loading

loading

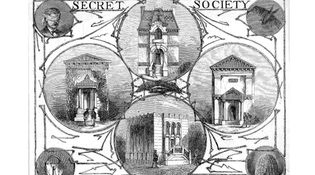

From the EditorThe evolution of secret societiesA new book looks at the history of Skull and Bones and its kin.  View full imageWhat kind of person writes an 800-page book about the rise of the secret societies of Yale College? If you’re imagining a conspiracy theorist in a basement, you couldn’t be more wrong. I know David Alan Richards ’67, ’72JD, slightly; he’s a charming, gregarious New York real estate attorney whose avocation is writing and who loves the work of Kipling. (He donated his extensive Kipling collection of first editions and personal items to Yale.) His book is also entirely different from the book you are probably imagining. Most writings about the societies are exposés, or fever dreams about murky international webs of power. Dave is a scholar, and his book, Skulls and Keys—out in early September from Pegasus—is deeply researched, carefully footnoted, and serious. The mere fact that he uses the term “senior society” is one sign of a knowledgeable writer. (The societies are senior-year clubs, sometimes secret, sometimes quite open. For years, the names of Skull and Bones inductees were routinely published in the New York Times.) Much more significantly, Dave’s mission is to document, as fully as possible, the social milieus and interactions that brought young men together in fraternal groups and ultimately created what he calls “a peculiarly American forcing chamber of self-education and prestige.” His in-depth approach is very highly detailed—hence those 800 pages—but it is also a boon to the reader, because his method is to share voices and anecdotes from the 1700s through the present day. He quotes, for instance, the first attempt to extinguish fraternities, at Union College: “The first young man who joins a secret society,” declared the president in 1832, “shall not remain in Coll[ege] one hour.” In his introductory look at the roots of the urge to form clubs, Dave goes all the way back to 1659 for an early Masonic oath: “All that we or attendees shall be[,] you keep secret, from Man, Woman, or Child, Stock or Stone.” He touches on many groups, including Yale’s literary and debating society Linonia, believed to have been founded in 1753; college societies in England; Phi Beta Kappa, founded in Virginia in 1776; and the American fraternities of the early 1800s. But his focus is on the Yale senior societies proper. He begins his deep dive at Yale in 1832, when Phi Beta Kappa retreated from its original “injunction of secrecy.” That change served as the impetus for the founding of what was then called Scull and Bone. It was followed by many others, starting with Scroll and Key in 1842. The book takes us all the way to the present, showing how major events in the country affected the microcosm of the societies—their small but influential world responding to the World Wars and the social changes of the sixties and seventies, as when the societies began gradually admitting women. There are some tragedies. We learn about literary scholar F. O. Matthiessen ’23, who jumped from the 12th floor of a Boston hotel in 1950; investigators believed that he first removed his Bones pin from his shirt, but then, “suddenly remembering that it should never leave his person, he refastened it to his shirt” before leaping to his death. But for the most part, the book is a readable account of the forces that have kept these groups active and popular—and often proliferating—through today. In his epilogue, Dave notes that a recent Yale Daily News announcement listed 47 senior societies. The president of Union College lost his fight long ago.

The comment period has expired.

|

|