Courtesy Harvard University

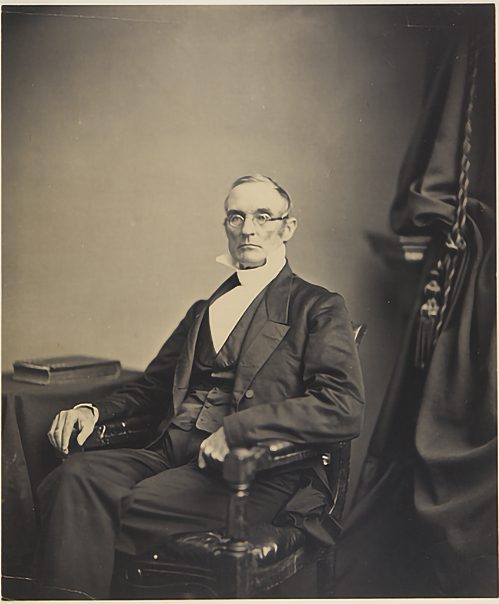

Joshua Leavitt, Class of 1814, sat for this portrait in the studio of Mathew B. Brady around 1860.

View full image

Courtesy Harvard University

Joshua Leavitt, Class of 1814, sat for this portrait in the studio of Mathew B. Brady around 1860.

View full image

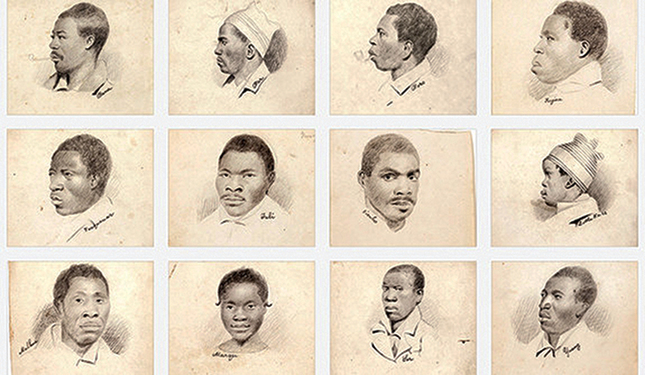

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Some of the sketches of the Amistad captives made by New Haven resident William H. Townsend during their detention in the city. Joshua Leavitt was among the three members of a committee that raised money for their defense and return to Africa.

View full image

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Some of the sketches of the Amistad captives made by New Haven resident William H. Townsend during their detention in the city. Joshua Leavitt was among the three members of a committee that raised money for their defense and return to Africa.

View full image

“We would say to all the friends of justice: remit no vigilance, slacken no effort, suspend no prayer, pass by no means that can aid in procuring justice, leave no stone unturned to save our country from the fearful degradation and guilt of shedding the blood of these unhappy men—and then hope for the best, and trust in God.”

These words, published in the pages of the antislavery newspaper The Emancipator on January 14, 1841, were a rallying cry on behalf of the mutineers from the slave ship Amistad who had been brought to New Haven in 1839, and whose case was about to be heard by the United States Supreme Court. They were written by Joshua Leavitt (1794–1873), who graduated from Yale College in 1814. Leavitt was one of the most prominent Yale and New Haven men who took leading roles in the abolition and antislavery movement, following several career paths in his lifetime dedication to the cause.

A native of Massachusetts, Leavitt entered Yale as a sophomore. After he graduated, he was awarded a Berkeley scholarship for informal graduate study at Yale. Then, after studying law at home, Leavitt was admitted to the bar in Northampton in 1819. In 1823, he returned to New Haven and enrolled in the first class in the newly organized Divinity School.

In 1825, Leavitt was installed as pastor of the congregational church in Stratford, Connecticut. He soon joined the new temperance movement and added to his duties those of agent of the American Temperance Society and the Seamen’s Friend Society in New York. Dismissed from his pastorate in 1828, Leavitt then took charge of the Sailor’s Magazine and thereafter worked primarily as an editor.

In 1831 Leavitt became the editor and proprietor of the New York Evangelist, a new organ devoted to liberal religious movements. When he lost ownership of the paper in the financial crisis of 1837, he was happy to be appointed editor of the weekly Emancipator, which was the official newspaper of the American Anti-Slavery Society. The society had been founded four years earlier by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan (a sometime New Haven resident who is buried in Grove Street Cemetery).

It was while Leavitt was editing the Emancipator that the Amistad case became a focal point for abolitionists. The story of how Joseph Cinqué and 52 other captives seized the ship that was transporting them into slavery, then were turned over to US authorities after running aground on Long Island, is a familiar one, memorialized in books, monuments, and in the 1997 Steven Spielberg film Amistad.

Because the captives were brought to the nearest US Marshall in New Haven, Yale and New Haven people became actively involved in their care and defense. New Haven attorney Roger Sherman Baldwin ’11 represented them in court. Divinity professor Josiah Willard Gibbs ’09 found a translator by searching the wharves of New York. Another divinity professor, George E. Day ’33, and his divinity students taught the Africans English and Christianity, as did local minister and abolitionist Leonard Bacon ’20.

For his part, Leavitt founded the Amistad Committee, mainly as a fund-raising effort, along with Simeon Jocelyn, a white former Yale divinity student who led a Black congregation in New Haven (and who had tried a few years earlier to start a Black college in the city—see page 46), and Lewis Tappan, a New York abolitionist and brother of Arthur Tappan.

In January 1840, at the district court in New Haven, Judge Andrew Judson declared that the Africans were innocent and should be returned to Africa. President Van Buren thought otherwise, favoring the Spanish claim that the captives were legal Cuban slaves and directing the US attorney for Connecticut to appeal the case to the Supreme Court.

In late February 1841, the Amistad case opened with former President John Quincy Adams heading the defense team. The attendees in the crowded courtroom included Francis Scott Key. On March 9, the Supreme Court ruled that the Africans were not legal slaves and had killed in self-defense. “It was the only instance in history where American Blacks, seized by slave dealers, won their freedom and returned home,” writes Howard Jones in his 1987 history Mutiny on the Amistad.

Two days after the decision, the Amistad Committee published a notice “to the Friends of the African Captives,” proudly proclaiming:

The committee have the high satisfaction of announcing that the Supreme Court of the United States have definitely decided that the long-imprisoned captives who were taken in the Amistad, ARE FREE, on this soil, without condition or restraint. . . . In view of this great deliverance, in which the lives and liberties of thirty-six fellow-men are secured, as well as many fundamental principles of law, justice, and human rights established, the committee respectfully request that public thanks be given on the occasion to Almighty God in all the churches throughout the land.

The Amistad Committee continued work to fund their journey home. In November 1841 the 35 surviving Africans departed from New York aboard the barque Gentleman for their voyage back to Africa.

Leavitt’s own beliefs varied according to the times: he had at different times advocated gradual emancipation, recolonization, and abolition. Often at variance with the uncompromising Garrison and his sympathizers, he moved from New York to Boston in 1842. In 1848 he became office editor of the Independent, continuing in a lesser position when he reached 70. He died in 1873, leaving among his survivors a son, William Solomon Leavitt ’40, ’43MA, who served as pastor in churches in Massachusetts and New York.

loading

loading