Photograph by Bob Handelman

Photograph by Bob Handelman

Yale University Art Gallery

The Yale Athena in the Art Gallery sculpture hall in the 1930s, with the head of Juno still attached.

View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

The Yale Athena in the Art Gallery sculpture hall in the 1930s, with the head of Juno still attached.

View full image

Jean-Pol Grandmont

The Louvre’s Velletri Athena. Scholars believe the Yale Athena looked like this originally.

View full image

Jean-Pol Grandmont

The Louvre’s Velletri Athena. Scholars believe the Yale Athena looked like this originally.

View full image

Bob Handelman

The Yale Athena today in the Art Gallery sculpture hall.

View full image

Bob Handelman

The Yale Athena today in the Art Gallery sculpture hall.

View full image

Yale University Art Gallery.

In the 1930s, art students dressed Athena up for the Beaux Arts Ball.

View full image

Yale University Art Gallery.

In the 1930s, art students dressed Athena up for the Beaux Arts Ball.

View full image

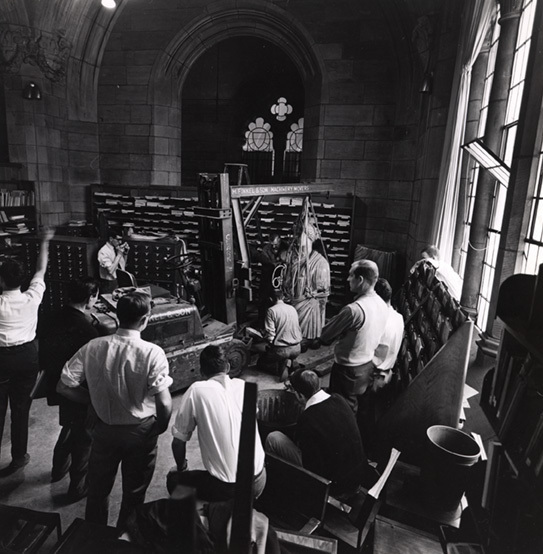

Manuscripts and Arrchives

Athena packed for its 1963 move from the Art Gallery to the new Art and Architecture Building.

View full image

Manuscripts and Arrchives

Athena packed for its 1963 move from the Art Gallery to the new Art and Architecture Building.

View full image

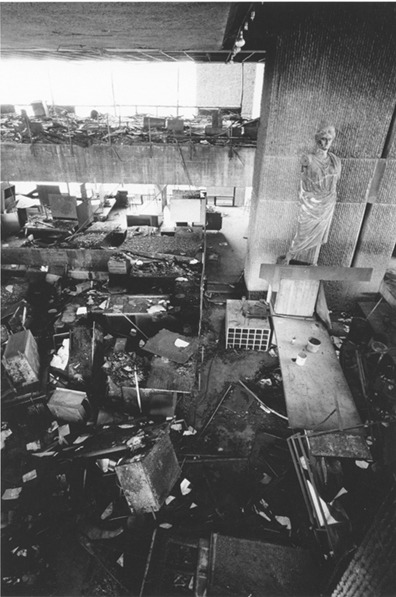

Manuscripts and Archives

Minerva, as she is known at the architecture school, stood amid the damage after a 1969 fire.

View full image

Manuscripts and Archives

Minerva, as she is known at the architecture school, stood amid the damage after a 1969 fire.

View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

Athena airborne after being removed through a skylight from the Art & Architecture Building, 1975.

View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

Athena airborne after being removed through a skylight from the Art & Architecture Building, 1975.

View full image

Bob Handelman

Today, a reproduction of the original statue watches over all-nighters and badminton games in the architecture school.

View full image

Bob Handelman

Today, a reproduction of the original statue watches over all-nighters and badminton games in the architecture school.

View full image

On June 25, 1975, for just a few minutes, Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom, warfare, and handicraft, soared high above the intersection of Chapel and York streets in New Haven.

It was just one remarkable episode in the life of a ten-foot marble statue that has been beheaded (twice), damaged in a fire, and subjected to all manner of abuse over its 1,800-year history. To its caretakers at the Yale University Art Gallery, it is a significant Roman copy of a lost Greek bronze statue of Athena from the fifth century BCE. But to students, faculty, and alumni of the School of Architecture, she is known by her Roman name—Minerva—as the muse and household goddess of the school’s graduate studios in Paul Rudolph Hall.

