loading

loading

featuresThe alchemist of costumingJane Greenwood, Broadway's most prolific designer, turns cloth into character.  Mark OstowJane Greenwood. View full imageJane Greenwood was six when she was sent from Liverpool to the English countryside to escape the Blitz. Her mother stayed in Liverpool to manage a pub, and her father joined the Royal Tank Regiment in Africa. Since wartime economy was strict, Jane’s mother cut up one of her own dresses to sew one for her daughter. The fabric was pink Shantung silk with white spots. Jane tried on the dress and told her mother, “These spots are too big.” Greenwood grew up to be a costume designer. With 135 Broadway credits, she is the most prolific designer of any kind—costumes, lighting, or sets—in Broadway history. She has also designed for the Metropolitan Opera, the Alvin Ailey dance company, and a cult-classic movie called Can’t Stop the Music, to name just a few. She has dressed actors and actresses from Katharine Hepburn and Jason Robards to Scarlett Johansson and Ben Stiller. She’s been nominated for numerous Tony Awards and inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame, and, in 2014, she received the prestigious Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement, shared by the likes of Marlene Dietrich, Stephen Sondheim, and James Earl Jones. In the years since young Jane Greenwood assessed her new frock, she has cast her critical eye on many more silks and a great deal of gabardine, velvet, and brocade. But her life in the arts requires much more than judging fabrics. She must scrutinize every script or libretto to understand the characters’ hearts and souls (and to count how many outfits they’ll need before the curtain falls). She spends hours paging through works like Medieval Garments Reconstructed and Victorian Party Dresses, because research is the first step in bringing a costume from sketchpad to stage. She calls it detective work: “What is the essence of the period?” she asks, again and again. Her work requires knowledge of politics, social class, and design history; an anthropologist’s eye for how humans wear their clothes; literary insight; physical stamina; and the negotiation skills to collaborate with drapers, directors, and actors. At age 84, Greenwood is simultaneously impish and regal, with a pixie haircut and arresting blue eyes. She persists in the work with a zest she attributes partly to regular morning workouts. “Costume design is not for sissies,” she says. “You have to be very resilient, because everybody knows better than you do. And you’ve got to be very strong, because it doesn’t matter how many assistants you have—there’s always a morning when you’re in the subway with two bags and a hatbox.”

