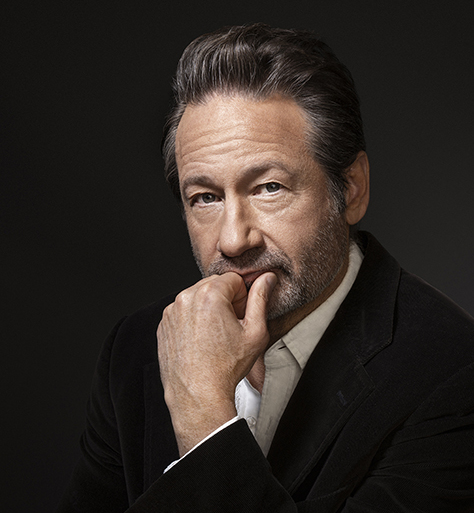

Michael Grecco

Michael Grecco

Brinson+Banks for the New York Times: Redux

Six years ago, David Duchovny ’89Grd and Gillian Anderson became Mulder and Scully once again, reprising their “X-Files” roles for six episodes. They’re shown here at the Hollywood Roosevelt hotel in Los Angeles in 2016.

View full image

Brinson+Banks for the New York Times: Redux

Six years ago, David Duchovny ’89Grd and Gillian Anderson became Mulder and Scully once again, reprising their “X-Files” roles for six episodes. They’re shown here at the Hollywood Roosevelt hotel in Los Angeles in 2016.

View full image

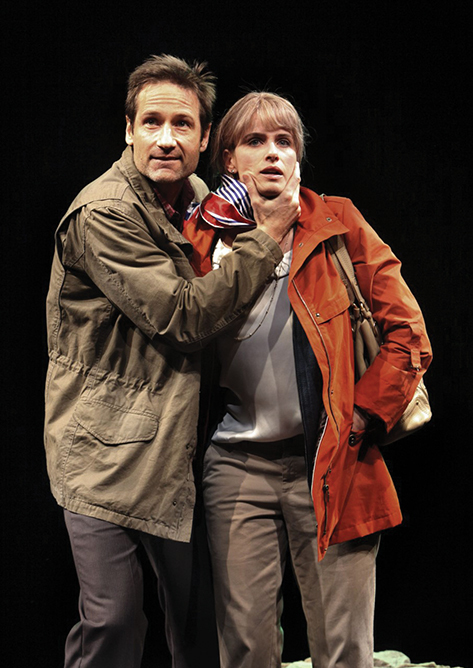

Sara Krulwich for the New York Times: Redux

In 2010, Duchovny played the only survivor of an office massacre in the play The Break of Noon. He’s shown here with actress Amanda Peet in the off-Broadway Lucille Lortel Theatre.

View full image

Sara Krulwich for the New York Times: Redux

In 2010, Duchovny played the only survivor of an office massacre in the play The Break of Noon. He’s shown here with actress Amanda Peet in the off-Broadway Lucille Lortel Theatre.

View full image

David Duchovny likes to tell the story about how one graduate school seminar at Yale changed his life. “Oh, it’s a good story—sad, funny, and absurd,” he assures the reader at the end of his latest novel, Truly Like Lightning. He described the pivotal moment recently in an essay in the Atlantic magazine:

When I was in grad school, my plan was to be a critic and professor and use the three summer months off every year to write. I was sitting in a seminar led by the legendary professor Harold Bloom, staring out the window at the winter dark descending (before 2 p.m., it would seem, just to fuck with your head) on an ever-gray New Haven. Bloom was asking a question I didn’t understand. No one answered until the lone undergraduate in the room, a precocious, genius young woman, said, “That would be like a world without adjectives.”

“Exactly, my dear,” Bloom chanted, “exactly.”

Duchovny, speaking to me on Skype from his home in Los Angeles, elaborates: “Graduate seminars can be pretty quiet, because grad students are supposed to know more than undergrads, so they tend not to speak up.” (His second novel, Bucky F*cking Dent, refers to “fifteen pimply grad students in New Haven sitting at a round table . . . and wondering about tenure.”) “Nobody spoke up, except for this terrific student. I didn’t understand the question and I didn’t understand her answer,” Duchovny says, “and I thought: perhaps I’m not in the right seat here.”

