_2524x1402_0_948_645.jpeg)

Collage by Jeanine Dunn. Photo of Greene courtesy Lisa Senecal Moseley.

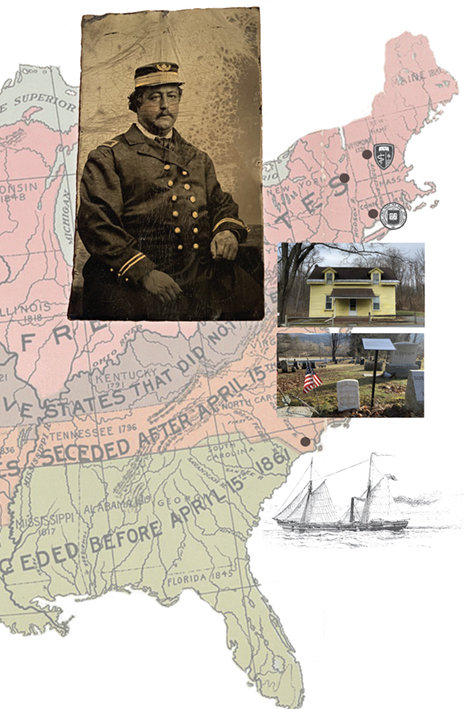

Richard Henry Greene, Class of 1857, wears his US Navy uniform from the Civil War in an undated tintype photo. The tintype is one of two that his great-great-granddaughter showed us.

View full image

_2524x1402_0_948_82.jpeg)

Collage by Jeanine Dunn. Photo of Greene courtesy Lisa Senecal Moseley.

Richard Henry Greene, Class of 1857, wears his US Navy uniform from the Civil War in an undated tintype photo. The tintype is one of two that his great-great-granddaughter showed us.

View full image

Collage by Jeanine Dunn. Photo of Greene courtesy Lisa Senecal Moseley.

Collage by Jeanine Dunn. Photo of Greene courtesy Lisa Senecal Moseley.

Nine years ago, a researcher at an auction house reminded Yale of a forgotten piece of its history: Yale College’s first Black graduate, Richard Henry Greene of the Class of 1857. We wrote about the rediscovery of Greene’s accomplishment at the time, but one thing was missing. We could find no pictures of Greene.

Now, we have a face to go with the name, thanks to Greene’s great-great-granddaughter, who recently shared with the Yale Alumni Magazine two tintype images of him in his Civil War uniform. (He was an assistant surgeon in the US Navy during the war.) They are the only known images of Greene. What’s more, Greene’s descendant is able to shed a bit more light on the life of this pathbreaking alumnus.

For years, Yale has celebrated the achievements of Edward Bouchet, a Black man who graduated from Yale College in 1874 and got his PhD from the university in 1876. He was the first African American to earn a doctorate from an American university. It was also sometimes reported—erroneously, it turns out—that Bouchet was the first Black graduate of the college.

But in 2014, Rick Stattler of Swann Auction Galleries revealed evidence that Greene held that distinction. Researching a cache of documents that the firm had acquired on consignment, mostly letters to and from Greene and other members of his family, Stattler found that census records and city directories in Greene’s hometown of New Haven identified him as Black, or sometimes “mulatto.”

Moreover, newspaper accounts of Bouchet’s graduation in 1874 mentioned that Greene had been the first Black graduate of Yale College. (Courtlandt Van Rensselaer Creed graduated from the School of Medicine in 1857, making him and Greene the first Black graduates of the university.) The documents Stattler studied are now in the Yale archives, a gift from the late William Reese ’77.

Lisa Senecal Moseley lives in Hoosick, New York, a small town just over the border from Bennington, Vermont. The house she grew up in, which she recently inherited from her mother, is the house where Greene and his family lived when he practiced medicine in Hoosick in the 1870s. It has stayed in the family for five generations.

