The admission of women has changed Yale College in countless ways. The following stories are excerpted from Yale Needs Women: How the First Group of Girls Rewrote the Rules of an Ivy League Giant (Sourcebooks, September 2019), by Anne Gardiner Perkins ’81. They are about two of the many women who had an impact: Shirley Daniels ’72, who joined the effort by black students at Yale to increase their numbers and ensure their voices were heard; and Lawrie Mifflin ’73, who, along with varsity tennis captain Diane Straus ’73 and many others, helped establish women’s varsity athletics at Yale College.

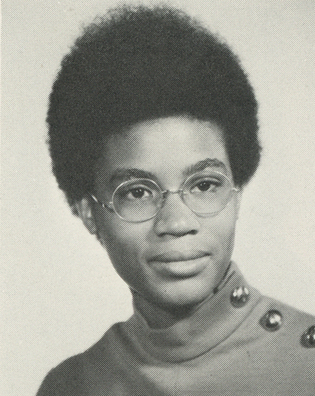

Shirley Daniels ’72 transferred to Yale to take advantage of the new Afro-American Studies major. She also volunteered in the Black Student Alliance at Yale, where she oversaw a major effort to recruit black students to Yale and help them succeed there.

View full image

Shirley Daniels

In Shirley Daniels’s first fall at Simmons College, she’d met a guy named Sam Cooper, a black sophomore from Yale who told her about the Afro-American Studies major that Yale would begin offering the next year. It would be one of the few in the country. Sam said Yale was accepting transfer students as well as freshmen. “Why don’t you apply?” he asked her, and so Shirley did, writing with her whole heart why she wanted to major in Afro-American Studies.

At Yale, Shirley lived in Timothy Dwight, where she was one of five black women students. From her first days at Yale, though, Shirley spent a lot of her time at “the House,” the nickname the black students gave to the black student center that Yale had just opened on Chapel Street. “It was a place where blacks could go where they didn’t have to worry about what they said, what they did, what they believed, because of being in mixed company,” said Shirley. Shirley never experienced any overt racism from students at Yale. But that did not mean it was comfortable to be one of the few black women in what was still a school of white men. Classroom interactions could be difficult. “They would sometimes look at me like I’m ‘the black opinion’; I’m ‘the female opinion,’” said Vera Wells, [a] junior who was in Timothy Dwight with Shirley. “It’s not that they meant to be cruel. It’s like I was a curiosity factor.”

Shirley did not have white friends at Yale, but that was through her own choice. She was oriented instead toward the black students at Yale and the black community of New Haven that surrounded it. Nearly every black student joined the Black Student Alliance at Yale (BSAY), which was in its third year in 1969. Through [Glenn DeChabert ’70] and BSAY member Ralph Dawson [’71], Shirley learned how Yale’s black students had accomplished so much in recent years: the opening of the House, the Afro-American studies major, and the rise in black student enrollment.

Unlike in many of the white-led student organizations, women in the BSAY quickly rose to positions of power. At the end of the first semester, Shirley and her classmate Sheila Jackson were elected to two of the BSAY’s top leadership positions: Sheila became the BSAY treasurer, and Shirley became chair of the BSAY’s largest committee, the Recruitment, Tutorial, and Counseling Committee, which ran the group’s massive effort to recruit black students to Yale and ensure they graduated once they got there. During Christmas and spring breaks, Yale’s black undergraduates traveled to black high schools in a dozen different cities, from Los Angeles to Detroit, Little Rock, and Philadelphia. Yale paid the costs of the airfare, food, and local transportation; students stayed with family or friends. In addition to coordinating all those student visits, Shirley managed an annual budget of $10,000 and met regularly with Associate Director of Admissions W. C. Robinson, one of Yale’s few black administrators, and with Sam Chauncey, whom Brewster had charged with increasing Yale’s enrollment of black students. Shirley also managed the BSAY’s financial aid initiatives and its counseling and tutoring program for incoming students.

Shirley spent much of her last year at Yale immersed in research and writing. She was a research assistant for the new director of Afro-American studies, history professor John Blassingame. By spring, Shirley had landed a job that would let her continue the work she had led at the BSAY: helping black students succeed in college. She had been hired as assistant director of Yale Upward Bound, which provided tutoring and an intensive summer program for junior-high and high school students from three poverty-stricken schools in New Haven.

But first came graduation. In June 1972, Shirley received her bachelor’s degree with the major she had come to Yale for: Afro-American Studies.

---

Shirley Daniels earned her JD from the University of Virginia in 1977. After a career as a New York City lawyer, she enrolled in New York Theological Seminary and received a master’s of divinity. She is now a Baptist minister. Since graduating from Yale, Shirley has gotten to know and become friends with many of the women in the Class of 1972, both black and white.

