loading

loading

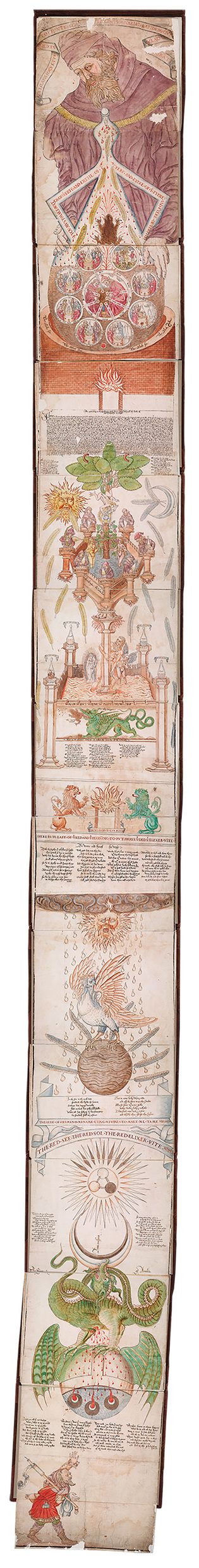

Arts & CultureThe lasting lure of alchemyObject lesson: A sixteenth-century scroll depicts the quest for eternal life. Kathryn James is the Curator of Early Modern Books and Manuscripts and the Osborn Collection at the Beinecke Library.  Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript LibraryThe nearly 30-foot-long document at left (with detail above) is one of 23 known copies of the Ripley Scroll, a fifteenth-century guide to alchemy. It can usually be found in the Beinecke, but until January 27 will be at the New-York Historical Society in Manhattan for a British Library exhibit called Harry Potter: A History of Magic. View full image Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript LibraryView full image“Here is now both white and redde / and also the stone to quicken the deade,” reads an illustrated verse of a sixteenth-century copy of an alchemical poem known as the Ripley Scroll. The “stone” is the philosopher’s stone, the source of wealth and eternal life, and the object of alchemical research through the early modern period (and all the way to the halls of J. K. Rowling’s Hogwarts). The original Ripley Scroll is attributed to George Ripley, a fifteenth-century English Augustinian friar and the author of The Compound of Alchymy, a guide to alchemical transmutation in English verse. The Ripley Scroll is also a genre. Some 23 copies of the text are known. Of these, 17 follow the sequence of images and text found in the Yale copy: an allegorical depiction of the process of alchemical transmutation that begins with the figure of a magus and ends with a pilgrim—often thought to represent George Ripley—pointing up at the text above. Along the way, the verse leads its reader through the characteristically emblematic depiction of alchemy in the early modern period, in which chemical experimentation is shown alongside the figures of Adam and Eve, the toad, the dragon, the bird of Hermes, and others, all representing stages in the alchemical process. Centuries after its creation, a Ripley Scroll was read by Carl Jung, the Swiss psychologist and erstwhile collaborator of Sigmund Freud. Jung was an avid collector of early modern alchemical works, and he drew extensively on alchemical imagery in his psychological theory. In Jung’s work, the emblematic representation of the alchemical process served as an allegory of the psyche—a representation of the internal state of mind rather than of the material world. “The experiences of the alchemists were, in a sense, my experiences,” Jung wrote in his 1965 autobiography. “When I pored over those old texts everything fell into place: the fantasy-images, the empirical material I had gathered in my practice, and the conclusions I had drawn from it.” This copy of the Ripley Scroll came to Yale because of Mary Conover Mellon, a Vassar graduate who had married Paul Mellon in 1935. In 1937, Mary and Paul Mellon heard Jung speak at the Analytical Psychology Club in Manhattan, and Mary Mellon was drawn to his ideas; she visited him at Bollingen Tower, his house in Switzerland, as war broke out. By 1945, she had established the Bollingen Foundation, which oversaw the translation and publication of Jung’s works, including his three volumes of alchemical writings. She also collected Renaissance and early modern alchemical works, including those Jung had owned and drawn on for his theories. After Mary Mellon died, in 1946, Paul continued to build her collection and to support the Bollingen Foundation. In 1965, he donated the Paul and Mary Mellon Collection of Alchemy and the Occult to Yale.

The comment period has expired.

|

|