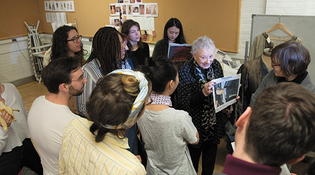

Every Wednesday for the past 42 years, Greenwood has taken Metro-North from Grand Central to New Haven to teach her costume design class. She’s done so even when it means she’ll miss the first, and crucial, dress rehearsal of a new production—as she did one morning last spring, when she walked into the costume classroom at 149 York Street carrying her leather Coach tote (black with blue shooting stars) and wearing her two trademark silver bracelets on her left wrist. Joining a dozen students at a large table, she began class as usual, by unfolding a sheaf of pages from recent newspapers, each with an image that had caught her eye. On this day she held up a photo of Cynthia Nixon wearing a Greenwood costume for the 2017 Broadway revival of The Little Foxes. Then everyone was on their feet, and Greenwood walked around the classroom, assessing the costume designs for Les Liaisons Dangereuses that the students had pinned up on the walls. Next to their own drawings, the students had tacked up their research—images from late-eighteenth-century France, the era of Liaisons. High fashion at the time, Greenwood said, was “panniers to the nth degree.” (Panniers are wide flattened hoops, worn beneath a dress to extend the skirt to both sides.) A few years later, she added, “the French Revolution comes”—she clapped her hands—“and everything goes away. They’re running around the streets in their nightgowns! Then, during the Restoration, the clothing is becoming realistic, functional. A middle class is developing.” Attention to panniers serves Greenwood’s design credo, which she repeats often: Find the right silhouette. Silhouettes change from one period to the next. “Sometimes the human shape is very much revealed; sometimes you have to look very hard to see if it’s a person.” She likes to quote one of her teachers, Scottish designer Norah Waugh: “You have to have the right cake before you worry about the icing.” Greenwood will point to a student’s drawing and comment, “You’ve done a lot of icing. Is the cake right?” Still, the details are critical. While reviewing one student’s work, Greenwood placed her hand beside a sketch of Madame de Rosemonde, a sympathetic character among the many scoundrels in Liaisons. Characteristically, she both complimented and corrected. “This is almost terrific,” she said. “The underskirt is a bit long. You need to see the shoes.” For every play, opera, or ballet her students design, Greenwood spends much of the first class showing slides—primary-source depictions of clothing from the era. For Antony and Cleopatra, the students examined Egyptian tombs. For The Lion in Winter, they looked at twelfth-century stone effigies of fallen Crusaders (excellent for understanding the construction of trunk hose and doublets). Before dressing the Tudors in A Man for All Seasons, they studied Hans Holbein portraits of Henry VIII and his court. “It was a time of potboiling unrest,” Greenwood told her class. “Notice how somber everyone looks. There’s no smiling for the selfie here!” Students do most of their research online, perusing museum slide shows or Pinterest pages like “Eighteenth Century Art—Lads.” Greenwood prefers books. She passes around her tattered Dover Costumes of the Greeks and Romans (price $2). She recommends The Book of Costume by Millia Davenport: “Trust me. Millia Davenport can solve a lot of your problems.” And research is contemporary, too. “I can’t emphasize enough that you always have a sketchbook, or a camera, or your iPhone, and every time you see something that catches your eye, take the photo. Or do a little drawing,” she said. “Get used to being always aware of what you see. Develop the muscle of your eye.” Michael Yeargan ’72MFA, a Tony Award–winning set designer and cochair of the drama school’s design department, says Greenwood has transformed the lives of design students. Until she began teaching at Yale, in 1976, they worked alone in their apartments. She insisted that the school provide an on-campus studio where costume, set, and lighting design students could work side by side. “The students began feeding off each other. It increased camaraderie, and it reduced professional jealousy,” says Yeargan. “It changed everything.”

Mark OstowEvery Wednesday for 42 years, Greenwood has taught “the next generation” of costume designers: she takes Metro-North to New Haven to teach Yale School of Drama students the art of costuming. View full image Mark OstowStudents’ sketches for Les Liaisons Dangereuses. View full imageThe research Greenwood requires of her students and herself is only the beginning of the process. “You can’t design,” she says, “unless you really know who the people are, what the piece is about, and what the concept for the piece is.” Designers must absorb the details of the script, listen to the music, and visualize how performers will move on the stage. Greenwood looks for commentary on a play or reads the novel on which it’s based. Then she talks to the director and, if possible, the playwright, about how each of them understands the story. Before taking on Mother of the Maid, a play by Jane Anderson that premiered in 2018 at New York City’s Public Theater, Greenwood discussed the production over dinner with the director, the set designer, and lead actress Glenn Close. Greenwood mostly listened. “In the first set of meetings with directors and producers, I let them do the talking.” She is always curious about a director’s approach. “Does he want to stick with the period, or update it? Or”—puckishly—“does he want to do something on ice?” Once Greenwood has sketched the clothes, negotiations follow. She promotes her vision to the director, the costume shop, and the actors, “with iron hand in velvet glove.” The right tactics help. In a meeting with a director or a draper, as Greenwood tells her students, a drawing with “juice” will carry the day. “You can talk and talk the leg off a cast-iron donkey. But if you can make a wonderful picture, it leaps off the page. They get it!” Set designer John Lee Beatty has often seen Greenwood tango with disgruntled actors. (One of them announced from center stage during rehearsal that he hated his costume.) Thanks to Greenwood’s persuasive powers, says Beatty, “oddly, somehow that costume may change a bit, but it stays on that body. That’s an interesting psychological and tactical journey, and a service to the director, the playwright, and the production—and to that actor.” Sometimes, Greenwood herself initiates the changes. “Very often, you start off with an idea of what you think the character should be,” she says, “but then when you have the actress in the dress, you begin to see how that character’s going to develop with that particular person. I think it’s very important to go with the flow.” Once, among the guests at a jampacked Greenwood Christmas party, Beatty was surprised to see an actress whom he described as “notoriously difficult to dress.” When he crossed paths with his host, Beatty remembers saying, “‘Jane, So-and-So is in your living room. You told me she was the most difficult person to dress. Why is she at your party?’ and Jane said, ‘Oh—well, she’s one of my very best friends.’ Jane does not confuse an actress’s anxiety with her true soul, which is a very sweet quality.” “For Jane,” says Greenwood’s former teaching assistant, Cole McCarty ’18MFA, “it’s not just a love of clothes, it’s a love of people. Working with her for the last three years has reminded me that the best thing you can do is to stay engaged. She is a true blessing to everyone who knows her.”

