loading

loading

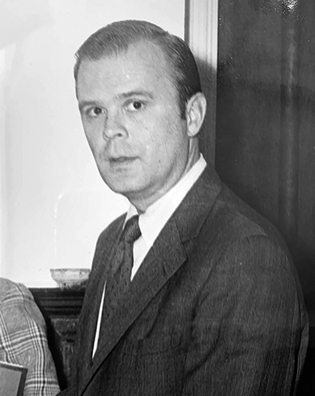

featuresThe women who changed Yale College: Sam Chauncey interviewFormer university secretary Sam Chauncey '57 recalls the bumps on the path to coeducation. This interview was edited for length and clarity.  Manuscripts and ArchivesHenry “Sam” Chauncey Jr. ’57 spearheaded the coeducation effort with Elga Wasserman ’76JD. “You pushed me into this. You’re going to make it work,” President Kingman Brewster Jr. ’41 told him. View full imageHenry “Sam” Chauncey Jr. ’57 spent 22 years working in the Yale administration: as an assistant dean of Yale College, as a special assistant to President Kingman Brewster Jr. ’41, and as secretary of the university, among other positions. Chauncey and the late Elga Wasserman ’76JD were the two people assigned to implement coeducation in Yale College in 1969. Chauncey is now retired and living in New Haven; editor Kathrin Day Lassila ’81 spoke with him about the preparations.

Yale Alumni Magazine: I’d like to ask you to just tell the whole story. You can start anywhere. Sam Chauncey: In 1956, Arthur Howe [’43], who was the dean of undergraduate admissions, was interviewed in the New York Times. It was primarily on the subject of minority admissions, but in the course of that interview, he also said he thought women should be admitted to Yale. And that caused quite an uproar. And Whit Griswold [’29], who was the president, called Arthur in and said, “Arthur, I want to say two things. One is that I think you’re right; we should have women at Yale. The other is, don’t ever say it again publicly.” Howe is a person in Yale history who’s been underestimated. He was really the first one to make a major effort towards minority recruiting. But he also was the first one to talk about coeducation.

But it wasn’t until the 1960s that the idea entered the Yale mainstream. What a lot of people forget, of course, is that the majority of universities in America were coeducational, particularly the great state universities. Of the Ivy League, Harvard had Radcliffe, Brown had Pembroke, Columbia had Barnard, and Cornell and Penn had women. People keep talking about coeducation as if this was some magical thing that never happened before anywhere else. But Yale was just hopelessly behind the times. One of the things I’ve always believed about universities is that the major changes that occur in them usually are caused by outside forces, not by internal forces. And I believe if there had been no feminist movement in the society at large, Yale never would have gotten coeducation.

What kept it from happening sooner at Yale? The pressures that were being brought to bear on Yale from the outside were not strong enough to convince Kingman Brewster [’41, Yale’s president] that Yale should be coeducational. Kingman and his wife Mary Louise were both born around 1920. They belonged to a generation that firmly believed that single-sex education was the right thing. So Kingman and Mary Louise were unalterably opposed to coeducation. And I would say Mary Louise even more than Kingman, although they were a couple who were fused at the hip. They were good friends with Alan Simpson, the president of Vassar, and his wife Mary. Mary Louise Brewster had gone to Vassar and was a trustee there. Every three months, the Brewsters and the Simpsons would spend a weekend at the Old Drovers Inn in upstate New York. And it was there that the plan was hatched to talk about moving Vassar to New Haven.

So at this point, the Brewsters were persuaded that there should be women at Yale, but kept separate? I wouldn’t say that. I would say the Brewsters were persuaded that something had to be done. And this was their solution. A committee was appointed, a study committee made up of half Vassar, half Yale people. I was the chair of the Yale committee. The plan was to move Vassar to the Divinity School campus. The Divinity School was going to move to Park Street behind Davenport and Pierson, and Vassar would get the Divinity School campus plus the Farnam Gardens area and all that up on the top of the hill. So the committee reported on a night in October of ’67. And I will never forget the dinner in the president’s house at Yale. The Vassar group was on one side of a great big table, and the Yale group was on the other side, and in the middle of the Yale group was Edwin Foster Blair [’24, ’28LLB], who ultimately was the only Yale trustee to vote against any kind of coeducation. He just couldn’t stand the idea. But the dinner went nicely, and everyone was having a good time. And while coffee was being served, a Vassar trustee named Mary St. John Villard reached down into her pocketbook and brought out a bejeweled pipe. She carefully filled it with tobacco, and she lit it. Well, Edwin Foster Blair turned a shade of red that very few human beings can turn. He was appalled that any woman would smoke a pipe in his presence.

