loading

loading

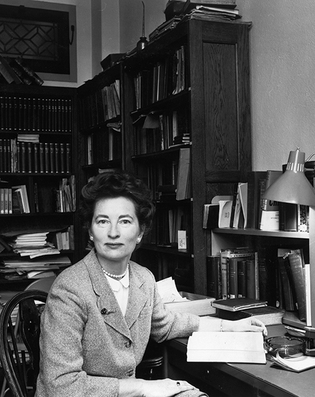

features"What she was born to do"Scholar, teacher, writer: Marie Borroff 1923-2019  Manuscripts and ArchivesMarie Borroff at her desk, circa 1965. On the following pages, eight friends and colleagues of Borroff’s share their memories of her, from her penchant for writing limericks to her deft ability to bolster a young faculty member’s confidence. View full imageIt’s been a long time since I was a Yale student, and by now I remember my teachers mostly in a few signature moments. Harry Wasserman, joking about the organic chemistry of the margarita. Michael Ferber on the isolating grief of Leopold and Molly Bloom. Alice Miskimin, reading The Waste Land aloud, sounding as if she’d been there and had heard the characters speaking. There were many others, but the professor I remember most clearly and at greatest length is Marie Borroff ’56PhD. She projected easily and confidently in the Linsly-Chittenden lecture hall, and, unlike some other famous lecturers, she didn’t grandstand. She opened up the puzzles of Marianne Moore, Wallace Stevens, and many others congenially; it was as if we students were all having a conversation over lunch with a friend who happened to be a supreme interpreter of English poetry. And she was unforgettable. By the end of the talk she would have exposed a poem’s heart—its anguish, ecstasy, fury, or even frivolity. I can still feel how her lectures moved me. She also talked about the personalities involved. She probed both the beauties and the idiocies of Yeats—coming down in the end on the positive side, with a quote from Auden’s memorial poem: “You were silly like the rest of us; your gift survived it all.” She was thoughtful about the Plath-Hughes marital cataclysm, gently urging us not to rush to judgment. And she ended every semester of her Modern Poetry lectures by reading a few of her own best poems. Our class gave her a loud, enthusiastic, extended ovation. I have a feeling that was the norm. Marie Borroff (1923–2019) was the first female professor to be named a Sterling Professor, Yale’s highest faculty honor. She was the first Yale-educated woman tenured at Yale. She published a major scholarly book at the age of 88. There were many other such milestones. She was a trailblazer, and exceptional. She died on July 5. For this issue of the Yale Alumni Magazine, which is dedicated to trailblazing Yale women, we asked several of Marie’s colleagues and friends to share their memories of her. Their stories are on the following pages. — Kathrin Day Lassila ’81

