loading

loading

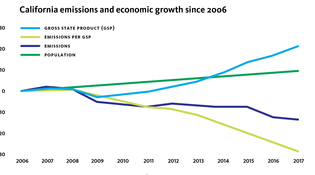

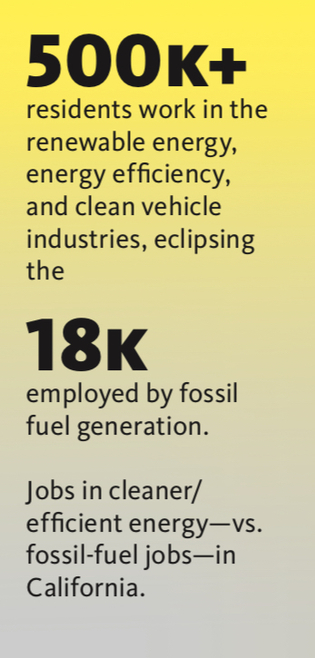

featuresThe climate in CaliforniaAmerica's most populous state has reduced its carbon output to 1990 levels. One determined Yalie has led the charge. Dylan Walsh ’11MEM is a freelance writer based in Chicago who covers science and criminal justice.  Michael KirkhamView full imageAn audience sits in foldout chairs on the gravelly western shore of Treasure Island, California. On a dais in front of them political dignitaries make themselves visible and, far beyond, the skyline of San Francisco rises from the pale, choppy waters of the bay. It is a Wednesday in September 2006. After a short round of media pomp, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger sits at a table in the center of the dais and signs the California Global Warming Solutions Act. To his left, projected on a screen via satellite link, the face of British Prime Minister Tony Blair looms gigantic. The legislation gave California a mere 14 years to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to what they had been in 1990. This was an ambitious path, demanding a 30 percent cut from business-as-usual projections. It was a solitary path, as well. Emissions nationwide had been rising for as long as records tracked them, as though this trend were written inviolably into the rules of growth and progress. The sitting president expressed no concern about the role of humans on a warming planet and positioned himself as openly hostile to environmental regulation. Other states had been tinkering with policies designed to slow emissions—renewable energy requirements here, efficiency regulations there—but nothing approached the grand magnitude of California’s effort. Industry decried passage of the law. “The oil companies hired very prominent economists to say this would basically shut down the state’s economy,” says Adrienne Alvord, who served as a lead congressional adviser on the bill before her current role as western states director for the Union of Concerned Scientists. “Of course, it didn’t pan out the way the fossil fuel industry anticipated.” California achieved its goal four years ahead of schedule, meeting 1990 emissions levels in 2016. The state’s economy, meanwhile, grew by 26 percent. In retrospect, the California Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 offered a declaration of hope in otherwise dark times, a modern city upon the hill. According to Alvord, “This is one of the most underreported success stories in the United States.”  Max GerberMary Nichols ’71JD, head of the California Air Resources Board, filed one of the first lawsuits under the Clean Air Act when she was fresh out of Yale Law School. View full imageAt one o’clock in the afternoon on a hot spring day in Sacramento, Mary Nichols ’71JD, current chair of the California Air Resources Board, walked from a lunch meeting to her office where she was scheduled to preside over four more meetings held back to back to back to back. “That’s a large part of what I do,” she explained later, as the blue of the sky darkened and the workday ended. She runs meetings. Fair enough. Meetings do take up much of her time. But for Nichols to wrap her responsibilities in such dull cloth is a modesty so extreme that it borders on untruth. Ask somebody else what Mary Nichols does and you get a different answer, with no mention of meetings. According to Ralph Cavanagh ’74, ’77JD, Energy Codirector at the Natural Resources Defense Council: “You’re dealing with the most influential environmental regulator in history.” Schwarzenegger appointed Nichols to be the chair of the Air Resources Board (CARB) in 2007, shortly after signing into law the California Global Warming Solutions Act, or AB32. CARB was tasked with spinning the spare 13 pages of legislative text into an effective and politically agreeable network of policies that would reduce the state’s greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. The undertaking was the first of its kind at such scale. It would touch every corner of the state’s economy—an economy, it’s worth noting, that fluctuates between fifth and sixth largest in the world. It would rouse the great oppositional beast of lobbying from within the state and beyond its borders. It would need to navigate legal headwinds from conservatives demanding less regulation and progressives demanding more. The project had no template to adopt or precedent to borrow. It was, in short, a modern bureaucratic expedition between Scylla and Charybdis. And yet CARB would ultimately fulfill its charge in 2016, a decade after it began and four years ahead of schedule. Thousands of employees at CARB and other state and county agencies all contributed to meeting this goal, but Nichols is distinguished as a supernatural catalyst, the person thrown into the mix who made the success of AB32 not just possible, but rapid, almost inevitable. When friends and colleagues reflect on the how of her success, they often get intensely adjectival, reeling off lists of defining characteristics—brilliant, tough, considerate, thoughtful, funny, a straight-shooter. But then, as often, their expansive descriptions trail off and the suggestion arises that these words only adumbrate something deeper, more essential, that accounts for Nichols’s accomplishments. “It’s really worth emphasizing that there is no one like Mary,” says Ann Carlson, a professor of environmental law at UCLA. “Her breadth of experience across every kind of environmental organization, from NGOs to the federal government to state government to foundations to universities, combined with extraordinary smarts, make her singularly capable of doing what she’s doing, and I’m not alone in thinking that.” Or as another colleague who described Nichols as “a legend” put it when asked to clarify how, exactly, she came to be a legend: “Because she’s just Mary. It’s who she is.”  