loading

loading

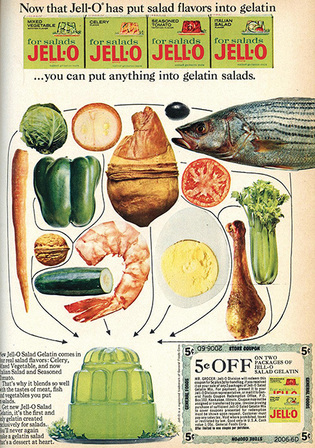

featuresHow food became chicA history professor looks at the increasing sophistication of the American palate. Paul Freedman is the Chester D. Tripp Professor of History and author of Ten Restaurants that Changed America (2016). In a 2015 Tedx Talk, Kimbal Musk, brother of Tesla cofounder Elon Musk, said, “Food is the new Internet.” The pithy comparison is plausible because of the extraordinary attention now paid to food, not just in the conventional “what’s for dinner” sense, but as the object of reviews, tourism, and social media posts. The creation of the Food Network in 1993 and its transformation from cooking information to entertainment programming is perhaps the most influential and visible aspect of the modern food surge, but only one of many.  From the October 16, 1972 issue of New York Magazine. Photo by Dan Wynn.In 1972, food writer and critic Mimi Sheraton published a piece in New York magazine about her yearlong project to try every one of the 1,961 items sold in Bloomingdale’s food shop. View full imageSome of the answer to why this is happening is summarized by the cliché that “food touches everything.” It is not only a need and a pleasure but a basic aspect of globalization, environmental problems, health issues, and how people see themselves. At Yale, the undergraduate class I teach on the History of Food and Cuisine has only a minority of history majors; many students are majoring in fields such as environmental studies, political science, and economics. But alongside this seriousness of purpose about food is a kind of lively pleasure in accumulating knowledge of and experiences related to food, which now has more mass appeal than it did in previous “gourmet” booms. True, this passionate attention is not entirely unprecedented. In 1968 the writer and social observer Nora Ephron considered herself to be living during an absurdly expansive food craze, an era when everyone started serving curry and rumaki—marinated chicken livers and water chestnuts wrapped in bacon and sprinkled with soy sauce. In 1972, the future New York Times restaurant reviewer Mimi Sheraton wrote a piece for New York magazine entitled “I Tasted Everything in Bloomingdale’s Food Shop.” She didn’t describe all 1,961 items she sampled, but she did describe in detail her favorites from the cheese and bread departments, as well as awful products of the processed gourmet-food world such as canned pheasant and cheese soufflé mix.  Jell-O ® trademark used by permission from Kraft Foods Group Brands LLCOne of the foods in vogue in the 1950s was aspic salad. It could be made at home with Jell-O gelatin and virtually any other ingredients the cook chose. View full imageToday’s food craze is not limited to New Yorkers or other self-described sophisticates. It is a widespread phenomenon that has made Nashville and Pittsburgh gastronomic destinations. There is, however, a paradox: this attention to the quality and variety of food comes at a time when relatively little cooking is going on. Say what you like about the laughable 1950s—the omnipresence of casseroles held together with cream-of-mushroom soup, aspic salads made with Jell-O gelatin, cocktail frankfurters, and Miracle Whip sandwich spread and salad dressing—people prepared meals in their own kitchens. Today more than half the money spent on food goes to things purchased outside the home, from restaurants to pizza deliveries, from take-out to drive-thru lanes. The kitchen is for hanging out and grabbing snacks. The oven is such an unfamiliar piece of equipment that NPR radio stations are deluged with calls every Thanksgiving because roasting a turkey is such a daunting project, especially when you’ve forgotten how to turn on the appliance.  Notable moments in the history of US food, left to right: Pierre Franey’s 1979 best-selling cookbook; Wonder Bread, epitome of Americans’ early love of processed food; and two fad foods, quinoa (in the 2000s)and kiwi fruit (the 1970s). View full imageThe amount of time spent preparing meals has plummeted. In 1979 Pierre Franey published The New York Times 60-Minute Gourmet, a cookbook that is among the better examples of the quest for quick, high-end dishes—a category of recipes constituting the Holy Grail of American food publishing. In contrast, the magazine Gourmet, in its final years before being shut down in 2009, featured “Ten-Minute Mains” (main courses). In answer to the dismay expressed by some that Gourmet with its title and traditions could advocate such haste, its editor, Ruth Reichl, said the public was so alienated from cooking that the important thing was to coax them into the kitchen to find out how to make food at the stove. Once they saw how easy it was, perhaps they’d chop up their own cabbage, make their own marinade, or cut up a whole pineapple.  Stockfood/AndradeView full image Stockfood/Studio R. SchmitzView full imageNevertheless, the enthusiasm for food is not only real but important, more than a blip in the endless history of fashion. This is because it’s based not on some particular new ingredient, like kiwi fruit in the 1970s or quinoa in the 2000s, but on quality, seasonality, and locality—all included under the rubric of farm-to-table. It’s easy to make fun of the sanctimonious moral earnestness behind this tendency, as in the Portlandia episode about restaurant patrons who inquire about the free-range chicken and eventually decide they need to visit the chicken to make sure of the conditions under which it is raised. Comic implications aside, the farm-to-table ethos breaks with a long-standing American tradition of food marketing, preferences, and publication that downplayed quality in favor of convenience and variety. What made the American food industry great, and along with it women’s magazines, home economists, and restaurant chains, was processed and standardized food. This is for a number of reasons, ranging from money (mashed potato mix is more profitable than just selling potatoes) to the perceived drudgery of cooking (emphasized by advertising) to the consolidation of farming and the need to transport things long distances (so produce had to be bred for durability rather than taste). By the opening of the First World War, long before the rest of the world embraced packaged foods, Americans were consumers of sliced industrially produced bread, canned fruits and