View full imageProdigy, poet, pianist, sailorPenelope Laurans

Although Marie Borroff did not become a concert pianist, as her mother (and her grandmother) might have hoped, or a professor of music as her sister became, music was nevertheless her signal gift—the music of language. As a philologist, historian of language, medieval scholar, critic, translator, and poet, her focus was on words: the way that etymology, prosody, syntax, and style in general contribute to meaning. Her translation of the late-fourteenth-century Gawain poet melds accuracy with the daunting original rhyme and alliteration schemes of the poems, preserving their music. Her criticism often focuses on the formal aspects of poems that shape the whole. Her own poetry shows the relish she took in the texture and sound of words. Throughout her life, Marie was recognized as special. The yearbook from her high school graduation at 15 from the Friends Seminary School in New York calls her a scholarly “prodigy.” At the University of Chicago, where she received her undergraduate degree, she had the approbation and regard of the formidable critics E. S. Crane and Elder Olson. At Yale during her PhD years, she won the high regard of the philologist Helge Kökeritz, the Anglo-Saxon scholar John Pope, and the medievalist E. Talbot Donaldson, who became her mentors, helped bring her back to Yale when she was teaching at Smith, and were crucial voices in her tenuring. She also won the admiration, respect, and love of another distinguished Chicago teacher, Norman Maclean, who extended his lifelong gratitude to her in the afterword of his American classic, A River Runs Through It. There he acknowledged, “I have published practically nothing that has not profited from the criticisms . . . of Marie Borroff.” She urged him, he noted, “not to concentrate so much on the story that I would fail to express a little love I have of the earth as it goes by.” In her career at Yale, her distinctiveness continued. She was the first in so much: one of the first two women tenured in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences; the first woman granted tenure in English; the first female Sterling Professor; the first woman faculty member to have a professorial chair endowed in her name; the first woman on countless committees; the first of any gender to be named a liaison to a presidential search committee. She recognized that her position allowed some older English faculty to rest easy by saying “You see, we have tenured a woman,” and although politics was not in her nature, she took that on, cared tremendously, and tried to help, even when the early odds against her were heavy. She understood she was different because, when more women began to teach in the ’70s, she was in a field that was more empirical than theoretical at a moment when the theoretical was at the heart of literary study. She was unmarried (albeit with many unrecognized personal responsibilities) and had no children. She understood she was more like the old-world women scholars who had sometimes managed to come to the fore despite all that was against them. Nevertheless, she took the side of young assistant professors, encouraged us, befriended us, had us to dinner, mentored us, fought for us when we did not even know it, and stood as a partisan in almost every committee that looked at the position of women on the faculty and in the university. No doubt the best thing she did for women, however, was simply to set herself in the middle of an all-male world as a person of the highest accomplishment, never faltering, never compromising, never making anything of her solitary position, and demonstrating by her unwavering excellence that she belonged.

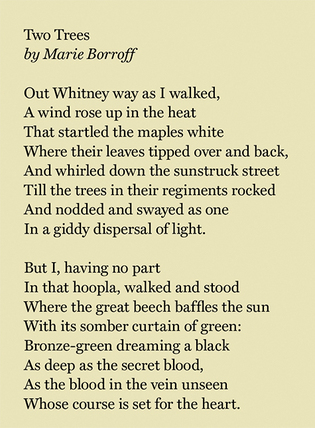

In her Yale 2006 graduate convocation talk to new graduate students, Marie’s theme was “Do the work that only you can do.” That is in fact what she did, preserving an inner sureness of her gifts that did not betray her and winning accolades for her distinctive contributions. As the world of criticism swirled and evolved around her, her scholarly standing never faltered, her classes, not only in modern poetry but also in History of the Language, were always full—and what is more, she had confidence and satisfaction in realizing her own gifts. She was asked many times to leave Yale for professorships or high administrative posts elsewhere. On one early occasion at Yale, when offered the presidency of a women’s college, a close friend told her to approach the English department chair with her new book, CV, and offer in hand. “Above all,” the friend warned, “do not smile.” Within days she had tenure. She understood that scholarship, teaching, and writing were what she was born to do and she did that, never trying to do or be something she was not, whatever the lure. Marie wore her learning lightly. Love of the earth, as she described it to Maclean, was something that was a deep part of her. She was devoted to her summers in Boothbay Harbor, Maine, where she hiked, swam, gardened, and sailed. Although she had not become a professional musician, music never left her life, and as an accomplished pianist she could play Liszt’s difficult Soirées de Vienne after an evening party, having mastered every difficult run and arpeggio. She wrote songs, produced reams of occasional light verse for every kind of celebration, was a cartoonist of wit and achievement, and—as a first-rate sight reader—would put together song sheets for after-dinner entertainments. My 40 years of letters from her summers in Maine are packed with drafts of new essays and poems, recountings of outings, updates on music, evenings with friends—and “love of the earth as it goes by.” Wallace Stevens, whose poetry was always a part of Marie’s scholarship, teaching, and appreciation, has this line in “Esthetique du Mal”: “The gaiety of language is our seigneur.” Language was indeed Marie’s seigneur, and gaiety is the right word to apply to the pleasure she took in it and the illumination she brought to it. In a year that honors the admission of women into Yale College and Yale University, Yale can take pride in the accomplishment, stature, and contributions of the faculty member who held so many firsts.