Unlike Yale, Moseley had never forgotten Richard Henry Greene. He was remembered with reverence in the family. “I remember when I was little, I was fascinated by the books in a bookcase in the hallway. My grandmother would tell me, ‘Those are Dr. Greene’s medical books.’”

What neither Moseley nor her mother knew was that their ancestor was African American. The family identifies as white, and both Moseley and her mother were surprised when we approached them with the news that Greene was Yale’s first Black graduate. In retrospect, Moseley says, she remembers that as a girl she heard “the word ‘mulatto’ being tossed around—because that’s the word that was used then—and I didn’t know what they were talking about. I thought it was some kind of ice cream.”

As we reported back in 2014, it’s possible that Greene lived as a white man after his years at Yale. His wife, Charlotte (known as Lottie), was white, and in the 1870 census in Hoosick, he, too, is identified as white. This is not dispositive—census takers sometimes made their own assumptions when recording race—but there is no reference to his being Black in any of the scant published records about him in his years in the Navy or afterward. In the letters he wrote to Lottie while serving on ships in the Civil War, he never alluded to his race.

Coming from New Haven, where his bootmaker father was one of the founders of St. Luke’s, a historically Black Episcopal church, it would have been difficult for Greene to have been perceived as white at Yale, whatever his appearance. Like Edward Bouchet 17 years later, Greene lived at home in a Black neighborhood as an undergraduate. The only mention of him in the faculty minutes book refers to his having received “marks” for tardiness, which the faculty forgave because “he rooms at a distance from college.”

In his early life and at Yale, Greene spelled his surname without an “e” at the end. But by 1861, he had added the “e,” and thereafter he and his wife and daughter spelled their name that way. (We have adopted the spelling he preferred.)

After he graduated from Yale, Greene taught school, first in Milford, Connecticut, then at Bennington Seminary in Vermont. In Bennington, he apparently began his medical studies. In an 1863 letter of recommendation that resides in the Dartmouth medical school archives, Dr. B. F. Morgan of Bennington wrote that Greene had been studying medicine and surgery since March 1860.

Greene was writing to Lottie, then his fiancée, from medical school at Dartmouth by the fall of 1863. His letters reveal a sense of anxiety and responsibility about being a doctor: “I am studying all my strength will allow—from morning until late at night for I feel a great lack of acquirement,” he wrote on October 8, 1863. “It is necessary that I should improve very much to make a safe and reliable practitioner of Medicine.”

That sense of responsibility may have been heightened for Greene by the knowledge that his studies would soon be interrupted by the war; he had accepted a commission in the Navy as an assistant surgeon. By November, he had reported for duty in Philadelphia, where he was assigned to the USS State of Georgia. Over the next year and a half, on the Georgia and later the USS Seneca, he would be involved with a blockade in North Carolina, deal with outbreaks of yellow fever and smallpox, and go ashore at Norfolk, Virginia, after it was occupied by the Union. He wrote to Lottie about the feelings of the locals: “All the young men have gone out of the place with the Confederates and a kind of gloom hangs over the city. A good many of the secesh [Secessionist] ladies remain—they turn their heads when they meet any of our officers. . . . I really cannot conceive that we shall ever be a united people. Words can hardly express the bitterness of the Southerners toward the North.”

In the midst of his service, he received his MD from Dartmouth in 1864. In September of that year, he was able to get leave to marry Lottie in Bennington, her hometown. Despite his professional credentials, he was still unsure of his future, and in his letters to Lottie he considered teaching or the ministry as alternatives to medicine, taking care to manage her expectations: “If you are going to wait until I get rich you may have to wait forever. You knew when you accepted me you accepted a poor man who could not look forward in any way to a life of wealth and ease but to a life of labor and perhaps straitened circumstances.”

But after he returned from the war in 1865, he did settle into a career as a physician. Moseley says that he and Lottie first lived in Cambridge, New York, several miles northwest of Hoosick. She says he moved to Hoosick to help when there was an outbreak of cholera there, and then stayed there permanently with Lottie and their daughter Charlotte (also called Lottie) who was born in 1870.