Smoking at a dinner was okay at that time, right? Oh, sure. Women could smoke cigarettes; that would have not been considered improper. But to see a woman tapping tobacco into her pipe was something that I had never seen before. Well, I always thought that she was sending a signal. I don’t know for sure. But the Vassar trustees ultimately turned down the proposal. And the Vassar archives reveal that it probably was because of alumni pressure and faculty pressure.

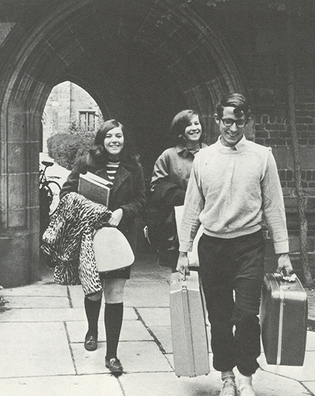

So Yale didn’t have a partner. Yeah. While all this was going on, though, the student body at Yale was probably split about 50–50—that is, only about 50 percent of the students wanted coeducation. But the ones who wanted it were very courageous and very vocal. Lanny Davis [’67, ’70LLB], who’s now a well-known lawyer in Washington, was the editor of the Yale Daily News, and he beat us to death with editorials about what a stupid administration we had and so on. Then there was a guy named Avi Soifer [’69, ’72MUrbS, ’72JD], who decided he was going to have Coeducation Week. And he marched into the dean’s office and he said, “I just want you to know I’m going to invite 200, 300 women from the women’s colleges to come and spend a week here, and they’re going to live in the dorms and so on. And if you don’t like it, you can kick me out, but we’re going to do it.” So the university had to sort of give in, and these women moved into the colleges, ate their meals, and went to the classes. It was a great event.

That’s an administrative miracle for a college student to manage. Absolutely. It was a big job. But the fact of the matter was that, on the morning after Yale learned that Vassar had turned us down, I said to Kingman, “Kingman, there’s a snowball coming down the hill, and you have a choice: you can be under it, or you can direct it.” He looked at me and he said, “Okay, you pushed me into this. You’re going to make it work.” And the Yale Corporation did approve, by a vote of 16 to 1, the admission of women to Yale College.

Do you think the man who couldn’t stand the pipe was still scarred by that? Oh, he was scarred for life. But anyway, Kingman asked Elga Wasserman [’76JD] and me to cochair the committee on coeducation, which was supposed to make it happen. Elga was a wonderful woman who was a chemist by training, a PhD in chemistry. She was in the chemistry department, but in accord with those days she did not have a tenure-track position. Her husband [the late Harry Wasserman] was a full professor of chemistry. She’d worked in chemistry for a while, and then she became assistant dean of the Graduate School. Kingman chose her because she had the happy combination of being a faculty member with a PhD who also had administrative experience.

So what was involved in making this happen? Well, we had a real time problem. We made the decision in December of ’68. In order to have an admissions program, we had to be ready in early February to get the work done—to meet the various deadlines we had to meet. We had to create 500 new living spaces, because we were not building any incremental buildings of any kind. Elga and I divided responsibility. Her job was to be concerned about academic things, to see that when the women got here there were people they could turn to, being a little more aggressive on recruiting women faculty, and that kind of thing. My job was to worry about administrative aspects like how we are going to get the admissions sequence done, how we are going to house the people. We had a terrible time with the physical plant, because there were buildings in which there was not a single ladies’ room. I would have to say that, because of the amount of time we had, we didn’t do a very good job of getting this place ready. I think the women came to a place that was hopelessly masculine, a problem I think still exists. It’s not hopeless now; it’s just there.

After the decision was made, what kind of resistance did you encounter? Those opposing coeducation were a substantial portion of the undergraduate body, a substantial portion of the older faculty, and a group that we never expected: women who worked at Yale. The older ones, such as the administrative assistants in the master’s offices, were mother figures, and these were their boys. The boys came to them for motherly advice. The younger secretarial people and so on were dates, and they saw the admission of women as providing too much competition for them. We actually had a reference librarian who announced to Elga that she would not speak to a Yale woman undergraduate. Somebody had to move her into another job.

Tell me more about how the faculty reacted. A lot of the older faculty just couldn’t handle the change. I’ll give you an example: a very distinguished professor of history announced to his first class that had women, “I’ll lecture for 35 minutes, then we’ll have discussion, and then I’m saving five minutes for the women’s point of view.”

Manuscripts and ArchivesAn uncaptioned photo from the 1969 Yale Banner likely depicts Coeducation Week, a student-organized event in which nearly 700 women from other colleges came to Yale to stay in the residential colleges and attend classes. View full imageSo the women are just on the side, watching. But we can give them five minutes. That’s right.

