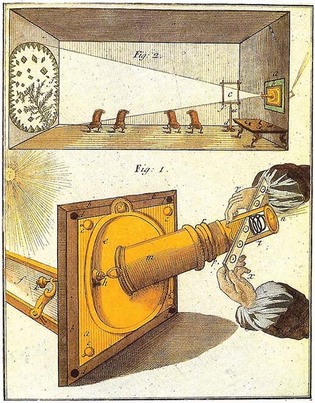

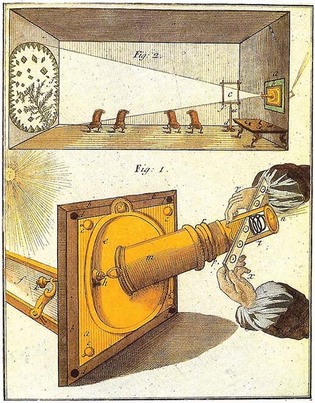

The illustration is from Martin Frobenius Ledermüller’s microscope book, published in various languages in the 1760s.

View full image

Thomas l. Lentz ’64MD

With the aid of some flat strips of bone, ivory, or wood—plus a little mica and a sunny day—the solar microscope would have helped eighteenth-century scientists observe the details of nature.

View full image

Six months ago, with virtually no warning, college faculty and students around the world were dropped into the deep end of the remote teaching pool. While I think all of us yearn for the day we can get back in the classroom, we have improved virtual learning by mastering the finer points of Zoom, developing live interactives, and thinking creatively alongside our students. This experience has underscored for me how much in general we depend on technology to share what we know and to learn from others.

It would be easy to think of teaching technology as a modern concern. However, people have been working for centuries to find better ways to connect with their audiences. One example is the solar microscope, first developed around 1740 by British instrument maker John Cuff. Microscopes were invented in the early 1600s, to allow observers to examine objects and organisms too small to see with the naked eye. Throughout the centuries, they transformed our understanding of the biological world.

The solar microscope is an early optical projector, a sort of great-grandparent to the LCD projectors we use today. It would project an enlarged image of a specimen onto a wall or screen, allowing an audience to experience it together. Evidence that solar microscopes were of interest at early Yale is provided by the instruction from President Ezra Stiles in 1789 to order a model with the “the latest improvements” from London. That first solar microscope was purchased from Henry Shuttleworth at Ludgate Hill.

For at least a century and a half, the college mainly ordered its scientific instruments—what it called its “philosophical apparatus”—from the British capital, which hosted the largest instrument trade in the world. Sometimes Yale faculty traveled to London to oversee the purchases, as Benjamin Silliman did in 1806, when he bought a second solar microscope.

The Peabody Museum’s Division of the History of Science and Technology stewards a collection that includes many of Yale’s earliest scientific instruments. As the museum undergoes a major renovation, we are planning to include a dedicated gallery for this nationally important collection. Curator and associate professor Paola Bertucci and collections manager Alexi Baker have developed plans that include exploring how science was practiced and taught at Yale.

Thomas L. Lentz ’64MD has been generously aiding this cause. Lentz, Professor Emeritus of Cell Biology at the Yale School of Medicine, has been researching Yale’s early philosophical apparatus and donating the types of instruments that the college used to have but were apparently lost. The beautiful solar microscope (circa 1772) shown here is one of his donations; it stands in for Yale’s earliest solar microscope.

The microscope would have been attached to a shutter, with its rectangular mirror positioned out the window so that it could reflect sunlight into the instrument. A “slider” would then be inserted into it. Sliders—predecessors of the modern microscope slide—consisted of rectangular slabs of bone, ivory, or wood, pierced with a series of small holes called “wells.” Each well had a thin sheet of mica underneath. Each specimen would be placed into a well, which was then covered with another sheet of mica. Sunlight would pass through the mica and then through a screw-barrel microscope, to project a magnified image of a specimen.

This superb solar microscope has been disassembled into its mahogany case. The open drawer holds sliders, some of them still containing minerals, plants, and insects. On the inside of the lid is the original contents list, handwritten in English in 1772.

loading

loading