The Summer Friend

Charles Mcgrath ’68

Alfred A. Knopf, $25

Reviewed by Alex Beam ’75

Among the many attractions of Charles McGrath’s wonderful memoir, The Summer Friend, is that it’s hard to categorize. The jacket copy reports truthfully that the book narrates McGrath’s unusually rich, later-in-life relationship with a fellow parent, sailor, pyromaniac—there is a whole chapter devoted to “Blowing Stuff Up”—and kindred spirit, who dies too young. But Summer Friend is much more. It’s about summer; it’s about death, and it’s about living with the evanescence of time.

The book is a full-throated argument for doing fun things for the sake of, well, having fun. When McGrath and his friend Chip Gillespie took up golf, people asked him: “Why would you want to do something like that?” McGrath answers: “Because we could, I guess.” McGrath and Gillespie even taught themselves the art of lobstering. Because they could, I guess.

The author certainly enjoyed summer when he was at Yale. He and his future wife, Nancy, broke into the Payne Whitney gym (more than once!), swam in the pool, and practiced rowing in the famous water-filled tanks. They sneaked into Branford College and downed sliced peaches from the dining hall storeroom. They even infiltrated the classics department library above Phelps Gate. “I trust that since then the Yale security people have tightened things up,” McGrath writes.

Throughout the book one encounters unexpected but brilliant allusions. In the chapter “Going to the Dump,” McGrath examines a variety of religious experiences: “I feel at the end of a dump run the way I used to feel when I was young and very religious and used to go to confession regularly. . . . Going to the dump delivers that same sense of purgation.”

This is not a morbid book; quite the opposite. Yet when McGrath tells the reader his own nickname, the one he used in his long career with the New Yorker and the New York Times, the reader feels an undercurrent. In chronicling the passing of his deceased friend, Chip McGrath is also writing about his own death, and our own deaths, in a life-affirming masterpiece.

Alex Beam ’75 is the author of American Crucifixion: The Murder of Joseph Smith and the Fate of the Mormon Church.

___________________________________________________________________

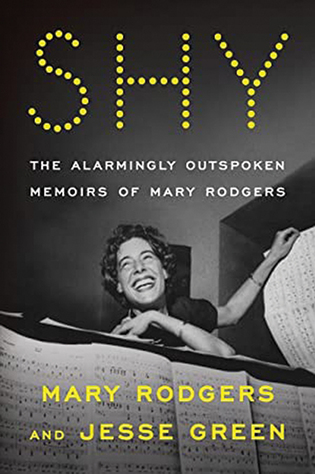

Shy: The Alarmingly Outspoken Memoirs of Mary Rodgers

Mary Rodgers and Jesse Green ’80

Farrar, Straus and

Giroux, $35

Reviewed by Mark Blankenship ’05MFA

Too much of Mary Rodgers’s legacy is focused on her relatives. Though she’s remembered for composing the Broadway musical Once Upon a Mattress and writing the young adult novel Freaky Friday, she’s more likely to be shorthanded as the daughter of legendary composer Richard Rodgers or perhaps the mother of Tony Award–winning composer Adam Guettel ’87. That could change, however, if enough people read Shy, a dazzling new memoir that foregrounds her as a witty, perceptive, and generous participant in America’s cultural history.

The book’s format allows her vitality to shine. Before she died in 2014, Rodgers sat with theater critic Jesse Green ’80 for years of frank interviews, and he has structured them with an ear for her conversational tone. She recalls everything from the parlor games she played with Stephen Sondheim to the harrowing morning she lost one of her children, and she expresses herself with the directness and élan of someone who spent her life commanding a room. She feels so alive and spontaneous on the page that readers may feel Rodgers is speaking directly to them.

Almost every paragraph has a footnote from Green, written in a similarly relaxed voice. When Rodgers mentions an obscure song, he is there to explain its provenance. When she insists an earthquake happened on a Wednesday, he notes, “Fine, but the earthquake occurred on a Friday.” This intertextual banter enhances the feeling that reading the book is like going to brunch with your most dazzling friends.

To that end, theater fans should savor Rodgers’s stories about the stars, directors, and writers she’d known from the day she was born. There are tales of shockingly bad behavior (including her own), as well as the nose-to-the-grindstone effort it takes to make a hit show. There are also countless examples of Rodgers’s willingness to help out, whether she was giving Sondheim advice on writing the musical Company or stepping up to be the chair of the Juilliard School. That enthusiasm for the world around her allowed her to experience enough for several lifetimes, and as this book proves, she knew just how to talk about what she’d seen.

Mark Blankenship ’05MFA is a critic and journalist who has contributed to the New York Times, NPR, and many others.

___________________________________________________________________

The Other Side of Prospect: A Story of Violence, Injustice and the American City

By Nicholas Dawidoff

W. W. Norton, $32.50

Reviewed by James Ledbetter ’86

In the early evening on August 1, 2006, a retired grandfather was killed by a single .45 caliber bullet to the neck as he sat in the driver’s seat of his cream-colored Chrysler 300, on a side street off Dixwell Avenue in New Haven. That murder alone could speak to the gun plague present in too many American cities, but what happened after is arguably worse. The seemingly obvious suspect was himself murdered before the month ended, yet authorities questioned an innocent 16-year-old boy without his parents present, squeezed multiple, contradictory confessions out of him, and ultimately sentenced him to 38 years in prison.

From these grim realities, author Nicholas Dawidoff spent years weaving a rich, sweeping tale of interlocking lives and tragic history. As with many Black families in Connecticut, the murder victim, Pete Fields, had come up from South Carolina during the Great Migration, seeking job opportunities. In Connecticut, one big draw was well-paying jobs in gun factories like Colt and Winchester. But the guns ended up staying around longer than the jobs.

Dawidoff’s narrative skill is at times so seductive that readers might be lulled out of their natural sense of outrage. It never became clear what made police detectives focus intently on Bobby Johnson as their suspect; he had no history with guns, and a palm print left on Fields’s car door was not his. In the end, Johnson was exonerated and compensated by Connecticut, giving the book a much-needed hopeful trajectory. But ultimately Dawidoff, a New Haven native, is taking aim at economics and weapons as the worst villains.

James Ledbetter ’86 is executive editor of the Observer.

loading

loading