vegetables, breakfast cereals from boxes, and prepared sauces and salad dressings. The compensation for what might at first seem like brand-name homogenization was to offer variety: the ice cream might come from a factory, but it was available in 28, 32, or more flavors. The Neapolitan original pizza was a simple preparation, but in the United States, it could be marketed with anchovies, pepperoni, mushrooms, and eventually pineapple. The proliferation of options was not just to keep customers interested or to create more buying opportunities; it was meant to distract attention from the bland sameness of the product. Quality is much harder to assure than variety within an industrial system, because it requires freshness, breeding for flavor, and other factors that can’t be easily scaled up or mass marketed. There’s no doubt this has changed radically in the past few decades. The food available in supermarkets and restaurants really is better than it was in the recent past, and that is a crucial motive for the contemporary enthusiasm for food writing, television, and exploration. The elegant but awful “Continental” food of restaurants in the past—what Calvin Trillin ’57 referred to as the “Maison de la Casa House” sort of place, with its huge leather-covered menus, tuxedoed waiters, thawed-out pork cutlets sold as veal scaloppini, and heavy use of margarine and canned chicken broth—is, mercifully, gone. Restaurants are driven by the preferences of chefs rather than of the maître d’hôtel at the front of the house, and so even if the atmosphere is noisier and less formal than in the past, more attention is paid to the food. Local farms, craft brewers and cheese makers, carefully raised animals—none of this is easy to provide under the traditional food-industry models, but they have become prominent because of a preference for taste over other considerations that drove American tastes and options in the past. How this happened and why has a lot to do with the food movement that began in California. As Joyce Goldstein and Dore Brown note in their book, Inside the California Food Revolution, there is more to this story than the mission of Alice Waters and her restaurant, Chez Panisse. There was a network of chefs, activists, investors, and food enthusiasts who launched and sustained an effort, beginning in the 1970s, to build a restaurant ideal based on local, seasonal, sustainable ingredients. Its mission was not just to satisfy the delicate palates of elite clients, but also to affect the way everyone, including schoolchildren, suburbanites, and people in working-class and poor communities, thought about food. What was revolutionary was not only getting rid of the stuffy atmosphere of the Maison de la Casa House, nor dethroning the hegemony of French cuisine, but the seemingly simple priority for primary ingredients of freshness and impeccable quality. Defining quality in terms of freshness and naturalness (i.e., raised on a small, non-industrial scale) seems obvious now, but, as we’ve seen, freshness and naturalness are hard to deliver. Moreover, they are often eclipsed by the allure of new ingredients or variations. If sunflower seeds or raspberry vinegar or sun-dried tomatoes were in vogue, then add them to everything. Simplicity, on the other hand, requires a painstaking, often expensive search for better-tasting products and cannot be covered over by multiplication of ingredients and flavorings.  Susan Wood/Getty ImagesAlice Waters (front row, third from left), shown here in 1982 with her kitchen staff at Chez Panisse, was an influential figure in the movement for fresh, local, high-quality ingredients. View full imageThe most significant contribution of Waters and her allies was to link better food practices to better-tasting food. Rather than merely telling people to eat more vegetables or sustainably raised seafood, they showed that these things tasted better. In place of the granola-and-seaweed ethos of the 1960s food movement—which, however ecologically conscious, failed to attract a large following—the last quarter of the twentieth century created a “delicious revolution” that emphasized both reform and taste. This could have become just another temporary fashion, but the advent of food television and the Internet made food a form of entertainment and self-expression. Social changes encouraged both attention to food and trends such as dining out rather than home cooking. More travel brought increased knowledge and an expanded sense of taste possibilities. Environmental and health concerns prompted questions about where our food comes from and its true costs. The revival of cities and the preferences of the so-called millennials for urban amenities, and their lack of interest in quickly building families, buying houses, or owning automobiles, encouraged social competition in other fields. Having a new luxury car or a large house as a mark of status has given way to interesting travel, mindfulness, wellness, and food knowledge. In the contest for prestige, unique experiences now count more than objects. Not all of this is good—you might wish your neighbors still boasted about their powerboats rather than their kids’ college admissions—but that is the trend, and it has some positive consequences for the present and future of food. If Target and Walmart switch to eggs from more-humanely treated chickens, that has an impact; if McDonald’s replaces margarine with butter to improve taste, that is an interesting sign. If the supermarket middle aisles are languishing as fresh food becomes more important, that might help with problems of health and sustainability. If the food fad is here for the long term, some things may change. The most intriguing possibility is a diminution in the preference for restaurant or other meals taken outside the home. Restaurants in cities such as Washington, DC, or San Francisco are disproportionately patronized by young people who face a contradiction between their eagerness to spend discretionary income on meals and their preoccupation with the control of their bodies and immediate environment. It may be that, sooner or later, more people will decide that cooking their own meals helps them monitor their intake of salt and sugar, or that it is a form of group activity compatible with the way the non-Pepsi generation has fun. But don’t hold your breath for it.

The comment period has expired.

|

|