So, gradually, he switched seats. “I started hanging around the drama school and did a couple of plays. At Yale there are so many productions going on they just run out of bodies.” Pretty soon he was attending auditions in New York City, and the rest is small-screen history: after landing some minor movie and TV roles (“Tess’s Birthday Party Friend” in Working Girl; a cross-dressing* DEA agent on Twin Peaks), Duchovny achieved international fame as the costar of Fox television’s smash hit The X-Files, and later as the priapic novelist Hank Moody in the raunchy, brilliant Showtime series Californication.

But wait—who was the genius undergraduate who boldly ventured where the pimply grad students feared to tread? “I can’t tell you the name of the protagonist because she went on to become well known,” Duchovny says.

However, in a 1998 Playboy interview, Duchovny had identified the precocious undergraduate as Naomi Wolf ’84, by then a Rhodes Scholar and author of numerous books. In 2004, Wolf accused Bloom of a “sexual encroachment,” a charge he denied.

Duchovny arrived at Yale in the fall of 1983. He had considered applying to Berkeley as well, but his undergraduate mentors at Princeton, Maria DiBattista and David Bromwich ’73, ’77PhD (now Sterling Professor of English at Yale), lobbied for Yale. It was a storied time in the English department. “Paul Fry was a very popular teacher,” Duchovny says, “as well as John Hollander, Bloom, J. Hillis Miller, and Geoffrey Hartman, whom we of course called Geoffrey Hartman, Geoffrey Hartman”—a nod to the 1970s-era hit TV show Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman. “I had seminars with all of them.”

A Mellon Fellowship paid most of his bills, and, like many grad students, he occasionally taught undergraduates. Duchovny remembers TA-ing a course for Robert Stepto and Alan Trachtenberg, as well as a section of Daily Themes. “I taught Chang-Rae Lee,” the award-winning novelist and Stanford professor, Duchovny recalls. “I can’t claim to have influenced him positively or negatively.”

“David was of course a student favorite,” Lee ’87 remembers. “It was obvious he was the object of many student crushes, including my girlfriend’s! I admired him because he was quite different than the usual English grad student—very outgoing and cool, self-confident, and full of wit and candor.”

Lee’s Stanford colleague and Yale ’87 classmate, English professor Denise Gigante, also remembers Duchovny as a TA. “We weren’t sitting around a table; the students sat in exam chairs and David sometimes reclined like Venus on the desk in front of us. He was a rising star,” she continues. “There was never any doubt that he was extremely intelligent, and he knew it. I thought he was arrogant, but, you know, a lot of people with talent are.”

After passing his orals and choosing a subject for his dissertation—“Magic and Technology in Contemporary American Fiction and Poetry”—Duchovny drifted away from the English program to pursue acting. “I might still be there,” he says. “I’m not sure I ever officially resigned.”

In a sense, he did come back. In 2015, Duchovny published his first novel, Holy Cow, a short, light satire that might pass for a distant cousin of Animal Farm. “Writing was something I should have been doing for a long time,” he says. “I felt like a beginner in some ways, but I also felt that I had so much saved up in me. I had written so much nonfiction at Princeton and Yale.”

His writing has improved with each book. His second novel, Bucky F*cking Dent, reads like a classic first novel, full of energy and profound (if rough-hewn) themes: in this case, an end-of-life father-and-son reunion, told against the backdrop of the legendary finish of the 1978 American League baseball season, Boston Red Sox v. New York Yankees. A season rescued or ruined, depending on whom you root for, by one Bucky F*cking Dent.

The grad student returned in full flower in Duchovny’s third novel, Miss Subways, inspired by a Yale undergraduate production of the Yeats play The Only Jealousy of Emer. “A friend invited me to see it, and obviously it stuck with me forever,” he says. Miss Subways may be the most deviously titled novel in recent history (“a sensual, surreal comedy noir,” according to USA Today); it has very little to do with the Metropolitan Transporation Authority and a lot to do with magical realism and Irish mythology.

