Jeanine Dunn

When Yale announced in October that its endowment had grown by $11.1 billion in 2020–21, many people wondered what the university was going to do with all that money. Although three-quarters of the endowment is restricted by donor agreements, the recent gains surely left some room for new initiatives.

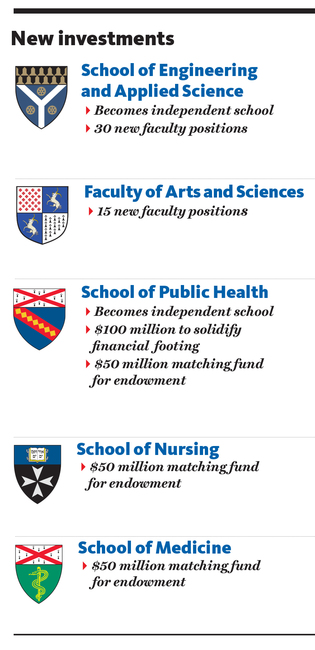

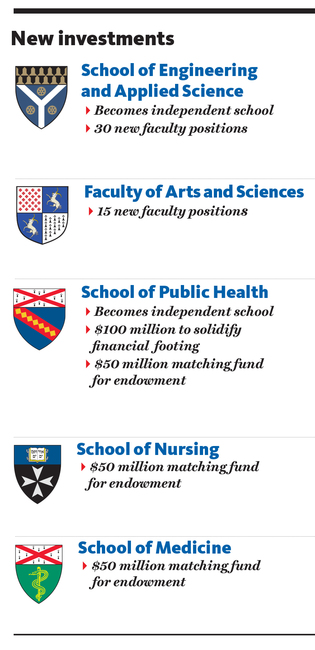

In a series of announcements in February, the university offered some answers: Yale will add 45 new faculty positions, restructure the School of Public Health and the School of Engineering and Applied Science as autonomous schools, build a new building and renovate others for science and engineering, and provide matching funds to increase the endowments of Yale’s three health-sciences schools. “Given the endowment returns and given the leadership opportunities, it feels like this is the right place to be making a major investment in the university,” says provost Scott Strobel.

Expanding engineering

Perhaps the most significant announcement was the creation of 30 new faculty positions in the School of Engineering and Applied Science (SEAS)—an increase of nearly a third from the current roster of 92. President Peter Salovey ’86PhD said in a statement that some of the new slots will go to computer science—currently the fourth most popular major in Yale College—and to materials science.

The expansion will happen under a new structural arrangement: on July 1, SEAS will become an autonomous school with its own faculty. Although it became a school in name in 2008, SEAS has been a division of Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS), the professors who teach in Yale College and the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Now, SEAS will have a distinct faculty and budget overseen by its dean, Jeffrey Brock ’92. Salovey and Strobel said in their announcement that the new arrangement “will allow SEAS to reimagine its culture, expand its research, and optimize its partnerships both within and outside Yale.”

The newly independent school will need a place to put all those new faculty and their labs. To that end, Yale is planning a new physical sciences and engineering building (known as the PSEB for now) at the north end of Science Hill. The structure, Strobel has said, is “likely to be the biggest capital project we have undertaken in Yale’s history.” The building will serve both SEAS and departments in FAS such as physics. The university also plans to renovate the engineering school’s older buildings on lower Hillhouse Avenue.

The expansion plans are a sign that engineering at Yale has come a long way since 1961, when an earlier School of Engineering was folded into FAS. In the early 1990s, when the university was facing a financial crisis, it seriously considered scaling back engineering further or eliminating it altogether. A long project of rebuilding has been under way since then, including the construction of the new Malone Engineering Center in 2005 and an expansion of the faculty authorized in 2008.

New faculty for FAS

In addition to the 30 new professors for SEAS, the university will fund 15 new faculty positions in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. About half of those will be in data-intensive social science, an area the university has identified as a priority; last fall, Yale announced the launch of the Data-Intensive Social Science Center to facilitate quantitative and empirical work in such fields as economics, political science, and psychology.

The number of FAS faculty—including SEAS—has hovered just under its target size of 700 for the last few years, after growing from around 600 in 2000 to around 700 in 2010. With the 45 new positions announced recently, Strobel says that the combined target faculty size for FAS and SEAS will be 750. Besides helping to meet specific academic priorities, the enlarged faculty also coincides with a recent 15 percent in enrollment in Yale College.

Independence for Public Health

No part of Yale has been more in the spotlight in the last two years than the School of Public Health (SPH), which has been in the thick of research and public messaging during the COVID-19 pandemic. Salovey and School of Medicine dean Nancy Brown ’81 mentioned both the pandemic and the need for public health leaders when they announced that the school will become “a self-supporting, independent school.” Since its founding in 1915, SPH had been a division of the medical school—the only nonautonomous school accredited by the Council on Education for Public Health.

The university is currently searching for a successor to the school’s dean, Sten Vermund, who is stepping down after five years. Salovey and Brown said that the new dean will lead the transition to the school’s independence. Since SPH currently runs a deficit and is subsidized by the medical school, the university is transferring $100 million to the SPH endowment to solidify its financial position.

SPH has grown quickly in the past few years: enrollment jumped from 393 in 2017–18 to 807 this year. The number of faculty increased from 125 to 154 in the same period. The school, now scattered in 12 buildings across the campus, would like to consolidate and improve its physical space; the announcement from Salovey and Brown says they will work with the new dean to “identify opportunities to improve the school’s facilities.”

A booster shot for health sciences

Yale also announced in February that it will match donations that SPH, the medical school, and the School of Nursing raise for their endowments over the next five years, up to $50 million per school. The promise that every donor’s gift will be doubled should help the schools raise money during Yale’s five-year “For Humanity” capital campaign. Strobel says it is a critical time to support these schools. “We have just endured a pandemic that has put incredible strain on health care professionals—probably none more than nursing—and it’s made clear the need for public health professionals to provide guidance to our communities,” says Strobel. “We see this as a place that it’s critical that we invest.”

The medical school’s funds will be earmarked for instructional activities, such as teaching or financial aid. The nursing and public health funds will be used at the deans’ discretion. Increasing financial aid and reducing student debt in the professional schools has been a goal for the university in recent years, and Salovey and Strobel say these endowment funds might help meet that goal. “The distribution from these endowed funds will enhance scholarships,” their statement says, “and thereby increase access to Yale’s three professional schools focused on improving health, fostering advancements in health equity, and enhancing the quality of health care for everyone.”

loading

loading