Despite his fears, Greene seems to have been a respected physician in Hoosick. In a letter in the archives, a man in Harwinton, Connecticut, wrote to him that “I felt a confidence in you which I do not entertain toward any physician near us.” And an 1897 book about Rensselaer County remembered him as “fond of the study of natural history” and “a most amiable and genial man, and a practical Christian.” He was apparently an accomplished musician: in an 1862 letter, a Manchester, New Hampshire, man offered him a job as live-in music instructor for his daughter. Moseley says he played the organ at their local church. He passed this interest on to his daughter Lottie, who studied music in Philadelphia.

Greene died on March 23, 1877, at the age of 43. His father wrote to Yale that the cause was “disease of the heart.” Looking back, one might wonder if his health problems were an early example of what is known as “John Henryism,” a tendency for Black men to drive themselves especially hard in the face of discrimination, achieving success but at a cost to their health.

He was buried in a plot with some of his wife’s relatives at the Old Bennington Cemetery, where Robert Frost also reposes. Recently, after his distinction at Yale was rediscovered, the cemetery’s keepers put up a plaque with a short biography next to his military headstone.

Lisa Moseley says she and her mother were both “very pleased” to learn the rest of Greene’s story: “My mother said, ‘I always thought there was something different about me, and this fills in a lot of things.’” For example, Greene’s ancestry might explain the younger Lottie’s dark coloring and Moseley’s own olive complexion.

Moseley now owns Dr. Greene’s house, but she and her husband live in another house in the area. She hopes to open Greene’s house to visitors so they could see the parts that remain as they were when he lived there.

“I’m very proud to be this man’s great-great-granddaughter,” she says. “He overcame a lot of obstacles to make a valuable contribution to the world and to live as a ‘practical Christian.’”

loading

loading

8 comments

-

Konrad J Perlman, 10:20am February 23 2023 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

David zoncavage '70, 11:13am February 23 2023 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Christopher R. Cooke, class of 1965, 3:19pm February 23 2023 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Jane Siegel, '82, 12:44pm February 24 2023 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

James N. O'Connor, 1:27pm February 26 2023 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Mark Branch, 8:09am February 27 2023 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Verna Mae Pierce-Swift, 4:15am March 03 2023 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

-

Jill Newmark, 1:18pm March 07 2023 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.Great research about a very accomplished Yale graduate, who happened to be Black. Yale should be proud to call him one of our own.

Konrad Perlman, MCP '60

You are wrong. https://neveryetmelted.com/2011/05/17/yales-first-african-american-graduate/

Curious as to whether Richard Greene could be related to Belle da Costa Greene (1879-1950), a black woman who passed for white, was J. P. Morgan's personal librarian and ran the Morgan Library for 43 years. She is the subject of the recent book, "The Personal Librarian," by Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray.

Belle da Costa Greene's father is a different man (a Harvard man). Per the Morgan website, writing about Belle:

The daughter of Genevieve Ida Fleet Greener (1849–1941) and Richard T. Greener (1844–1922), Belle Greene (named Belle Marion Greener at birth) grew up in a predominantly African American community in Washington, DC. Her father was the first Black graduate of Harvard College and a prominent educator, diplomat, and racial justice activist. After Belle’s parents separated during her adolescence, Genevieve changed her surname and that of her children to Greene.

My classmate (Yale 56) and roommate for 4 years was Thomas A. Greene, whose family lived in New York City, and whose father was a re-insurance broker. Any relationship?

James O'Connor: Richard Henry Greene's only child was his daughter Lottie, so none of his descendants share his surname.

Fascinating! Wow! What an amazing story!

Great article! My new book Without Concealment, Without Compromise: The Courageous Lives of Black Civil War Surgeons will be published and available at the end of May 2023. It features a chapter on Richard H. Greene much of which is based on the archives at Yale.