loading

loading

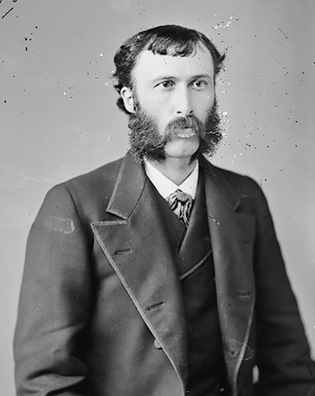

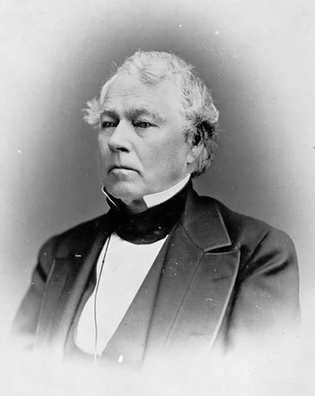

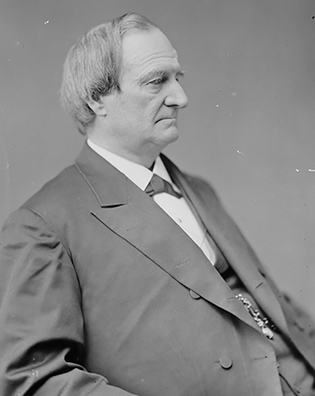

Old YaleWhen alumni got the voteIn the 1870s, the Young Yale movement pushed for reforms, including the election of trustees. Judith Ann Schiff is chief research archivist at the Yale University Library.  Manuscripts and ArchivesAfter 1901, trustees met in the Corporation Room in Woodbridge Hall. View full image Library of CongressThe first Yale trustees elected by alumni in 1872 included Young Yale activist William Walter Phelps ’60, (top), honorary degree holder Joseph Sheffield (center), and Alphonso Taft ’33. View full image Manuscripts and ArchivesView full image Library of CongressView full imageOn March 21, 1872, in an item on the front page of the New York Times, the Yale Corporation asked “all graduates of the College qualified to vote at the election of Fellows at the Commencement to send . . . the names of six persons whom they desire to nominate for the office of Fellows. The names of all candidates thus nominated by more than twenty-five electors will be subsequently announced.” This highly public call was letting alumni and the world know that, for the first time, alumni would be electing six of Yale’s trustees—or “Fellows of the Yale Corporation,” in official university parlance. The new era of Yale expansion and administration under Theodore Dwight Woolsey ’20, who had stepped down the year before after 25 years as president, would continue, with the assistance of the alumni. The move reshaped a Corporation that many people said needed to be modernized. In the 1790s, in exchange for vital financial aid from the state of Connecticut, President Stiles and the Corporation had added to its number eight seats for the governor and lieutenant governor and “six senior assistants in the Council of this State.” By the 1860s, Woolsey was building the college into a modern university. Under his leadership, Yale established the Graduate School, the Sheffield Scientific School (which was the state’s land-grant college until 1893), and the School of the Fine Arts. The Divinity School introduced a professional bachelor of divinity degree. At the same time, students and younger alumni formed a movement known as “Young Yale,” seeking modernization and more alumni representation. Most of the “successor trustees”—those chosen by the Corporation itself—were still ministers; those chosen by the state were current state senators and governors, who often served briefly and attended even less. In an unusually frank speech at an alumni dinner in 1870, wealthy alumnus William Walter Phelps ’60 declared that “the younger alumni are not satisfied with the management of the college,” and that the Corporation should not be governed by “Rev. Mr. Pickering of Squashville, who is exhausted with keeping a few sheep in the wilderness, or Hon. Mr. Domuch of Oldport, who seeks to annul the charter on the only railway that benefits his constituency.” In a May 25, 1871, article in The Nation, Daniel Coit Gilman ’52, a former Yale librarian who would become president of the University of California and subsequently of Johns Hopkins, laid out several ways the Corporation could be opened up to broader representation. Among them was the idea of the state giving up its seats. Just a few weeks later, on July 6, the Connecticut General Assembly passed “An Act relating to Yale College,” which provided for the election of six graduates as Fellows of Yale College “in the stead of the six senior senators of the state.” On July 11, the Yale Corporation accepted the plan. William Graham Sumner ’63, who later became a professor of sociology, declared in the Times on July 17 that “Young Yale wants action, and that action which will be most for the benefit of the College.” His advice: “Discuss the needs of the College and nothing else at the meetings of the Alumni. Urge that theory of education which regards scientific culture and discipline as the end to be aimed at, and advocate those measures which will put this theory in practice. Elect Alumni members of the corporation who had financial skill, and an intelligent appreciation of the destiny of the College. Raise money by popular and business-like methods, and unite all the graduates in the effort to do so.” A year later, at the July 1872 alumni meeting at Commencement, six prominent politicians, diplomats, and businessmen were elected to the Corporation. W. W. Phelps, who had spoken so forcefully for Young Yale two years before, was one of them. (He would later be a US Congressman and ambassador to Germany.) Another was Joseph E. Sheffield, railroad magnate and benefactor of the Sheffield Scientific School, who held an honorary Yale degree. The rest were lawyers and politicians: Alphonso Taft ’33, later attorney general and secretary of war; William Maxwell Evarts ’37, former attorney general and secretary of state; William Barrett Washburn ’44, governor of Massachusetts; and Henry Baldwin Harrison ’46, Connecticut state legislator and future governor. Seven years later, in an essay in James Kingsley’s 1879 history of Yale, Leonard Bacon ’20, successor trustee and longtime pastor of New Haven’s Center Church, wrote that the new nonclerical alumni were “not only decus but tutamen”—that is, not just an ornamental addition to the Corporation, but also a safeguard. They are, he said, “men familiar with [Yale’s] history and its ways, rejoicing in its past, assured of its future, and proud to repay, by any service in their power, some part of their personal debt to its founders and its benefactors.” Today, the Corporation has been restyled as the Board of Trustees, but each year, alumni still elect a trustee to a six-year term. Most often, they are selected from among candidates chosen by the Yale Alumni Association’s Alumni Fellow Nominating Committee. Candidates may also be nominated by petition. One vestige of Yale’s eighteenth-century governance remains. Although they play no part in the Corporation’s activities, the governor and lieutenant governor of Connecticut are still ex officio trustees.

The comment period has expired.

|

|