spoke: his son vanished during the Battle of Loos in 1915. His son’s name is all that remains. Why do we need a grave specifically for an unknown soldier? The answer is simple. War has always been a killing machine. But artillery, amassed on a scale the world had never seen before, and stalemate on the western front meant that millions of men buried hastily near the front were literally made to disappear between 1914 and 1918. Again: five million men of the ten million killed in the war have no known graves. World War I was the first of the great “disappearances” of the twentieth century, the moment when the restraints, legal and practical, limiting the carnage brought about by war were themselves blown to pieces. Every Armistice Day, let us mark that event with the shock and horror it deserves.

|

|

3 comments

-

Robert E Reynolds MD, Yale 1960, 1:46pm March 18 2017 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Robert E Hammond '65 YC, 12:56am March 23 2017 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

John Gault '66 YC, 5:47am March 28 2017 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.JAY WINTER:

YOUR ARTICLE ON WW1 IS EXTRAORDINARY. IT RESONATED WITH MY HEART AND SOUL. THE 'RETROSPECTOSCOPE' OF TIME ALLOWS A REASONABLY CIRCUMSPECT AND OBJECTIVE REVIEW OF THAT AWFUL HOLOCAUST....SUCH A USELESS AND DESTRUCTIVE WAR!

AT YALE (1956-60) I MAJORED IN 'MODERN EUROPEAN HISTORY' AND REMEMBER SUCH DEPARTMENTAL LUMINARIES AS HOYA HOLBORN AND JOHN BLOOM. I HAVE KEPT ALIVE MY ABIDING INTEREST IN WW1, AND HAVE READ/STUDIED A DOZEN BOOKS ON VARIOUS ASPECTS OF IT.....INCLUDING BOOKS BY SURVIVING SOLDIER AND NOVELISTS.

TO PARAPHRASE MY FAVORITE AUTHOR, DOSTOYEVSKY, EVIL IS INHERENT IN THE HUMAN CHARACTER, AND NO AMOUNT OF GOVERNMENTAL, SOCIAL OR PERSONAL ENGINEERING WILL EVER ALTER THAT!

Professor Winter's incredibly thoughtful, intelligent article provides clarity , insight and a sobering message in his brilliant summation of the historical events surrounding "The Great War." I hope it is widely read and its message taken to heart . He is a masterful writer. Thank you

Professor Winter asks “is it possible to honor the men who died in war without glorifying war itself?”

For many Americans, this timeless question brings to mind Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall, both of which would seem to present an affirmative answer.

On the other hand, consider the two murals by John Singer Sargent dedicated to “The Lost Generation” of WWI and displayed on the main staircase of Harvard’s Widener Library. The murals depict a fantasy of victory that any wartime leader might wish to inculcate in the minds of young recruits (in this case, Harvard students) marching off to slaughter.

The reality of war, as described by Prof. Winter, bears no resemblance to the jingoistic super-patriotic vision presented in Sargent’s murals. One may reasonably wonder whether Sargent and Winter are describing the same War.

The contrast remains pertinent, as politicians continue to lure us, and our children, with statements unhinged from facts. Professor Winter’s article should remind us all of the importance of remaining firmly grounded in the truth.