“Her presence is a calming constant for us, and I am convinced she brings us wisdom and insight,” says Deborah Berke, dean of the architecture school since 2016. But the Minerva that now watches silently over frenzied all-nighters, contentious final reviews, and twice-yearly badminton tournaments is not the same one that stood in the space from 1963 to 1975. Maybe we’d better start from the beginning.

Around 1870, a wealthy banker named Luther Kountze, who had moved east to New York from Denver just a few years before, brought home from Italy an armless marble sculpture that the Kountzes called Juno. When he built his estate a few years later, in Morristown, New Jersey, he installed the sculpture atop a 20-foot column near the main house. No record has been found of where and how Kountze acquired the statue. Susan Matheson, the curator of ancient art at the Art Gallery, says collectors typically looked to consultants or guidebooks to help them find dealers in Rome. “It was a thriving market,” says Matheson, and one still unencumbered by laws to keep such artifacts from leaving the country.

Luther Kountze died in 1918. His heirs sold the New Jersey estate, and in 1925 it came into the hands of an abbey of Benedictine monks. The statue remained atop her perch in New Jersey until 1928, when the monks decided to replace the pagan Juno with a statue of St. Benedict. Kountze’s son deLancey Kountze, Class of 1899, gave Juno to the Yale Art Gallery, which happily installed it in the sculpture hall of its new building.*

Upon the sculpture’s arrival at Yale, art history professor Paul V. C. Baur recognized its body as a depiction of Athena, similar to one in the Louvre known as the Velletri Athena. In a press release, the gallery dubbed her the Yale Athena. Both the Yale and the Velletri Athenas are thought to be Roman copies of a Greek bronze sculpture now known only from contemporary descriptions; scholars believe the lost original was by the noted Greek sculptor Kresilas. The head of the Yale Athena, Baur determined, was in fact Juno’s (Hera’s, in Greek mythology), and it was not the sculpture’s original head. Like the Velletri Athena, Yale’s Athena had probably worn a helmet and held a spear and a ritual offering dish.

Matheson says mixing and matching parts of ancient sculptures to make a more appealing package for sale was not uncommon in the nineteenth century. “You can just imagine: these dealers have crates of body parts,” she says. “So if there’s a stray head that would fit on top a body, you could put those together and that could work perfectly well. And nobody really cared. A body with a head on it sells for more money than a body without a head.”

And Yale’s Athena, it turned out, was a kind of ancient Mr. Potato Head: besides having the wrong head on her famous body, she had a nose salvaged from another ancient sculpture and a hair bun from yet another.

Papers in the Art Gallery’s archives show that Theodore Sizer, an art history professor and associate director at the gallery (he later became its director), was eager to restore Athena’s appearance to match its relative in the Louvre. In a 1931 letter to Kountze, he explained his plan to obtain plaster casts of the Velletri Athena’s head and arms and attach them to the Yale Athena. “The Juno head is much too large in proportion and detracts greatly, I think, from the beauty of the figure,” he wrote. Kountze was skeptical; he wrote in reply that several people he spoke to advised against it, and that “maybe the best thing to do would be to leave the old lady as she is after you have decapitated her.”

For whatever reason, the plan never came to fruition, and Athena kept Juno’s head for the time being. Soon, she became an object of fun: in 1937, Sizer sent Kountze a photo of the statue dressed up for the art school’s Beaux Arts Ball. “Certain liberties were taken with your Athena as you will see from the photograph that I am sending. . . . You will be happy to know that she is none the worse for wear.”

Thus began a decades-long tradition of irreverence toward the statue, an attitude that may also help to explain why, in 1963, the Art Gallery agreed to let architecture chair Paul Rudolph install the Athena in the new building he was designing for the School of Art and Architecture.

As Rudolph told the story in a 1978 interview, he learned that the Art Gallery had a collection of plaster casts of ancient Egyptian bas reliefs and Greek friezes in its basement. Some, he said, were still in their original unopened packing crates. He decided they would make good teaching tools in his building, and he got permission to install them.

