Aad Goudappel

Aad Goudappel

Illustration: Aad Goudappel

Illustration: Aad Goudappel

It’s not easy to name a university capital campaign. You want something that will tell donors that this is something special—not business as usual. But the name must also be broad enough to ensure donors that their interests and priorities are part of the campaign. When Yale launched a $1.5 billion campaign in 1992, the university was in the midst of a budget crisis and was dealing with the consequences of decades of deferred maintenance on its buildings. That campaign was titled “. . . and for Yale,” a reminder that not only God and country required donors’ attention.

By 2006, the university was on much sounder financial footing (thanks not only to fundraising but also to extraordinary returns on the endowment). Donors were encouraged to look to the university’s future and aim to meet the $3.5 billion goal of the campaign known as “Yale Tomorrow.”

Things again look different in 2021. Yale and its peers are sometimes criticized for having too much money, and that money has already brought extraordinary improvements to the university’s campus and programs. At the same time, the nation and the world have been through the wringer: a prolonged and deadly pandemic; difficult reckonings with racism, wealth inequality, sexual misconduct, and political extremism; and the mushrooming catastrophe of climate change. In the midst of all that, an appeal to alumni and philanthropists to help make Yale richer doesn’t quite feel on point.

So when the university went public with its new five-year, $7 billion campaign in an online event on October 4, the name announced for the campaign—“For Humanity”—reflected a different approach. This campaign will be built around the idea that money given to Yale will be put to work to solve those problems that are keeping us up at night. “This campaign is not about giving to Yale for Yale’s sake,” said campaign cochair Donna Dubinsky ’77 at the launch event. “Yes, we’ll build buildings, we’ll endow professorships, we’ll support students. But that’s not really the point. The point of this campaign is to make change in the world.”

To that end, the launch featured films and discussions that emphasized areas where Yale can make and has made a difference: not only the response to COVID-19 by the university’s medical and public health researchers, but also work on climate change, equity in policing, cancer treatment, and other areas. Conspicuously missing were the traditional honey-toned appeals to alums to remember their “bright college years” and give out of loyalty and gratitude.

That’s not unusual these days. Donors of all kinds—not just in higher education—are driven less by the strength of affiliation and more by an interest in investing their charitable dollars effectively. “For universities, the clear message from donors is: ‘What’s the impact of my gift and how does it match what I hope to achieve?’” says Linda Durant, a veteran fundraiser and former vice president of development at the Council for the Advancement and Support of Education.

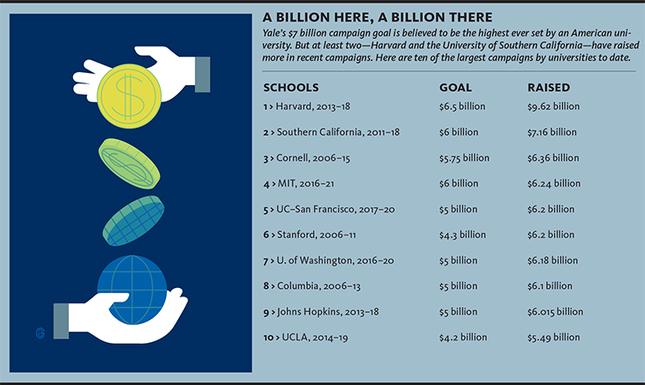

Like nearly all big capital campaigns, this one actually began its “quiet phase” three years ago, when Yale’s development staff and volunteers began making their pitch to major donors. At first, there were in-person panels and visits, where faculty talked to donors about their work; once the pandemic started, such meetings became virtual. The efforts were fruitful, yielding $3.5 billion in commitments by the time of last month’s launch. That success led organizers to commit to a $7 billion goal—believed to be the largest target ever set for a university capital campaign. (Harvard raised $9.62 billion in its campaign ending in 2018; its goal had been $6.5 billion.)

That number may sound enormous, but when you look at what Yale raises in a given year when it’s not in a campaign, it’s less daunting. From 2011 (when the Yale Tomorrow campaign ended) to 2018 (when the new campaign got off the ground), the university averaged $555 million per year in gifts. And all gifts to the Alumni Fund, and other annual gifts from 2018 to the end of the campaign in 2026, will be counted toward the campaign goal.

Some recent high-profile gifts are included in the $3.5 billion already raised, among them David Geffen’s $150 million gift to eliminate tuition at the drama school, which now bears his name; a $100 million donation from FedEx to fund the new Center for Natural Carbon Capture; the $150 million gift from Stephen Schwarzman ’69 to create the Schwarzman Center; $100 million of the $160 million gift from Edward Bass ’68 toward the renovation and expansion of the Peabody Museum; and an undisclosed large gift from Joseph C. Tsai ’86, ’90JD, and his wife, Clara Wu Tsai, to create a neuroscience institute.

With half the goal reached, the university launched its public campaign with the October event—originally planned for October 2020 but postponed twice amid uncertainty about COVID. There had been hopes that Yale could host a large in-person event in Commons that would be broadcast online. But campus visitor policies didn’t permit in-person guests. The event was broadcast from Commons with only the principals there in person.