Source: California Air Resources Board, California Department of Finance.View full imageThe air resources board is headquartered in Sacramento, but Nichols lives in Los Angeles. There, softened by humidity, the sun rises pale as a molten coin. Bobbing pumpjacks, like grounded flocks of birds, pull oil from small plots of land among the city’s sprawling flats and hills, adjacent to neighborhoods and nature preserves. Nichols and her late husband, John Daum ’69JD, arrived in 1971. They were coming off an international tour celebrating Nichols’s graduation from law school, a four-month exploration of Iran, Afghanistan, Turkey, and Central Asia after which they road-tripped from east to west across the southern United States and into the Los Angeles basin, where sunsets flamed unnaturally orange behind the curtain of nitrogen oxides. Nichols spent the first several months in L.A. studying for the California Bar and interviewing for jobs. After securing her own salary through a grant, she persuaded the Center for Law in the Public Interest to hire her, first as a clerk, and then, once she passed the Bar, as a staff attorney. The four founders had already laid claim to legal specialties that interested them, fields like nuclear power and land use, so Nichols was made the “air lawyer.” “I had no idea about how to do it, or even a great desire,” she says. “But they knew they needed someone to work on smog.” The story of L.A.’s afflicted air was by then an old one. Residents in 1903 mistook the dimness of smoke-screened daylight for an eclipse. Expanding industry in the early twentieth century cloaked the city in factory emissions. In the summer of 1943, an acrid plume of smog spread through downtown, restricting visibility to three city blocks and raising fears of a Japanese gas attack. In response, California created the country’s first regional authority for regulating air pollutants. In 1967, Governor Ronald Reagan set another precedent, approving legislation that created the Air Resources Board and consolidated regulatory power at the state level. But besides this administrative scaffolding, the field of environmental law remained amorphous. It was entirely unclear whether or not “environmental lawyer” was a legitimate and stable career choice. Yale introduced one course on the topic in Nichols’s final year there, a novelty of sorts couched in the logic and case history of property law that she never took. When she started at the Center for Law in the Public Interest, the Environmental Protection Agency and those sweeping first statutes bundled under its purview—the National Environmental Policy Act, the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act—were either in their infancy or not yet born. This general unformedness could have been a source of consternation for Nichols. What was she getting into? And to a limited extent, it was, but mostly it galvanized her. She wasted no time. In September of 1972, on behalf of the City of Riverside, she filed one of the country’s first lawsuits under the Clean Air Act. Residents of Riverside had relocated there, 50 miles east of Los Angeles, over the desert chaparral, to distance themselves from L.A.’s smokestacks and car-choked freeways. Many had been driven by the demands of health. And yet in August of 1972, smog from L.A., carried on an otherwise pleasant ocean breeze, climbed to such severe levels in Riverside that federal officials considered an emergency court order banning the sale of gasoline in the region. The Clean Air Act was two years old at this point, and California, under federal mandate, had recently submitted a proposal to meet the Act’s pollution control standards. The proposal had been egregiously inadequate and, given this, responsibility had shifted to the EPA to develop a revised plan for bringing California into compliance with the law. The EPA, in turn, had failed to provide this substitute. Now Riverside residents were suffering. Nichols sued, naming William D. Ruckelshaus, the EPA’s first administrator, as the defendant. Nichols won the case. No great reckoning or onerous judgment was handed down—just a court-imposed deadline for the EPA—but “this ended up being a monumental lawsuit,” says Linda Waade, who for decades has known Nichols as a friend and colleague. It established Nichols’s reputation in both the legal and environmental worlds. In 1974, Governor Jerry Brown appointed her to the Air Resources Board. The agency was relatively new then and not celebrated for its political clout. Nichols and two other appointees joined “with the mission to shake up the board,” she says. She was 29 years old, an east-coast transplant and Yale Law grad who had clerked one summer in the famously radical Oakland firm of Treuhaft, Walker, and Bernstein, mostly handling cases on the Vietnam draft, and now here she was among the entrenched and very male forces of Sacramento, fresh to politics, a rising environmental lawyer aggressively tackling the challenge of automobile pollution. “I must have been a somewhat interesting character from the point of view of the industries we were regulating.” Nearly a half century has passed, during which Nichols ran a gubernatorial campaign, led nonprofits, taught law school, worked in private practice, and served in the highest ranks of the Environmental Protection Agency. She is now back in Sacramento, back at CARB, regulating many of the same industries she was regulating in the seventies and eighties. The specifics of the work have evolved: she focuses as much on reining in greenhouse gases as she does on smog-forming pollutants. But the broader strategic context is similar. Dealing with greenhouse gases, she said in a 2018 talk at the University of Chicago, can be thought of as analogous to dealing with urban air pollution, just blown up to a global scale. It’s “an extension” of the same failure to think through unintended consequences of how we do business, of how we move ourselves and our things from point A to B, of, most fundamentally, how we generate and consume vast and growing quantities of energy.  