Jane GreenwoodGreenwood’s sketches for the 2017 revival of George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan (this image and below). She believes strongly in period authenticity, but in this case, the red dress needed a zipper. View full image Jane GreenwoodView full imageGreenwood met her late husband, the set designer Ben Edwards, because his apartment building caught fire. It was 1963. They were both living on 20th Street in Manhattan, and a mutual friend brought Edwards to Greenwood’s place to wait out the blaze. Since Greenwood was leaving soon for some work at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, she invited Edwards to use her apartment as a studio until she returned. He accepted. While she was away, he sent her a stream of notes on advertising postcards he’d picked up from the funeral parlor downstairs. Edwards was already a prominent designer and a producer, and that same year he hired Greenwood to do the costumes for her first Broadway show: the debut of Edward Albee’s Ballad of the Sad Café. A year later, John Gielgud invited the two of them to work on a production of Hamlet—a smash hit for which Greenwood dressed Richard Burton and fellow players in 1960s clothing. In a break during rehearsal, as a favor to Burton, Greenwood measured Elizabeth Taylor for the canary-yellow dress she would wear when she wed Burton (for the first time), three weeks before opening night. Beatty knew Greenwood’s husband, an Alabamian who died nearly 20 years ago, at 82. “Ben was a Southern gentleman; he could wear a white suit with the best of them,” he says. Like Greenwood, Edwards cared about even the subtlest element of a design. “They were quite the team.” Greenwood still lives (with her dachshund, Dallas) in the brownstone in Chelsea that she and Edwards bought together. The couple raised their two daughters there. Sarah works as a costume designer in film, Kate as a costume and wardrobe supervisor. The Edwards sisters teamed up for the 2018 movie Ocean’s 8, orchestrating an extravagant faux Met Gala with 300 guests, all in haute couture. “It was a major undertaking,” Greenwood says. “I was proud of them.”

