loading

loading

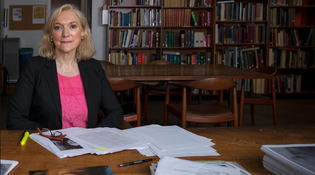

From the EditorFrom Chile to the RenaissanceAn immigrant alumna's path to success.  Courtesy Vilcek FoundationCarmen Bambach ’81, ’88PhD, solved a puzzle about Michelangelo as an undergrad; she now curates drawings and prints at the Met. View full imageNever underestimate a soft-spoken young woman. She may possess superpowers. Carmen Bambach ’81, ’88PhD, was a Berkeley College classmate of mine. I didn’t know her well, but she was friendly and loved a laugh; she was a Feb Club regular; she once dressed as the devil for Halloween. She had an accent. I was vaguely aware she’d immigrated from Chile. In January, she won the inaugural Vilcek Prize for Excellence, a $100,000 award honoring an immigrant who has made a significant impact on “American society and world culture.” Why Carmen? I’ve learned a lot more about her than I knew in college, and it’s quite a story. Carmen was 14 when her mother and father took her, her sister, and her two brothers out of the country. Augusto Pinochet had assumed control over Chile in a coup. It was a military regime, with no freedom of speech, and the Bambachs could no longer bear their own government. Sometimes there were bodies lying on the ground outside their gate. And her parents wanted to give their children the best education—and values—possible. The Bambachs settled in Greenwich, which at the time, Carmen says, was a sleepy little town. She spoke German and Spanish but not English, and the transition into American high school was rough. She still remembers people talking to her loudly, as if it would somehow make them more understandable. But Yale was different. “I feel Yale had everything to do about my intellectual and professional life,” she says. She was “not the most lucid writer” in English when she arrived, but she found mentors in her chosen field of Renaissance art history who believed in her. She credits especially the late Creighton Gilbert, as well as Judith Colton and the late George Hersey. Carmen never seems to talk about her own part in her educational growth. But her friends Robert Johnson ’81 and Tom Whalen ’81, who’ve known her well for years, say her drive to learn is astounding. In her senior year, she also showed she had a gift. She was reading an art history book and saw an odd, rather inscrutable drawing by Michelangelo that had been deemed to be an armpit. She perceived something different: turning the book upside down, she saw a full-sized sketch for the head of Haman, one of the figures in the Sistine Chapel. In 1983, with Gilbert’s support, she published an article in the Art Bulletin. A novel hypothesis by a young woman barely out of college was, of course, suspect. But the Sistine frescoes were being cleaned, and the late Fabrizio Mancinelli—director of the scientific research and cleaning team—believed her. In 1990, with an assembly of art historians watching, they climbed together onto the scaffolding underneath the Punishment of Haman. She placed a transparency of the drawing against the fresco. “It fit the head of Haman perfectly,” she wrote me. Today, Carmen is the curator of drawings and prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the author of dozens of articles and many books. She’s a widely known expert on Renaissance art. Her Met bio lists some dozen fellowships and scholarships, including the Rome Prize. When I spoke with her, Carmen had just shipped her magnum opus to the press: a four-volume biography of Leonardo da Vinci that seeks to understand his work in the context of the life he lived. She’s been working on it for nearly 24 years. She has a particular interest in the steps he took—deliberately and with care, she says—to grow and develop himself as an author and artist. It’s a subject that Carmen, of all people, would understand.

The comment period has expired.

|

|