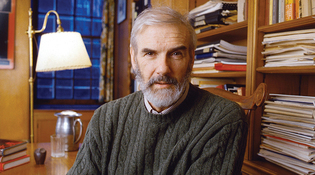

Michael Marsland

Sterling Professor of History Jonathan Spence ’65PhD taught Chinese history to generations of Yale students.

View full image

In a work of characteristic brilliance, Jonathan Dermot Spence ’65PhD brought to life a woman murdered more than 300 years ago. The pioneering historian of China wrote 14 books that examined figures ranging from the Kangxi emperor to Mao Zedong himself, but his genius for detail was most on display in the stories he told about forgotten people, like the title character in The Death of Woman Wang, who was killed by her husband and left lying in the snow one night in a remote backwater of Shandong Province.

The tale’s climax comes after a slow buildup that lays the groundwork for the reader to understand life in that specific place and time—the floods, the tax collectors, the despair of farmers, the fates of widows. “Jonathan simply sees what most of us overlook,” wrote Frederic E. Wakeman Jr., a distinguished professor of Chinese history at UC–Berkeley. Spence’s combination of meticulous archival research with sensitivity and warmth made him a remarkable teacher and scholar. He died on December 25 at his home in West Haven. He was 85 years old.

Spence was born in Surrey, England, in 1936. He came to the study of China after receiving his BA from Clare College at the University of Cambridge. During a Mellon Fellowship at Yale, he met historian of China Mary Clabaugh Wright and was inspired by her to study the Qing, China’s last dynasty. He had just joined the Yale faculty in 1966 when his first book, Ts’ao Yin and the K’ang-hsi Emperor: Bondservant and Master, brought him to the attention of China scholars around the world. Drawing on secret documents preserved in the National Palace Museum in Taiwan, Spence used the emperor’s own words to explore his world and that of Ts’ao Yin, grandfather of the author of The Dream of the Red Chamber, the preeminent Chinese classic.

The Death of Woman Wang followed, as did many other books, notably The Search for Modern China, based on Spence’s extremely popular History of Modern China lecture course at Yale. There he enthralled generations of undergraduates with court intrigues, crop failures, and the details of private lives long since extinguished.

Spence’s approach to history matched his approach to others around him. Tina Lu, Trumbull Professor of East Asian Languages and Literatures, recalls a conference his former students had held for him. Spence, overwhelmed with joy, made the gathering not about himself, but about them. Says Lu, “He was intensely aware of other people and other minds.”

loading

loading