Mark OstowGreenwood has her students do extensive research on the era they are trying to capture. Above, the class discusses French aristocratic fashion in the era of Les Liaisons Dangereuses. View full imageIt’s a measure of Jane Greenwood’s devotion to authenticity that she is fascinated by the Bayeux Tapestry, an eleventh-century work of embroidery depicting the Norman conquest of Britain in 1066. Its 230 feet of linen can serve as a guide to medieval costume. “It stops you from wanting to be too ditzy,” she says. “It’s very simple, very straightforward.” The images can help a twenty-first-century designer “imagine the life they lived, without penicillin, a dentist.” Every year, Greenwood takes her students to tour Eric Winterling’s New York City costume shop, which produces many of the clothes she designs. “We fit each other like gloves in the way we work,” Greenwood says. “I love him.” He shares her delight in research and authenticity. They worked together to choose exactly the right “day dress” for Cynthia Nixon in The Little Foxes, set in 1900. Winterling’s shop sewed it in celadon silk brocade. “Jane wants real clothes,” Winterling says. “She doesn’t want costumes.” Even so, pragmatism sometimes wins out. Winterling struggled to construct Joan of Arc’s childhood dress for a 2017 revival of George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan. To be true to the fifteenth century, the red linen dress should have laced up like a corset. But Winterling knew that the actress playing Joan couldn’t get the dress off fast enough to reappear in chain mail moments later. He resorted to a hidden zipper. Winterling didn’t worry that the audience might notice, he says. “It’s more important that Jane doesn’t see the zipper!” Another close partner in Greenwood’s work is her associate, Daniel Urlie ’02MFA. “I spend more time with him than I do with anybody,” she says. They complement one another: Greenwood is gregarious, Urlie reserved. Like Greenwood, he is meticulous. But occasionally pragmatism rules: “Sometimes, especially if it’s crunch time, you just have to get things done,” he says. “At the end of the day, you’ve got to have clothes on bodies.” Achieving authenticity isn’t always as complicated as it was for Joan of Arc’s dress. At a rehearsal for Bright Star, a Steve Martin–Edie Brickell musical set in 1920s and 1940s North Carolina, Greenwood noticed a problem: “Mr. Murphy’s hat looks too urban,” she told an assistant. “He doesn’t look like an old codger from the country.” During a break, they settled on a black wool fedora with a blue ribbon. It was too large, but Stephen Bogardus (playing Mr. Murphy) solved the problem: “Can we just tuck a sponge in there?” he asked. Greenwood handed the hat to the assistant, with a final instruction: “You’ll have to beat this up a bit.” Mr. Murphy’s daughter, Alice, is the musical’s main character. Greenwood found a bra from the 1940s for Alice to wear—even though the audience would never see it. Its purpose, said Bright Star director Walter Bobbie, was simply to help actress Carmen Cusack play her role. When an actor’s costume has that depth of integrity, he said, “You feel like you’ve put on your clothes from a different period, not like you’ve put on a costume.” Bobbie is an actor as well as a director. He played the Bishop of Beauvais in Saint Joan; Greenwood dressed him in a heavy red wool cassock, covered with a cape that barely grazed the floor. To the audience, the bishop appeared to float, his cape fluttering as he walked. “I don’t think it’s natural to walk around in a floor-length cape,” Bobbie says. “But my character does. I haven’t moved that way before or since.” When Cherry Jones played Catherine Sloper in the 1995 Broadway production of The Heiress, she too found that Greenwood’s costuming helped her to embody her character. The story takes place in the early 1850s, when, as Jones explains, women who had been wearing “mounds of petticoats” were beginning to favor hoop skirts. Greenwood asked Jones which style fit her conception of Catherine—“it was very dear of her to even include me in the conversation,” says Jones—and they agreed that hoops didn’t suit. Greenwood flew to London to buy reproductions of Victorian-era silk for the gown Jones wore in the final act. “The petticoats were heavy, but the dress weighed maybe two ounces,” Jones recalls. “The silk would become almost lighter than air as I sat down, and it would slowly fall into place around me. I learned from my association with Jane and from my movement teacher, Jewel Walker, that even a costume deserves a complete moment. Before I would speak, I would let the costume slowly sink around me.” And throughout, “the layers of petticoats and the silk on top of it created this languid, romantic feeling.” Jones says she developed a “schoolgirl crush” on Greenwood. “I know she’s getting older like we all are, but the spirit and the fire and the charisma do not change. And there’s no bullshit about Jane. She’s straight like an arrow about what she thinks and feels, and it’s just a delicious, delightful combination.” Greenwood is currently working on the costumes for Arthur Miller’s All My Sons, starring Annette Bening and Tracy Letts and opening on Broadway in April. She has no plans to stop designing. But she has decided to retire from teaching after the spring 2019 semester. “I’ve been teaching the next generation for about 40 years,” she jokes. She reached another milestone not too long ago. Despite her Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement, and despite being nominated repeatedly for the Tony for Best Costume Design—the first nomination came in 1965—Greenwood had never won the award for an individual production. But on June 11, 2017, she won the Tony for her work on The Little Foxes. “It’s been my dream to win this Tony . . . and here it is,” she told the awards audience at Radio City Music Hall that night. She paused as people began to clap. She raised both hands, and the audience quieted. Speaking slowly and deliberately, her voice breaking slightly, she said: “Twenty-one nominations.” And with Greenwood still standing onstage, 6,000 people rose to their feet and applauded her.

The comment period has expired.

|

|