Michael KirkhamView full imageModern climate change originates with the Industrial Revolution. The human contribution of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere was negligible until the combustion of coal, oil, and natural gas became the bedrock of economic growth. When scientists or policymakers talk about dangerously high concentrations of carbon dioxide, the unspoken comparison is preindustrial times. But there is a way in which this long historical view distorts the violent urgency of climate change. More than half of all the carbon that has entered the atmosphere since 1751 was emitted in the past 30 years. The problem has historical roots, yes, but the crux is contemporary. Even the best-case scenario these days is alarming. If we limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius over preindustrial levels—we’re currently one degree over—we can expect to lose 70 to 90 percent of coral reefs; nearly 300 million additional people will suffer water scarcity; droughts, on average, will be two months longer; 60 million more people will experience coastal flooding; cases of malaria will increase; food production, snowpack, and river levels will decrease; wildfires will grow in size and intensity; meteorologists may need to establish a “Category 6” for hurricanes; and $10 trillion will be shaved off global GDP. That’s a handful among many dismaying projections put forth by the scientific community. And yet hitting the 1.5-degree mark will require a feat of such concerted, international political bravura that it would be cause for laughter were the stakes not so high. Carbon emissions basically need to plateau by 2020—that is, next year—and cease entirely, worldwide, by 2050. As the United Nations’ scientific panel on climate change put it in a 2018 report, achieving this target requires transforming the global economy at a speed and scale without “documented historic precedent.” This is a challenge made more daunting by the fact that the United States, the largest economy in the world and the second-largest emitter of greenhouse gases behind China, is led by a president who disavows the need for action on climate change and who has very publicly and very repeatedly announced plans to bow out of the 2016 Paris Agreement, which encourages signatories to prepare a blueprint for keeping temperature increases below 2 degrees. Nor does Congress offer hope for a national solution. A recent analysis by the Center for American Progress Action Fund found that 150 members of Congress do not believe in the scientific consensus that human activity is making Earth’s climate change. This abdication of responsibility at the federal level has, incidentally, thrust California into a position of international prominence. Nichols has embraced the role, offering up CARB’s wealth of experience in air quality and greenhouse gas regulation to anybody who shows interest. “Hardly a week goes by in Sacramento where someone isn’t visiting from a foreign country and attending a workshop at CARB,” says Fran Pavley, a long-serving (and recently retired) California state legislator who authored AB32. In 2018, CARB hosted more than 35 countries in discussions on a range of subjects, from air pollution controls and regulatory enforcement to zero-emission vehicles. They established a memorandum of understanding with Mexico regarding transboundary air quality issues, and have other MOUs with Japan and India. They have also supported China as it prepares to launch the world’s largest carbon market in 2020. “The politics of these issues are hard, and they are not uniquely easier in California because we’re ‘so green and so virtuous,’” Nichols said in a 2018 public meeting. People are universally resistant to paying more for the things they rely on, like gas and electricity. But CARB was nonetheless pushed by legislation to tackle the issue of carbon pricing, “and now we have a model to hold up to the world.” In some ways, this model is more important than the specific results it has obtained. That California reduced its greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels is laudable, but, from a numbers perspective, irrelevant. The state produces less than one percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. The United States as a whole accounts for 15 percent. That’s a disproportionately large number given the US comprises only 5 percent of the world’s population, but even a radical plan to decarbonize the country’s economy would simply postpone by some number of decades or centuries the rise of a planet uninhabitable by humans. Every major industrial economy in the world, established and emerging, must get on board with the notion that human flourishing is not, and cannot be, dependent on the combustion of fossil fuels, and that a grand post-carbon future awaits. California is trying, for all of our sakes, to prove this proposition true.  Michael KirkhamView full imageEarly one day in April of this year, Nichols visited Riverside to tour CARB’s future 380,000-square-foot, $419 million vehicle emissions testing and research facility. It is currently under construction and touted by press releases as “one of the largest” and “most advanced” facilities of its kind. Initiating a project like this requires support from all kinds of people in all different places, but Nichols is especially grateful for the financial contribution, if unwitting, from one party: “Thank you, Volkswagen,” she says. CARB was central to the revelation that Volkswagen spent years selling cars designed to game diesel emission tests. As a result, the agency captured a portion of the multibillion-dollar settlement, including $154 million for the Riverside facility. Another $800 million is going toward the development of statewide electric vehicle charging infrastructure. Automobiles have long been the cornerstone of Nichols’s regulatory agenda, and perhaps the crowning achievement of this work was persuading the Obama administration to adopt, at the federal level, California’s greenhouse gas emissions standards for passenger cars. The rule went into effect in 2009 and demanded a steady rise in fuel economy nationwide ending at the equivalent of 35.5 miles per gallon by 2016. A second phase of the rule bumped the goal to 54.5 miles per gallon by 2025. Nichols has described the ceremony where President Obama publicly announced the agreement as one of the proudest moments of her life. It was a “magnificent example of how government could tackle a very large and complicated technical and legal problem and tie together two agencies with very disparate missions that don’t, historically, work together,” she says. The rule is now under attack by the Trump administration, which has argued not only for halting the advance in fuel efficiency, but also revoking California’s ability to set its own more stringent automobile emissions standards, a longstanding allowance written into the 1970 Clean Air Act. Nichols, unsurprisingly, is fighting back.  