Penelope LauransRuth Yeazell (left) and Marie Borroff, deep in conversation. Both received their doctorates at Yale, and both became Sterling Professors—Yale’s highest honor for faculty. View full imageA challengeRuth Yeazell ’71PhD

I first arrived at Yale as a graduate student in English in the fall of 1967, when Marie Borroff was already a tenured professor. She was never my instructor in a formal sense. Yet she still managed to teach me, and I like to think that the lesson stuck. I also like to think that it was a lesson deeply characteristic of Marie. I wrote my dissertation on the late style of Henry James with a distinguished faculty member of those years, Martin Price ’50PhD. Then as now, Yale followed the distinctive practice of requiring that three faculty members read and report on all dissertations submitted for a degree, a requirement that the English department has long approached with great seriousness. In those days, the department also adhered to a rule that none of the readers could be directly involved with the dissertation. In my case, that meant an Americanist, a critic of the novel—and Marie. Though she might seem a startling choice, especially at a time of heightened specialization, I’ve always assumed that Marie was being asked to comment as a critic of style, having published her first book on the style of a great medieval poem, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. And comment on style she did, though perhaps not quite in the way the Director of Graduate Studies had expected. What Marie chose to address was not so much the intricacies of James’s prose as the deficiencies of mine, including my habit of repeatedly falling back on the same formulas and my excessive deference to published authorities. “Overly cautious and tentative,” she concluded, I was a critic who had “yet to find herself.” It was a challenging verdict, and I can’t pretend I immediately responded with gratitude. But when I eventually sat down to transform the dissertation into a book, it was Marie’s voice that kept me rewriting from start to finish, as I struggled to elicit my own. I don’t think I actually heard her speak until several decades later—most memorably, when she read aloud from her eloquent translation of the Gawain poet at the Whitney Humanities Center after her retirement—but I’ve been hearing her in my head my entire career.

View full imageFirst word: “budick”Beatrice Bartlett

Marie was my neighbor and friend for 35 years. It is said that at Marie’s birth, her mother cried out, “Is it normal?” “Normal” is hardly a description of Marie, who was super-talented, fun-loving, and generous. Most people saw and admired only one or two sides of her. Many do not know that she could draw accurate caricatures, do English country dancing, and play five different levels of recorders, for instance. Late in life she developed an interest in astronomy and would go out at 3:00 in the morning to witness a special configuration that she had read about. She even gamely tried my favorite sport—hiking—and together we made a few ascents. A walk in the woods revealed her ability to identify bird songs and wildflowers. Moreover, Marie’s mother had been a musical prodigy. Very early she trained her two daughters at the piano. Marie’s first word was “budick,” meaning music. The younger sister made music her career; Marie considered and rejected this during a year spent at a conservatory, but she continued to practice, learn new pieces, and compose. Marie and I made three trips as lecturers on Yale Alumni trips—one to Japan, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, one to Beijing and Xian and then up the Yangzi from Wuhan to Chongqing, and one to Southeast Asia ending in Singapore. On one of these Marie read haiku to the enthralled audience, many of whose members then responded by composing their own poems and slipping them under the door for her to admire.

Light verseThomas Appelquist

I came to know Marie and admire her greatly during the 1992–93 academic year. I had been asked to serve as one of four faculty members on a trustee/faculty search committee to advise the Corporation on the selection of the next Yale president. Marie was appointed to a special role as Faculty Counselor to the committee. It was an inspired choice. She brought her wisdom and light touch to all the deliberations, and her many interviews across the Yale community, on and off the record, illuminated every discussion of the committee. As the search was wrapping up, Marie surprised us all by composing a light poem about the process and reciting it during one of the final meetings. It delighted everyone who heard it. An excerpt: Oh, great was the captain and worthy the crew,