He also decided he wanted Athena to stand in the large, two-story space where his architecture students would have their studios. “I just thought she was just splendid,” he recalled, but the gallery officials “didn’t think she was a very nice girl, . . . and when I broached the subject, to my complete surprise they were happy to get rid of her.”

From the time he requested the statue from the Art Gallery, Rudolph referred to her as Minerva—the Roman equivalent of Athena—and on the architecture school side of York Street, that is the name that stuck. Minerva appears frequently in statues on college campuses or on college seals because of her association with wisdom. But the symbolism of the statue was not foremost on Rudolph’s mind. “I didn’t care what it was, really,” he said. “I look at it not in terms of . . . her history. I look at her and her shape and size and color and texture and . . . whether she’s intrinsically right for that space.”

Raised on a block of concrete several feet off the ground—in an echo of Luther Kountze’s great column—Minerva made an impression on some of the students who worked in that space in the building’s early years. “I thought there was something very soothing about having it there,” says Turner Brooks ’65, ’70MArch, who teaches at the school today. Mark Simon ’72MArch considered her “a humanizing presence in what was for us an especially gritty space.”

Most students assumed that Minerva had been cast in plaster, like the other art seen around the building. So they did the kinds of things punchy students do: they put cigarettes in her mouth, painted her toenails, hung signs around her neck, adorned her with sunglasses, hats, or Christmas lights. “As students, we all believed it was just a plaster cast,” says John Jacobson ’70MArch, who has taught at the school since graduating and served for 22 years as an associate dean. “If we had known it was a real Roman piece of sculpture, we would have treated it with more respect.”

Minerva’s first reign over her new realm lasted less than six years. In 1969, an intense fire of unknown origin broke out in the architecture studio, causing significant damage to the building and necessitating a year’s worth of repairs. “A stately marble statue of the goddess Minerva presides over the charred rubble on the two floors of Yale’s School of Art and Architecture that were swept by a fire just before dawn on June 14,” the New York Times reported. “The statue, the only object of any consequence on the two floors that survived intact, is now doubly appropriate. Minerva was a goddess who both protected the arts and went to battle.”

But while Minerva was still standing, she was far from intact. She was blackened by smoke, and, more significantly, some of the marble in the folds of her gown flaked off from the effects of heat and water. She remained in the building after the fire, but her surroundings changed. As part of the post-fire renovations, there was a reshuffling of space in the building, and the painting students in the school’s art department were assigned to the fourth and fifth floors. They divided much of the open space into walled studios, and Minerva was no longer the center of attention.

Then, still desperate for studio space, the art department in 1975 decided to fill in some of the open area with an intermediate floor, including the spot where Minerva stood. Everyone agreed that it was time for her to go.

Susan Matheson had just started working at the Art Gallery at the time, and she was enthusiastic about reclaiming the sculpture. “My goal was to bring it back to the museum and to reintegrate it into what I hoped would be a growing collection of ancient art,” she says.

The problem was how to get the four-ton statue out of the building. The answer involved a very tall crane and a skylight. In an operation that made news around the country, Minerva was plucked from her pedestal, pulled up through the top of the building, and set down on a flatbed trailer on York Street for the short trip to the Art Gallery.

By 1975, museums had become more interested in authenticity for the presentation of ancient artifacts, so besides getting a good cleaning, Athena—as she is now again called by her Art Gallery caretakers—lost her head when she returned to the Art Gallery sculpture hall, where she is on permanent display. As for the head, it can be viewed by appointment at the Wurtele Study Center on the West Campus.

That’s more or less the happy ending for Athena. But she did have one more adventure. The School of Art and Architecture became two separate schools in 1972, and in 2000, the School of Art moved out of Rudolph’s building. And in 2008, a major renovation brought much of the architecture building back to its original appearance, including the fourth- and fifth-floor architecture studios.

John Jacobson, who was associate dean at the time of the renovation, saw an opportunity. “I kept saying ‘Minerva’s got to come back, and it’s got to come back exactly as it was.’” Persuading the Art Gallery to hand over the original sculpture once again was a nonstarter, but what if a copy could be made?