Subways has a boatload of clever writing, often inflected by two-plus years of English seminars. Case in point: Emer, a schoolteacher, ruminating on The Tempest: “Oh, that Billy Shakespeare, he got everywhere first, didn’t he? He took the virginity of the language itself, after Chaucer had bought her a few drinks.” Or: “As John Milton put it centuries ago in Areopagitica . . .”

Duchovny is a man who wasn’t nodding off during those “ever gray” New Haven seminars. In the Netflix series The Chair, Sandra Oh, who plays a beleaguered English department chair, hears Duchovny play the song “Mind of Winter,” from his real-life album Gestureland. “That’s the only rock song I’ve heard that references Wallace Stevens,” she notes. (Stevens’s poem “The Snow Man” begins: “One must have a mind of winter.”) A Spin magazine writer praised Gestureland, Duchovny’s third album, calling him a “Renaissance man.”

“I’ve been called worse,” Duchovny replied. “I like the Renaissance as much as anybody else.”

In The Chair, a comedy set in the fictional Pembroke University, Duchovny is being considered for a Distinguished Lectureship appointment. By way of promoting Duchovny to the skeptical department chair Oh, one of his boosters asserts: “He was Harold Bloom’s advisee.”

“No, I never was,” Duchovny says. “That was just [Chair cocreator] Amanda Peet being funny.” But he was enrolled in the life-changing seminar on Romantic poetry with Bloom, who would much later tell the Hartford Courant, “I remember him as a pleasant young man.”

Duchovny rarely misses a chance to praise Bloom, whom he described as “literary consciousness incarnate” to Michael Silverblatt, the host of Public Radio’s Bookworm show. “His mind was like a flashlight, pointing in certain directions. You would go where that beam led, and you’d find sustenance at those places—intellectual and spiritual sustenance.”

Bloom’s metaphorical flashlight pointed Duchovny to his latest and best novel, Truly Like Lightning, which might be loosely described as a latter-day Mormon epic. “I came upon Bloom’s 1992 work, The American Religion, in which he professes something more than mere admiration for [Mormon prophet] Joseph Smith,” Duchovny wrote in the Acknowledgements to Lightning. “He saw genius in him.”

“It’s like when a critic flexes their muscles to the utmost and they hold up a lesser artist, and they unearth the gold that they never spun,” Duchovny told me. “I took away this idea of genius, of American, Emersonian genius, and then the swerve—Bloom word—into religion, into a unifying principle of living.”

Writing in the Washington Post, critic Mark Athitakis called Lightning “the best of the batch, and makes a solid case for [Duchovny] as a real-deal novelist.” Duchovny’s editor, Jonathan Galassi, chair of the publishing house Farrar, Straus and Giroux, notes that unlike Duchovny’s three previous novels, Lightning didn’t originate as a screenplay. “It was conceived as a fiction by itself, and that’s why it draws on a different kind of imagination. It was a much more ambitious and original book,” Galassi says. “I think he’s getting better and better as a writer.”

What’s next? There is talk of making a Truly Like Lightning miniseries, and Duchovny plans to publish a novella, The Reservoir, in June of this year. “It’s almost like I needed to cleanse the palate,” he says. At age 61, Duchovny has earned a desirable, and threatening, status in American letters: a writer of great promise. “Lightning was my epic,” he says. “I don’t know if I have another epic in me. I never knew that I had a story like that in me, and now that I’ve done it, I want to try to do it again.”

___________________________________________________________________

* Editors’ note: The print version of this article and the original online version used an outdated term for cross-dressing that many consider offensive. We’re sorry for the mistake.

loading

loading

2 comments

-

Melanie Thomas, 6:40am February 25 2022 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Joan Diego, 11:16am February 25 2022 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.Lovely interview. So when does David get his honorary PhD? All those books certainly replace that unfinished dissertation.

I loved this interview. I especially enjoyed his peers’ assessment of him and Harold Bloom’s comment.

It was interesting to see reactions to David’s books. I love him as a writer and have enjoyed all four of his novels and his novella. I agree that Truly Like Lightning is his Masterpiece so far. The pictures posted were wonderful!