loading

loading

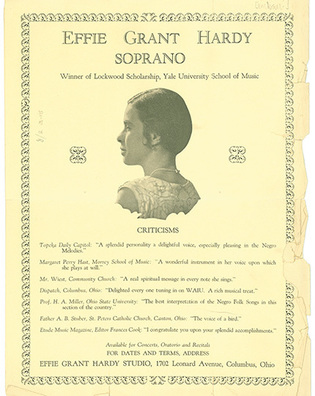

Old YaleA banner year for black studentsA talented soprano was among five African American prize winners in 1908. Judith Ann Schiff is chief research archivist at the Yale University Library.  University of Massachusetts AmherstEffie Grant Hardy, shown here in a flyer advertising her musical ability, was in the Class of 1909 at the Yale School of Music—one of the three Yale schools that accepted women at the time. View full imageA century ago, Yale was admitting an extremely small number of African Americans. But an article from that era shows that even when black students at Yale were few, their achievements were notable. “A Remarkable Showing of Negroes as Students in Yale University and in New Haven Public Schools” was the headline for a news story in the September 1908 issue of the American Missionary, a religious magazine that often discussed race. The article noted the “number of high-standing scholars” whose “erudition and application” was “truly wonderful,” especially “as so many young colored people have been taking Yale University honors and prizes this year.” Of 11 black students registered at Yale in 1908, the article reported, five had won prizes that year. They included two men in Yale College, one in the Law School, one in the Divinity School, and a woman in the School of Music (one of the three Yale schools open to women at that time, along with the School of Art and the Graduate School). William Emanuel Hendricks ’08, born in St. Croix, received the second Townsend Premium for seniors, a prize for public speaking. William Porter Norcom ’11 of New Haven won the freshman Berkeley Premium for Latin composition. Charles A. Smythwick ’08LLB of Fairfield, Connecticut, was awarded the Law School’s Parker Prize, $125 for the best thesis on a subject in Roman law. Samuel Richard Morsell ’10BDiv of Baltimore won the second Downes Prize for a Divinity junior for excellence in hymn and scripture reading. And Effie Ella Grant, Class of 1909 at the School of Music, won the Lockwood Scholarship for singing. Grant was the first known African American woman to enroll at Yale. She attended from 1906 to 1909, but, for reasons that are unclear, did not receive the Bachelor of Music degree customarily awarded after three years of study. (Helen E. Hagan, who earned the degree in 1912, is the first known African American woman to receive a Yale degree.) In 1906, Grant lived in downtown New Haven where “Mrs. C. Grant, Manageress” (perhaps her mother) operated the “Yale Employment Bureau” for housekeepers. Grant’s singing prize apparently led to performances. In April 1909, the Baltimore Afro-American publicized an upcoming recital in Brooklyn, where Grant would be on a program headed by violinist Joseph H. Douglass, grandson of Frederick Douglass. A May 1909 School of Music concert featured her performing the soprano aria from Haydn’s Creation. By 1910, Grant was teaching voice culture at Western University in Quindaro, Kansas; a historian calls it “probably the earliest black school west of the Mississippi and the best black musical training center in the Midwest . . . during the 1900s through the 1920s.” Otherwise, the biographical information in her alumni folder at Yale is sparse. By the mid-1920s she was a private teacher of music and the wife of Arthur W. Hardy, executive secretary of the “colored Y.M.C.A.” in Columbus, Ohio. Effie Grant Hardy’s daughter has stated that her mother passed away on December 28, 1983, at the age of 98, leaving two daughters, five grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren. Online databases provide more evidence of her inspirational legacy. In 1930 the New York Amsterdam News reported that “Mesdames Effie Grant Hardy and Helen Hagan Williams” would perform with others at “an all star musicale” for the benefit of the Sojourner Truth branch of the YWCA in Newark. A 1909 Afro-American news clipping, enhanced by her pensive photograph, bears silent testimony. It reads, “If Miss Grant continues she will someday rank with the world’s great musicians of any race or clime. There is a large number of young people in New Haven who have taken to music as a profession, and those whose good fortune it was to attend Miss Grant’s recital doubtless went away encouraged and inspired to stop at nothing shorter than the best possible equipment for their chosen profession.”

The comment period has expired.

|

|