Very light verseTraugott Lawler

Of my many memories of Marie, whom I will miss always, this is perhaps my favorite. She read an article about a medievalist from an English department who left teaching and took a job as an executive at Maidenform Bra. It tickled her into writing an amusing Middle English poem about him, praising his job skills the way Chaucer does of the pilgrims in The Canterbury Tales, culminating in this brilliant line: “Wel coude he knowe a B-cup from an A!” It’s especially witty because Chaucer rhymes on the letter A in two places. For Marie’s retirement party, at which I knew she would perform on the piano, I decided that she too belonged among the pilgrims, and I wrote and recited a portrait of her in Middle English. It ended with yet another rhyme on A, a tribute to her Maidenform rhyme: In youthe hire litel fingres lerned to pleye

Yale Daily NewsWhen Yale’s Elizabethan Club celebrated the 450th anniversary of the birth of Queen Elizabeth I, Borroff, with her curly red hair and dignified bearing, was a natural for the starring role. View full imageRhymes for the radioLorraine Siggins

In 1966, Marie and I were among the first Fellows of the newly opened Ezra Stiles College, whose Master, Richard Sewell, was determined to have women Fellows. I was a very young psychiatrist and in awe of Marie, as she was so erudite and seemed austere. At that time I used to wake up to a morning show on a Hartford radio station hosted by Bob Steele. It was predominantly a sports station, and he told many corny jokes. One morning I was startled to hear him say, “I am now going to read you a limerick, written by my good friend Marie Borroff of New Haven.” I was so surprised that my first thought was “How could there be two Marie Borroffs in New Haven?” At the next Fellows’ meeting, I took my courage in both hands and asked Marie if she by chance knew of a radio host called Bob Steele. She burst out laughing and said, “Oh, yes! I am a big fan of his. I even have an autographed photograph.” I was amazed. The limerick was my introduction to Marie’s humor. I came to see that she had the ability to hold together her love of esoteric Old English texts and her love of Bob Steele’s radio program. She did not see them as incompatible. I am so grateful to Richard Sewell for giving me the opportunity to have a 50-year friendship with this extraordinary woman.

Manuscripts and ArchivesBorroff, front and center, the lone woman in this 1967 photo of the tenured faculty in English at Yale. View full imageShe lastedLangdon Hammer ’80, ’89PhD

In the Yale English department chair’s office, there is a group photo of the tenured faculty taken in 1967. Twenty-five illustrious professors are pictured. Two are Jews. All are white. One is a woman. Marie Borroff, in a skirt, with her knees and ankles neatly pinched, is seated in the center of these men in ties and jackets. William K. Wimsatt, master New Critic, looms directly above her at six feet and four inches (some say taller), his arms crossed, calmly dominating the group. But there is more than one way to be indomitable. Imagine you are the first female professor in that department. You can’t attend faculty meetings because they are held at Mory’s, an all-male club. Reflect on how much you would have to prove, and how much you would have to overlook, or be silent about. I came to Yale a decade later, and the picture had changed. There were women in the classroom as students and faculty, which I took for granted, failing to appreciate how recent an addition they were. Soon women joined Marie at the tenured English faculty meetings where careers were decided (these were no longer held at Mory’s). I never took a class with her. To my 20-year-old self, she seemed rather sober and austere in the manner of another generation. A friend of mine in graduate school, a stylish young woman, was assigned as a teaching fellow in Marie’s popular lecture course on Modern Poetry. In one staff meeting, Marie talked skeptically about Romantic poetry and its myths of genius. My friend cheekily put in: “I say, Die young and be beautiful.” Professor Borroff gently replied: “Wait and see. You may change your mind, my dear.” Marie lasted. At the age of 88, she published The Gawain Poet: Complete Works, a perfect merging of creativity and scholarship. As a medievalist, she understood everything in long perspective. Her training also seemed connected to her practicality. She was steeped in philology, an empirical discipline. That orientation set her apart in the era of high theory and postmodern verse experiment. She believed in the fundamental importance of language and its history to every aspect of literature. Etymology, connotation, syntax, grammar, and the sounds of words—language is what poetry is made of, and it is the business of critics and teachers to understand and explain it, she seemed to say. After retirement, she returned to the classroom annually to lecture in my course on Modern Poetry, which I’d inherited from her. Her topic was always the same: Wallace Stevens’s late long poem “The Auroras of Autumn.” But every year the lecture was different. Delivered without notes, it was a model of what it is like to read a poem repeatedly, to live with it, letting it speak to and for you each time freshly. The constancy of change within the cycle of the seasons, and the knowledge that the world was here before us and will remain, however changed, when we’re gone: these were Stevens’s cosmic themes, and Marie’s.