View full imageAlso unsurprising among those who know her: the winds of dispute blow favorably her direction. “She always wins,” says Wendy James, who has worked on electric vehicles and clean air in California for decades. “I’m not aware of any instance where she has lost.” In the present case, Ford, Honda, Volkswagen, and BMW of North America, which together constitute 30 percent of US auto sales, negotiated a voluntary agreement with CARB that achieves roughly the original goal with one extra year tacked on the timeline. Absent serious attempts at compromise by the federal government, California and industry found common ground and offered silent rebuke to DC. That the auto industry stood by Nichols’s side is not a product of chance. She has long understood that adversarial relationships, though sometimes unavoidable, are useless; she seeks and finds consensus. Robert Wyman, an attorney who represents industries facing environmental regulation, and who calls Nichols “a national treasure,” attributes this to her willingness to listen without prejudice. “She is not as an extremist or ideologue,” he says. “She is obviously committed to an environmental agenda, as well as she should be, but from the very beginning one of the reasons she’s been so effective is that she has always been open to different ways to achieve her goals.” Wyman witnessed this inclusivity in the early nineties, shortly after the Clean Air Act had been revised with stricter standards for certain air pollutants. Nichols was a senior attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council at the time. (She founded the L.A. office in 1989.) Wyman was representing a coalition of 25 companies all trying to sort out how they would meet the tighter regulations. When he approached Nichols to ask if she would like to work with him, she readily agreed. He again witnessed it on a national stage when, in 1993, Nichols was appointed by President Clinton to head the Air and Radiation Division of the EPA. While there, without any particular authorization or approval, she asked executives from the country’s major energy producers if they would join her for discussions on the design of a market-based approach to greenhouse gas regulations. She and her staff were aware that climate change loomed as the next big regulatory issue, and she argued that industry would be better off cooperating early with regulators to find the least costly solutions to curbing emissions. The energy sector ultimately rejected the offer. Wyman suspects they regret this decision. “With Mary, the reason I love her so much, is because she’s about making a difference in the world, and you don’t do that by yourself,” says Felicia Marcus, a friend who worked with her at the EPA and who most recently chaired California’s Water Resources Control Board. “You bring along government, business, the whole family that you need. Some people lick their wounds about how right they are and how wrong everyone else is. Mary’s into being effective.”  View full image View full imageThe air resources board now faces the challenge of reducing greenhouse gas emissions to 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030, a vastly more ambitious goal than that originally set by AB32. Beyond automobiles, they are looking at forestry and agriculture practices, urban planning, carbon capture and sequestration technologies, concerns as far afield as how California invests its pension fund. This work is made more urgent by the expectation that California will be carbon neutral by 2045. Nichols has been in the environmental field for her entire life, and it would be easy to assume such longevity is possible only through some bottomless source of optimism. In fact, these days especially, pessimism clouds her outlook. Where the current federal administration shows greatest competence and diligence appears to be in its efforts to dismantle decades worth of progress on environmental protection. It is fortunate, then, that optimism has no bearing on Nichols’s success. What does matter is that she is eminently pragmatic, and that this pragmatism is tied to a visionary outlook, and that both of these—her pragmatism and her vision—are animated by a “righteous indignation.” Her desire for justness is what has committed her for so long to the environment. This desire drives her concerns about smog and her concerns about climate change and her concerns about how these both fall hardest on those with fewest resources. This desire, looking back, is what drove her to serve as the chief attorney for the civil branch of Los Angeles from 1978 to 1979 where, among other things, she made investigations into police misconduct more transparent. This desire drove her to defend student mailings on birth control in 1972, to spend a college summer registering impoverished black voters in southwestern Tennessee, to take a bus from Ithaca, New York, to the March on Washington in 1963 while still a teenager. “Thinking about Mary as an environmentalist and only an environmentalist doesn’t do her justice,” says Cecilia Estolano, who has known Nichols since 1991 and worked with her at the EPA. “She has always been about trying to ensure that our democracy reflects the present and future folks who live here.” And this is why she pushes herself, along with her employees and the agency she leads, to create a world that seems impossibly at odds with the one we presently occupy. In one meeting this April, discussing the minutiae of environmental impact reports, she wondered aloud why the status quo was a given, then urged everyone present not to let “political feasibility constrain our imagination.” This was notable coming from someone who has spent a lifetime in politics, who is expert in the art of compromise, who is famous for her equanimity, who is, it seems, permanently lacquered with politesse, courtesy, good humor, and a general overwhelming niceness. Below it all is her comprehensive understanding of where we are and her superheated commitment to where we must go. Note: in the print magazine, Ralph Cavanagh's title was incorrect. It has been corrected here, to Energy Codirector.

