loading

loading

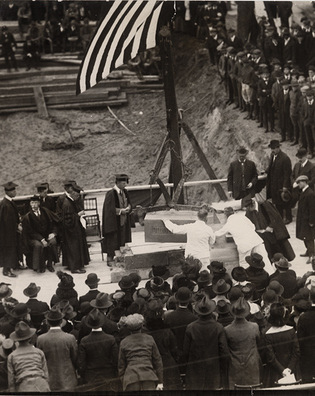

Old YaleThe Memorial Quadrangle’s beginningsIn wartime, Yale began building a new “center of beauty.” Judith Ann Schiff is chief research archivist at the Yale University Library.  Manuscripts & Archives, Yale UniversityThe cornerstone for Yale’s Memorial Quadrangle—later to become Branford and Saybrook Colleges—was laid on October 8, 1917. A time capsule inside the stone includes newspapers, course catalogues, coins, and more. View full image“The waste of war is destroying churches and castles and glorious monuments of antiquity,” said President Arthur Twining Hadley ’76 on October 8, 1917. “Unless the world builds new centers of beauty and affection to take the place of the old, the twentieth century will, in spite of material progress, be essentially poorer than the nineteenth.” Hadley was speaking at the dedication of the cornerstone for the Memorial Quadrangle, the set of dormitories that would later become Branford and Saybrook Colleges. His words helped explain why Yale was launching a monumental project at a moment when nearly all students and faculty were in military service. America had entered World War I six months earlier. The date for the dedication, 100 years ago this fall, was chosen with care: it was two centuries to the day after the start of construction of the first Yale College building in New Haven. The project was the gift of Anna M. Richardson Harkness, philanthropist and widow of Stephen V. Harkness, a partner in Standard Oil. Following the death of her son, Charles W. Harkness ’83, in 1916, she offered to build a memorial in the form of one or more quadrangles with a tower. (Charles’s brother, Edward S. Harkness ’97, who would later fund the residential college plan, represented the family on the project.) With a capacity of 600 students, the new building would accommodate the junior and senior classes who were then living on the Old Campus, freeing space for all freshmen and sophomores to live on campus for the first time in many years. In March 1917, Yale’s board of trustees accepted Mrs. Harkness’s donation. A city block adjoining the Old Campus, bounded by Elm, York, High, and Library Streets, was selected, although it required the purchase and removal of private houses and stores, as well as razing and replacing several university buildings, including the Peabody Museum. The design was entrusted to Edward Harkness’s friend and personal architect, James Gamble Rogers ’89. It was Rogers’s first work for the university, although he had already designed the New Haven Federal Courthouse and the Yale Club of New York. Rogers assembled a talented team of artists who would continue to work on elements of most of his future Yale buildings: sculptors René Chambellan and Lee Lawrie ’10BFA, iron designer Samuel Yellin, stained glass and window designer Owen Bonawit, and landscape gardener Beatrix Farrand. In addition to memorializing Charles Harkness, the new building was to honor all of Yale’s “illustrious sons” and “historic past” through its stone carvings and windows. Gateways were named for early colonial leaders leading up to the founding, courtyards for towns where it was founded and first conducted, and entries for its “distinguished graduates.” Everywhere, the ornament recalls the facts and fancies, legends, songs, and traditions of Yale. The quadrangle’s most prominent feature, the 216-foot Harkness Tower, would quickly come to serve as a symbol of the university. Described as one of the world’s tallest free-standing towers at the time, its ornament includes statues of famous Yale graduates, allegorical figures representing the arts and sciences, and representations of soldiers from American wars from the Revolution to World War I. In 1918, construction was suspended due to the war, with just the foundations completed. It recommenced in the spring of 1919, and hundreds of stonemasons and wood carvers worked to make up time, working under heated tarpaulins through the harsh winters of 1920 and 1921. The quadrangle was completed in the spring of 1921, in time for the inauguration of President James Rowland Angell. English professor Stanley T. Williams ’11, ’15PhD, paid the brand-new building the highest compliment of an institution that values tradition and continuity. “Already it is difficult to imagine Yale without the Tower and Quadrangle,” he wrote. “The Tower rises through the mist of green of the ancient campus, and is not new nor old, but Yale.”

The comment period has expired.

|

|