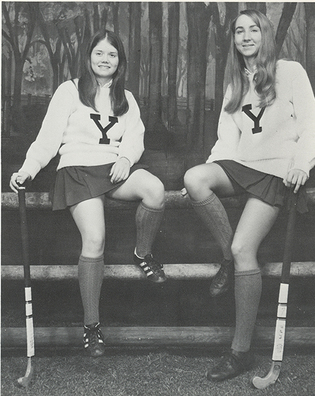

Lawrie Mifflin ’73 (left) and Sandy Morse ’74 took on an indifferent athletics department in order to build a varsity field hockey team. They were cocaptains of the new team in 1972.

View full image

The varsity field hockey team at play in its inaugural 1972 season.

View full image

Lawrie Mifflin

Fall 1969

After saying goodbye to her parents, Lawrie Mifflin set off for the other side of campus, where the athletic office was. “Where do I sign up for field hockey?” she asked the man behind the desk. He looked confused. There were no sign-ups, he told her. There was no team. There was also no women’s soccer team, no women’s basketball, and no women’s tennis or swim team or crew. Yale was not offering any competitive sports for women.

Damn it, she thought, I’m not going to let them stop me. Lawrie had met another student who played field hockey, and the two girls began talking. A few days later, handwritten fliers appeared on the entryway doors of Vanderbilt Hall: “Anybody want to play field hockey? Contact Jane Curtis in Vanderbilt Room 23 or Lawrie Mifflin, Vanderbilt 53.” A dozen girls [got] in touch. The women [would] hit the ball back and forth for an hour or so in one of the open spaces that lay between the Old Campus’s oak trees and its crisscrossing paths.

Fall 1970

Yale may not have known yet that it had a women’s field hockey team, but Lawrie and Jane certainly did, and so did the half-dozen colleges the two girls had written to over the summer to ask if they would scrimmage against Yale’s newest team. Since Yale showed no signs of providing a team for its women, Lawrie and Jane decided to do it themselves. The games would be nothing official, just a practice session really, but four nearby colleges and one local high school said yes, and after that Lawrie had what she needed to talk to the Yale athletic department. “Look, we can do this,” Lawrie said to the administrator who’d been assigned to deal with Yale girls. “There are schools who will play us. Would you just give us a field and some equipment?”

The strategy worked—sort of. Yale assigned the women’s field hockey team to Parking Lot A, which was used for football game tailgating. When the girls came out on Mondays after a home game, their field would be covered with charcoal briquettes and beer cans and other debris from football fans’ picnics, and they would have to begin practice by picking up garbage.

Fall 1971

Yale had granted club status that year to three women’s teams: field hockey, tennis, and squash. It was so easy to play sports at Yale if you were a guy. The men could just show up in September and choose from a menu of 17 varsity teams: baseball, basketball, crew (both lightweight and heavyweight), cross-country, fencing, football, golf, ice hockey, lacrosse, skiing, soccer, squash, swimming, tennis, track, and wrestling. To get even one women’s varsity team in some as-yet-unspecified future, women would need “to prove they were serious,” said Yale. So Lawrie and her teammate Jane Curtis set a goal for themselves. By next year, field hockey would have varsity status. Thirty women played field hockey that season. Lawrie and Jane set an ambitious schedule: Wesleyan, Trinity, Connecticut College, Southern Connecticut, and Radcliffe. The big game of the season would be against Princeton.

Fall 1972

In the fall of her senior year, Lawrie received a letter from Joni Barnett, director of women’s activities, letting her know she had succeeded. “Dear Lawrie,” it began. “My sincere congratulations to you.” The field hockey team had been made varsity. Every woman on the team got the same letter from Barnett, and each would receive Yale’s coveted varsity sweater, with the blue Yale Y on the front of it.

Yale allowed its varsity sports teams only one captain, but the women’s field hockey team had two: Lawrie and her teammate Sandy Morse. Both women, said Lawrie, “were leaders in their own way,” but Yale was not having it. “You just have to name one person as captain,” declared the athletic office. Lawrie and Sandy refused. “The team elected us together and you have to take us together,” they said, and Yale, somewhat surprisingly, backed down. In the hundreds of photos taken over the years of sports team captains at Yale, there is only one where the leadership is pictured as not one person but two. You can find it if you look hard enough. Lawrie and Sandy are wearing their white varsity sweaters, each with a big blue Yale “Y” on the front. They hold their field hockey sticks, lean up against the wooden fence, and stare out at the camera together.

---

In her last semester at Yale, Lawrie Mifflin covered women’s sports for the News. She earned a master’s in journalism at Columbia and worked at the New York Daily News and the New York Times. She is now managing editor of the Hechinger Report.

Mifflin adds: “A lament of women in the earliest coed classes was the difficulty in finding female friends. Teams certainly helped. Sandy Morse ’74 kept the team spirit thriving after I left. And it turns out a great legacy of the field hockey team is our amazing alumnae association. To start the team was one accomplishment; to make it a family with a living history is another, and that was accomplished by many team-spirited women who came after the first women.”

loading

loading