|

|

6 comments

-

Bobbin Gralsh, 11:30pm January 09 2020 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Kathrin Day Lassila, 3:17pm January 12 2020 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Mary Quinlan, 8:50pm January 13 2020 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Thomas Becker, 11:37am January 14 2020 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Margaret McCall, 11:57am January 14 2020 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Willim (Billy) Funderburk ('83 MC), 2:53am January 19 2020 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.Molten coin?

Yup. Check out Merriam-Webster:

Definition of molten:

1 : fused or liquefied by heat : melted

// molten lava

2 : having warmth or brilliance : glowing

// the molten sunlight of warm skies —–T. B. Costain

What impressive models -- both this woman, and the comprehensive environmental model she has guided. Thanks for celebrating this alum.

In a recent article in the LA Times, Nichols blatantly stated that the reason California is suing EPA is to delay EPA's actions in the hopes Trump is voted out of office before EPA's regulations take effect. It's stupid on her part to admit that California is using the courts in such a disrespectful manner.

Incredibly inspiring for a new Californian in graduate school in the energy space! Hoping that one day I can be anywhere near this effective.

Without Mary Nichols, the environmental and climate movement would be dead and any hope of bridging the yawning divide between activists and mainstream and EJ and market based policy schools of thought would be lost. Mary carried the clean air and decarbonization torch through four gubernatorial administrations (Brown I, Schwarzenegger, Brown II and Newsom), one presdential administration (Clinton) and two mayoral administrations (as chair of the largest US public utility, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power for LA Mayors Villaraigosa and Bradley). She's mentored legions and even more call her their role model (I being one).

As someone who spent time in New Haven doing more than chairing the Tang team, rowing heavyweight crew, laying out Yale Banner pages, selling Beer Gloves or lighting Morse Dramat productions, I thought about clean air all the time; I was an asthmatic who spent close to 100 days in oxygen tent and almost lost my life to dirty air and allergy induced asthma 3x before high school. Meeting Mary through activist and investor Tom Soto began my journey to understanding the interrelation of greenhouse gases and air toxics.

Mary has somehow managed to balance for Governors Schwarzenegger, Brown and Newsom interests of utilities, communities, taxpayer activists, EJ activists, coastal elite environmentalists, auto companies, Wall Street, insurers and even, on occasion, oil and gas interests, without getting co-opted. Her story is legend. It needs to be retold over and over. I look forward to her memoir or a book on Mary. Thank you for the tribute to her and to the State of California.