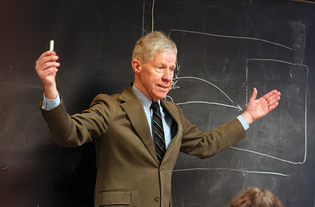

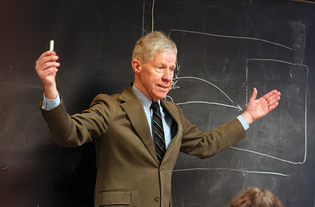

Mchael Marsland

Charles Hill, who died in March, cofounded Yale’s program in Grand Strategy.

View full image

Few Yale faculty members have taught a wider range of courses than Charles Hill, who died in New Haven on March 27 at the age of 84. The core of his devoted student following grew from courses in the Directed Studies program and his yearlong Studies in Grand Strategy seminar, which he co-taught with historians John Gaddis and Paul Kennedy. But in the time between his arrival at Yale in 1992 and his retirement last year, he also taught courses ranging from The Architecture of Power and Baseball as Grand Strategy to Oratory in Statecraft, Tibet: An Enduring Civilization, and The Idea of Freedom.

“He loved being interdisciplinary, and the idea of interdisciplinary students serving as translators between fields,” remembers Tessa Murthy ’19, who worked as a research assistant for Hill. “I have a degree in mathematics; naturally, Professor Hill wanted me to learn Greek to translate Plato’s mathematical dialogues.”

His eclectic, adventurous approach to teaching mirrored his career before Yale. Hill was no ordinary academic, but a diplomat who served in the Foreign Service for nearly three decades. His first post was in Zurich in 1963, and later duties took him all over the world. In Hong Kong, he spent days scanning communist propaganda for clues to Beijing’s internal politics while devoting his nights to reading anything about China that he could get his hands on, from ancient poetry to modern Chinese history.

He brought this omnivorous approach to postings in South Vietnam, Israel, and Washington, where he served as a speechwriter and adviser for secretary of state Henry Kissinger and, later, top aide to secretary of state George Schultz. From 1992 to 1996, he played a similar role in the office of Boutros Boutros-Ghali, secretary general of the United Nations.

During this time he began teaching at Yale, where he was diplomat-in-residence in international security studies and Brady-Johnson Distinguished Fellow in Grand Strategy. Kissinger, who delivered the eulogy at Hill’s funeral by video, recalled sitting in on one of his classes: the seminar “was conducted as a dialogue on how to read, even more than what to read,” he said. Hill developed a reputation for iconoclastic opinions, mesmerizing chalkboard diagrams, and, underneath his reserved demeanor, a relentless devotion to his students.

“It was the understanding that Hill knew something about life outside the classroom that led me to call him in tears, years after I graduated, at a moment of real personal and professional crisis,” recalled Eliana Johnson ’06. “I hadn’t actually conceived of myself as strong or resilient before that conversation, but I have since.”

Hill is survived by his wife, Norma Thompson, a senior lecturer in humanities at Yale; his daughter Catharine L. Smith, and two grandchildren.

loading

loading