Borroff loved many things, including dancing, performing in plays, playing the recorder, and costume parties. Here she’s dressed as an upscale raven with a cigarette holder; the note on her head reads, “Quoth the raven, ‘It’s a bore.’” View full imagePolitics and wisdomLeslie Brisman

It is a little over 50 years since I had the extraordinary good fortune of meeting Marie Borroff. In those days, there was no such thing as a “job talk,” at least not for candidates for instructorships in the department—and it was as instructor, not assistant professor, that one aspired to place a foot on what then was not even called a tenure “ladder.” One thought of a position at Yale as something more like a subway strap, to hold while one could till one had to get off. The interview took place over lunch in what was then the Faculty Club, and I had the uneasy feeling that I was being judged less by my intellectual interests and potential than by my manners. For this I was totally unprepared. I was seated between Professor Giamatti and Professor Borroff, the former of whom slapped me heartily on the back and growled, “Les, have a beer!” What was this? An invitation? An order? A trial? I heard others ordering martinis and wondered if there were a schism between the beer drinkers and the hard-liquor professors and I was being asked to declare my allegiance to one school of criticism or the other. I thought of William Morris’s angel who offers Guenevere the choice between a blue cloth and a red, and “No man could tell the better of the two.” When she says, “God help! Heaven’s colour, the blue,” the angel makes his definitive judgment: “Hell!” But Marie came to my rescue, whispering in my ear, “Don’t listen to him. You don’t have to have a beer!” I think I audibly whispered, “Heaven!” Though the Faculty Club did not long survive after that, and, more important, the system of interviewing new PhDs changed radically for the better, what did not change except to grow more and more lovely was Marie’s careful mentorship and friendship. She was already my model before I set foot in New Haven, because I knew her both as a medievalist and as a most illuminating reader of modern poetry, and it was my great ambition—more important to me then than succeeding at Yale—to study, teach, and make contributions to more than one subspecialty. In the years that followed, I consulted with her often on a variety of topics, from difficulties in Wallace Stevens to Chaucerian pronunciation. (She was, and ever will be, thanks to recordings of her reading, the great inheritor and promoter of Helge Kökeritz’s masterful guide.) But most extraordinary, and most important, were the times she whispered something like the line with which she’d introduced herself to me at the Faculty Club: “Don’t listen to him.” These were never partisan or arbitrary preclusions of points of view, but moments of gentle reassurance that I could stand my ground when it was a matter of principle, and not fear the wrath of a superior. One such occasion deserves special mention. I was put in the terribly awkward position of being asked to pass formal judgment on a dissertation that I thought unworthy, knowing that the dissertation director, a mighty force among the senior faculty, would be furious if I failed the piece. Marie (I discovered later) shared my judgment that the dissertation should not pass, but with characteristic decorum she did not share her opinion with me till I had written my report. What she did do before that, and it meant the world to me, was to assuage my fear that it was my conscience or my career that was at stake. And she did this quietly, sweetly, and I am quite sure with a recollection of that very first piece of advice in the Faculty Club. What she said was: “You don’t have to drink his beer.” I lift my virtual champagne glass to toast her elegance, her perceptiveness about both poetry and people, her personal warmth, her truth.

The comment period has expired.

|

|