What about the admissions process for those first women? Elga and I did the whole thing. That is, the admissions office did the mechanical paperwork of sending out stuff and getting in stuff, but Elga and I admitted the entire first-year class, 250 women.

So you were the admissions committee for the women? That’s correct. I don’t know how many applicants we had—maybe 4,000. Admitting the upper-class women, the 250 sophomores and juniors, was much easier, because we had college transcripts to go on. And many of them were transferring from existing coeducational institutions. The first-year students were harder, because we didn’t know what it would take to come to Yale in this fairly hostile environment. So we had some interesting criteria. One was that if the applicant had four brothers, we admitted her almost immediately. If an applicant was an athlete—particularly in the physically tough sports where people bump into each other—or a star violinist, or musical, or artistic, we figured, well, if they’re disciplined enough to have gotten to that degree in their endeavor, they probably can handle this situation. So we were looking for a human being that we thought could take some punishment. I have to say I think we did a pretty good job of it. I don’t believe any woman dropped out in the first year, and I don’t think many dropped out afterwards.

There was a dispute about housing the women. Kingman decided that he didn’t want any woman living in the same quarters as men. So all the first-years lived together in Vanderbilt Hall. He decided that we would take Trumbull College—because I think it was the smallest college—and we would make it an all-women’s college. We had a meeting with the students in Trumbull to announce this, and all hell broke loose. That was actually the only time, including May Day [1970, when activists from all over convened on campus], when I was concerned about whether Kingman would come out alive. The students had built a platform for him to sit on that was made out of cardboard and peanut butter, as far as I could tell. I was sure the whole thing was going to collapse, and that when it collapsed they would all kill him. But their anger was such that he did a smart thing and said, “Okay, I’m wrong.” So we distributed the 250 women in each residential college but in a separate entryway [in each college].

Manuscripts and ArchivesThe late Elga Wasserman ’76JD oversaw coeducation with Chauncey. He’d like to see a building named for her; there is, however, an Elga Wasserman Award, given each year to a senior “who has shown extraordinary commitment to the advancement of social justice and gender equality at Yale College.” View full imageWhat happened to Elga Wasserman after the transition? Unhappily, she’s more forgotten than she should be. She achieved an enormous amount in the relatively short number of years that she did the job. Elga and I got along beautifully. We understood it. But she and Kingman did not get along. Throughout her time in charge of coeducation, there was a never-ending tension between the two of them. Elga saw her role as a kind of missionary leader. She always pushed for more than she knew she was going to get, which was smart diplomacy. Kingman was not used to dealing with a woman who was as intellectually aggressive as Elga was. I’d spend hours mediating this battle. She got very frustrated and decided to leave. She went to the Law School and became a fairly successful lawyer.

When did she leave? About three years after coeducation. In a way, it’s a kind of tragic story that she’s never been honored in some way by Yale. The university should honor her with a building or a distinguished lectureship or something.

During the debate over coeducation, President Brewster promised to continue educating “one thousand male leaders” every year, which necessarily would keep the numbers of women down. How did he get out of that pledge? Well, one of the loudest alumni complaints about the admission of women was that Yale had graduated one thousand men every year, and that we’d had so many presidents and so many secretaries of state and so many of this and that. And if you were cutting that number, we were affecting the leadership of the country.

And just graduating a bunch of housewives. That’s right. Exactly. And so, Kingman latched on to the promise to continue to graduate “one thousand male leaders” every year, primarily to shut the alumni up. But he got himself caught in a bind. The alumni opposition disappeared, but he had made the promise, and there were always a few alumni who said, “You promised this, and you’ve got to stick with it.” And it took him and me and other people a while to realize that we had created a monster in that phrase. Because we had no way to expand the college to admit more women—remember, in 1970, we attempted to build two new residential colleges to house all these incremental students, and we got turned down by the city. And so we were in a terrible physical-plant bind. Finally, we began to let nature take its course and even up the numbers.

We’ve talked about some things that went wrong. Was there anything that really went right that surprised you? I guess maybe what pops into my head is admissions. That is, that first group of 500 women were really spectacular. I think we were worried that we were going to have problems—of an individual not being able to handle it, or being attacked, or any number of scenarios. Of course, they did have some problems, and of course they had complaints. But the truth of the matter is they were a really good bunch of pioneers. They were really exciting and fun. At the end of the first year, Elga and I both felt that, given how little time we had to prepare, we were damn lucky that we’d gotten through it and it had gone as well as it had.

I thank you. I got to go to Yale. It was the right thing [for Yale] to do. The three things that have meant the most to me have been the admission of women, the admission of minorities, and getting through May Day weekend alive.

The comment period has expired.

|

|