loading

loading

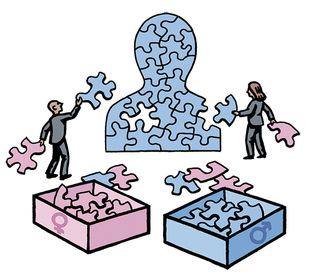

FindingsWhen the middleman is the problemPeople are prone to acting on other people's biases.  Gregory NemecView full imageSuppose you’re running a business, and you have a job to fill in one department and a good candidate for it. But the candidate is a woman—and the department is headed by a misogynist. What would you do? Many people in that position, a Yale study has found, would hire a man instead. “We did not think it would be so easy to get people to accommodate others’ prejudices—and it turns out it is,” says Andrea Vial ’18PhD. Vial was the lead author on the study, in which a group of volunteers answered hypothetical questions about hiring decisions. (She is now a postdoc at New York University.) Vial and her colleagues found that the “gatekeepers” they surveyed were reluctant to bring a person into the organization who they thought would be subject to bias. This was the case with both men and women gatekeepers, and it was the case even with those who carried little or no gender bias themselves. The effect, Vial adds, was not subtle. The gatekeepers wanted not only to head off interpersonal conflicts, but also to ensure that the organization would run smoothly. “It all boils down to this idea of doing your job,” Vial says. Many gatekeepers felt guilty about their choices. But they still chose to act on other people’s biases. (The study was published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.) The research suggests that the roles people play at work “can have a very, very powerful influence on their behavior—beyond, sometimes, other types of factors that might motivate their behavior, like their social identity or their beliefs,” Vial says. If a job “puts you in this situation of having to make this decision, more often than not, people will go ahead and discriminate.”

The comment period has expired.

|

|