loading

loading

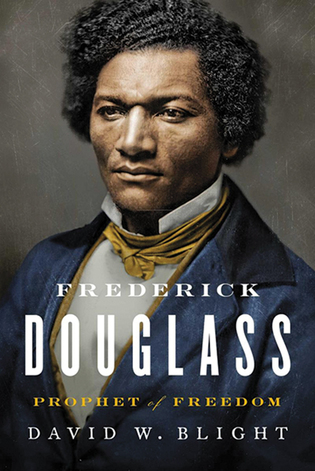

Arts & CultureReviews: March/April 2019Imani Perry reviews David Blight's biography of Frederick Douglass; an alumna's novel about a marriage gone wrong.  View full imageFrederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom Imani Perry ’94 is the Hughes-Rogers Professor of African American Studies at Princeton. Her most recent book is Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry. David W. Blight’s most recent book is a stunning display of his dual callings as a scholar and a master of the craft of writing. Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom is the most comprehensive biography to date of Douglass, a man born into slavery who became one of the most famous figures of the nineteenth century: a brilliant intellect, a master orator, and an abolitionist turned statesman. Douglass’s life is a veritable story of the growing pains of the American nation, from bondage to freedom to racial caste. Last year at a dinner I sat next to Professor Blight, who is the director of Yale’s Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition. Genial and soft-spoken, he possesses classic professorial form—probing and thoughtful in an earnest and disarming way. Such care with ideas and words is put to superb effect in this book. Of course, Douglass is a singular figure. He was a self-proclaimed self-made man, who freed himself and claimed that freed self as a symbol and argument, at first for abolitionist virtue and later for Black citizenship. But under Blight’s careful examination, Douglass’s self-fashioning is situated in a series of complex relationships over the course of his lifetime. Early wounds, caused by the ruptures of intimacy wrought by slavery, haunted Douglass to the end. Still, in slavery and as a freeman, he continuously built relationships. Some were with world-historical figures. Blight offers sensitive accounts of Douglass’s close but conflicted relationships with William Lloyd Garrison, John Brown, and Abraham Lincoln. With each, Blight shows, there was a mutual sincere regard, and each man’s greatness and deep fallibility, Douglass’s included, are revealed. Other forms of companionship disclose Douglass’s progressiveness, and limitations, when it came to gender. Although he was a man who believed in the rights of women, Douglass was dismissive of and frustrated by his wife and the mother of his children. Anna Murray Douglass, a freeborn Black woman, remained largely illiterate and homebound as her husband built his peripatetic career as an abolitionist. And that home was encroached upon by two of Douglass’s intellectual peers, white women friends, who treated Anna dismissively if not cruelly. Though Anna’s interior life is left unwritten, Blight tenderly speculates about her from circumstance and her rituals of care for her family. Among the most fascinating relationships are those Douglass maintained with less well-known yet comparably remarkable African American social and political activists of his generation. In that community he found companionship as well as bitter competition. In Blight’s telling, a nuanced picture of nineteenth-century Black political thought emerges. Robust debates over colonization, constitutionalism, armed self-defense, insurgency, and nationalism were sustained through the press and political associations. Douglass, though the most famous, was not always right nor the most sophisticated about these matters. Indeed, his diplomatic assignments in Santo Domingo and Haiti posed serious challenges to his ethics and political commitments. His preciously held, and valiantly fought for, American citizenship put him on the side of empire, an empire that threatened to encroach on his fellow former bondspeople in the Caribbean. Douglass struggled with the racial politics of the American empire in its foreign policy, and at the same time fought against the cruelly refreshed racial hierarchy of the post-Reconstruction United States. Throughout, Douglass was beset by personal difficulties and often tragedies. He was a man burdened with a large family, and sometimes an entire race, relying upon him. He faltered and grieved. He fell out of favor at times—perhaps most dramatically with his second marriage, to a much younger white woman. And yet Douglass persisted, laboring where he knew he belonged: in the thicket of a country reorganizing itself after a deadly war and constantly at risk of failing yet again to meet its promise of liberty. For that purpose, Douglass labored beyond reason to the bitter end. blight’s narrative is lively and engaging. It is also a magisterial management of time and history. The three narratives Douglass wrote of his own life are primary sources. Blight draws upon them to narrate Douglass’s life, and yet also narrates the composition of the narratives themselves: how they changed and grew as their author did. Likewise, Blight’s vast knowledge of the various bodies of Douglass scholarship—literary, religious, and jurisprudential, along with the historiographical archive—facilitates his crafting of a story that moves and reveals as well as tells and demonstrates. The kinetic, dynamic, haunted life of Douglass that Blight gives us is only possible through another type of haunting, one that is both beautiful and deliberate. Prophet of Freedom is the product of the 40 years Blight has spent with the life of Douglass, from dissertation to magnum opus. Blight’s book is a testament to the value of a long-term intellectual commitment. Even better for us, it stands as a commitment not only to knowledge but also to something both dearly held yet too often fleeting and fragile: the American ideal of freedom.

|

|