More than 5,400 people preregistered for the event. (At press time, the organizers didn’t have data on how many actually watched or participated in the interactive portions.) They saw films focusing on work being done at Yale, conversations between alumni and students about mutual areas of interest, faculty panel discussions, a cameo appearance by computer science grad student Matt Amodio—then in the middle of a long championship run on the game show Jeopardy!—and a concert by the a cappella group Pentatonix, which features Yale alum Kevin Olusola ’11. In another film, Angela Bassett ’80, ’83MFA, introduced the campaign theme, asking viewers to “tell me not what you’re against; instead, tell me what you’re for.” “What are you for?” became a kind of leitmotif for the launch.

While the event laid out the campaign’s case in a broad sweep, it didn’t include a lot of specifics about how exactly the money would be used. The campaign’s designers break down the larger theme “For Humanity” into four “pillars” or priority areas for the campaign: Arts and Humanities for Insight, Science for Breakthroughs, Collaborating for Impact, and Leaders for a Better World.

Together, the pillars cover pretty much anything Yale is looking to fund. “Leaders for a Better World” can include all kinds of efforts to recruit, educate, and train students to be leaders, from financial aid to athletics. “Collaborating for Impact” highlights Yale’s ongoing efforts throughout the university to work across disciplines on specific problems. “Science for Breakthroughs” covers the priorities identified in the 2018 science strategies report: integrative data science, quantum science, neuroscience, inflammation, and environmental and evolutionary sciences.

And “Arts and Humanities for Impact” includes pretty much anything that isn’t science.

Joan O’Neill, vice president for alumni affairs and development, cites some examples of fundraising objectives that align with the campaign’s priorities: raising a billion dollars or more to fund student financial aid and student support in all Yale’s schools; completing the fundraising to turn the Jackson Institute into the Jackson School of Global Affairs; endowing new and existing professorships, and endowing a new interdisciplinary institute to study inflammation and inflammatory diseases.

The campaign’s website, forhumanity.yale.edu, features a gift guide with suggestions sortable by schools and areas of interest. They range from a $25 donation to the Yale College Dean’s Safety Net fund, which helps students with emergency financial needs, to $100 million for the opportunity to name the recently completed Yale Science Building.

Although Yale has completed a staggering number of new building and renovation projects in recent years, there are some more in the works that are in search of gift funding. Most prominent among them are a new theater and headquarters for the David Geffen School of Drama, an ecologically sustainable “living village” that would house divinity students, a new physical sciences building on Science Hill, and an expansion of the swimming pool at Payne Whitney Gymnasium.

You can also get an existing building named for you or a loved one. Those opportunities are spelled out on the site as well: that Science Building for $100 million, for example—or, if that’s too rich for your blood, a stairwell landing in the School of Architecture’s Paul Rudolph Hall for $250,000. Because such projects have already been built and funded, the money would be designated elsewhere: in the case of the Science Building, to an endowment supporting research; for the stairwell, to a resource fund managed by the architecture dean.

In some ways, university fundraising today is a constant ongoing effort to solicit major gifts and to keep up participation among alumni. So what’s the point of a time-limited capital campaign? “This is when we look to engage the community in a broader way and when we get donors to put Yale at the front of the list,” says O’Neill. Besides generating a sense of urgency and excitement around giving during the campaign, development officials say, a successful campaign results in a lasting bump in levels of giving afterward.

But how important is the money collected from less well-heeled alumni, sometimes in two- or three-digit sums? Just as wealth inequality in America has become more extreme, so has the proportion of giving coming from the wealthiest donors. It’s a rule of thumb these days that 95 percent of the money given in higher education comes from 5 percent of the donors. And the proportion of alumni who donate to their alma maters has fallen off dramatically; at Yale it has dropped from 34.4 percent in 2000 to 18.4 percent in 2020. O’Neill says about 30 percent of alumni have given to the campaign so far.

Does a small donor’s gift make a difference? “I’m a million-dollar donor, and I ask myself that sometimes,” says Dubinsky, laughing. “But it’s a little like voting. You can say, ‘My vote doesn’t count,’ and in some sense maybe you’re right. But if everybody decides that, it counts a lot.”

O’Neill backs her up with some statistics. “Last year, the Alumni Fund raised over $40 million,” she says. “Thirty percent of those gifts were $50 or less. It really does take everybody.”

But O’Neill adds that it’s not all about the money. A capital campaign should also be a time to get alumni more involved, in all kinds of ways. “In this campaign, for the first time in Yale’s history,” she says, “we will be setting non-financial goals as well as financial goals.” These will revolve around recruiting alumni as mentors and volunteer leaders, especially among groups that may not have been as close to Yale in the past. “If in the end, we have just raised money, and we haven’t broadened the engagement of our alumni, we would say that we haven’t achieved our goals.”

In other words, alumni should expect to hear a lot from Yale and from their classmates and other volunteers over the next five years. And be ready—because they’ll probably be asking, “What are you for?”

loading

loading