With great care and lots of insurance, the gallery packed up Athena and the head of Juno and sent them to Skylight Studios in Woburn, Massachusetts, where sculptor Robert Shure makes original works, does restorations, and creates reproductions of works of art. Shure made a mold from the pieces and cast a new Minerva in a polyester resin. (Shure says she weighs a “couple hundred pounds”—less than a hundredth of the marble original.)

Before the work was done, Shure called Jacobson with a proposition. Shure owns another studio that traces its origins to an Italian-American craftsman who, back in the early 1900s, had traveled to Europe and made molds directly from famous artworks in places like the Louvre and the British Museum. As it happened, Shure said, he had in his studio a cast of the head of the Velletri Athena—the very head that goes with the Yale Athena’s twin at the Louvre. If the school wanted, he could provide a new Minerva with something more like the head she would have had originally—fulfilling, in a way, Theodore Sizer’s scheme from 75 years before.

But Jacobson and Robert A. M. Stern ’65MArch, then the dean of the school, talked it over, and they concluded that Minerva ought to look the way she had when she had first been installed in the building. “We decided the wrong head was the right head in this case, given the history,” says Stern.

There was one last problem, though. When the new copy of Minerva was bought to the school and put on her pedestal, something didn’t look right to Jacobson. It was the nose—or, rather, the lack of a nose. Unbeknownst to Jacobson, the Art Gallery had removed the borrowed nose from the sculpture when they restored it in the 1970s, so the new reproduction was also noseless. Minerva would require some last-minute rhinoplasty.

“I said, ‘We’re gonna have to make a nose,’” Jacobson recalls. Shure climbed a ladder, sculpted a nose out of clay, and took it back to his studio to cast. He returning later, holding a nose. “If you look today, you’ll see that the color of the nose doesn’t quite match the sculpture,” says Jacobson. “But we have a nose.”

As in her previous tenure at the school, students today may take or leave Minerva. Some, as always, see her as a target for irreverence, and some pay her very little mind. But perhaps some with a soft spot for the classics look at her the way the late Doug Michels ’67MArch did. An architect and artist who cofounded the collective Ant Farm, he spoke about Minerva in a 1978 interview: he liked the idea “that there is this goddess whose function it is to take care of these things, and that she is there in this temple and there are people around, presumably under her graces. . . . I think one thing that Rudolph knew about was courting the muses.”

_________________________

* In our print edition and in an earlier online version of this article, we misidentified the town of Morristown as Morrisville, and we inaccurately referred to the abbey that bought the estate there as an order.

loading

loading

3 comments

-

David Decker, 11:11am January 12 2023 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Patrick, 10:28am January 13 2023 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Fr, Michael Tidd, O.S.B., 9:27am January 14 2023 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.As an Architecture student, I spent a few years in the shadow of the statue of Minerva, and I have many fond memories of working in the space she occupied.

Criticizing the building was in vogue then, but I always found the spaces to be inspiring.

In 1969, I was working for Charlie Moore, whose office was above the Bike shop on Chapel Street,

across from the A&A building. My desk was in the second floor window, facing the building,

When I arrived at work, I looked up I saw the broken windows and blackened concrete that was the aftermath of the fire.

I was very pleased in 2008, when the building was renovated to its original configurations.

My Class had its 50th reunion in 1969, and I was able to see the restored spaces.

I live in Denver, and the Kountze family and their descendants were, and are, family friends.

I have shared this Article with them.

David Decker, M Arch 1969.

Hello David,

thank you for sharing these insights & memories from Hamburg, Germany.

I am not a Yale alumnus, but I am a monk of the Benedictine abbey (not order), St, Mary's Abbey, in Morristown (not Morrisville) New Jersey that is the current owner of the former Kountze estate that was the home for Athena/Minerva. We own the remainder of Kountze's statue collection, mostly still in their original settings. Two of Kountze's statues (of Flora and Priapus) were identified in the late 1980s to be by Bernini, and are now found on display in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

We are presently researching how DeLancey Kountze was able to give to Yale a statue from his former family collection when the estate purchase by our community in 1925 included all of the statues in the estate's Italian Garden.