National Portait Gallery

Samuel Seabury, seen here in a 1785 portrait by Ralph Earl, was a Loyalist who opposed American independence. But after the Revolution, he became the first bishop of the newly independent Episcopal Church.

View full image

National Portait Gallery

Samuel Seabury, seen here in a 1785 portrait by Ralph Earl, was a Loyalist who opposed American independence. But after the Revolution, he became the first bishop of the newly independent Episcopal Church.

View full image

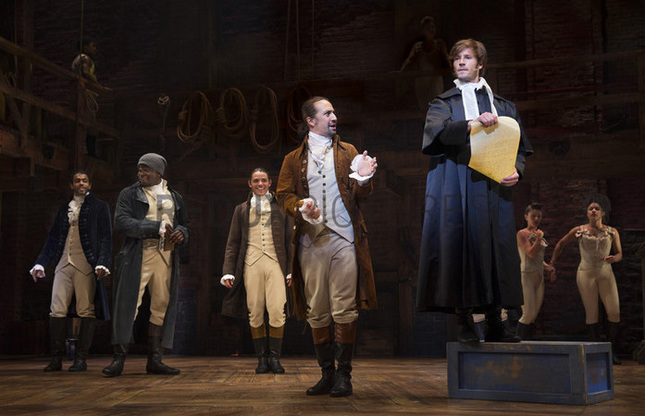

Sara Krulwich/The New York Times

In a 2015 performance of “Hamilton,” Samuel Seabury (Thayne Jasperson, right) is mocked by Alexander Hamilton (Lin-Manuel Miranda, center).

View full image

Sara Krulwich/The New York Times

In a 2015 performance of “Hamilton,” Samuel Seabury (Thayne Jasperson, right) is mocked by Alexander Hamilton (Lin-Manuel Miranda, center).

View full image

The good news for Samuel Seabury, Yale Class of 1748, is that more people have probably heard his name in the past eight years than in many decades before. The bad news: it’s because he’s mocked nightly in the long-running Broadway musical Hamilton.

Early in the show’s first act, Seabury, in an Anglican cleric’s robe, sings a prim Tory denunciation of the Continental Congress on the streets of Manhattan. “Heed not the rabble who scream ‘Revolution!’ They have not your interest at heart,” he intones, in a baroque style distinctly unlike the rest of the show’s pop- and hip-hop–inflected score. The scene is an excuse for young Alexander Hamilton to show off his debating chops. When Seabury repeats his verse, Hamilton talks over him using a kind of counterpoint that echoes Seabury’s words: “He’d have you all unravel at the sound of screams but the revolution is comin’ / The have-nots are gonna win this.”

The scene has its roots in historical fact: Hamilton and Seabury really did debate, but not face to face. Instead, they traded fiery pamphlets. Seabury, a Connecticut native, was the son of a Congregational minister who had converted to the Anglican faith; the younger Seabury was one of a small minority of Anglican students during his time at Yale. He became a priest himself, and he was serving in the New York village of Westchester (now part of the Bronx) in 1774 and 1775 when he wrote a series of Loyalist pamphlets under the pen name “A. W. Farmer” (i.e., A Westchester Farmer). “If I must be enslaved,” he wrote, “let it be by a King at least, and not by a parcel of lawless, upstart committee-men.”

Hamilton, a 17-year-old student at Kings College, responded with his own pamphlets. The title of the first one gives a sense of their tone: “A Full Vindication of the Measures of the Congress, From the Calumnies of their Enemies; in answer to a letter, under the signature of A. W. Farmer. Whereby his Sophistry is exposed, his Cavils confuted, his Artifices detected, and his Wit ridiculed.”

Whatever the merits of Seabury’s argument might have been, popular opinion was decidedly not on his side. In November 1775, he was arrested by rebels in Westchester and brought to New Haven, where he was paraded through the streets and held captive for six weeks before being allowed to leave. He found refuge in New York as chaplain to an American Loyalist regiment that was organized by another Yale graduate, Edmund Fanning ’57.

Seabury never appears again in Hamilton, but his real life had a remarkable second act. In 1783, ten of the few remaining Anglican priests in Connecticut gathered in Woodbury to consider the crisis brought about by the Revolution. Many priests and followers of the faith were Loyalists who had left the country once the British defeat was inevitable. And there was no church hierarchy: the colonies had never had their own bishop, which tradition required for church administration and the ordination of new priests.

For the church to continue in the new American nation, it would need the mother country to ordain an American bishop. The priests who assembled in Woodbury elected Seabury to go to England and seek ordination.

That turned out to be tricky. The English archbishops and Parliament were not quick to grant the Americans’ request, for a number of reasons. Perhaps most important, Parliament still required Anglican bishops and priests to swear an oath of allegiance to the king—a deal-breaker for Seabury and the American church.

After 16 months of negotiation, Seabury gave up on the English church and went to Scotland, where there were Anglican bishops who themselves refused allegiance to the House of Hanover. In 1784, three Scottish bishops consecrated Seabury, and he returned home as the first bishop in the United States.

Some Episcopal leaders, especially in New York and Pennsylvania, were unhappy about the consecration. They thought Connecticut had acted in haste, and they had problems with Seabury both in terms of his politics—some Episcopal clergy had been on the side of the Americans in the war—and his theology, which was seen as too nearly Catholic for a church that has always been pulled between Catholic and Protestant poles. It took several more years for Episcopalians in the former colonies to be truly united.

And the Congregationalists that ran Seabury’s alma mater? They were unimpressed. When it was suggested to Yale president Ezra Stiles that he give Bishop Seabury a seat at the dais at commencement in 1785, Stiles is said to have replied “We are all bishops here, but if there be room for another, he can occupy it.” Later generations at Yale were more receptive: one of the pavilions on the quadrangle of the Divinity School is named Seabury Hall in his honor.

Seabury oversaw the church in Connecticut and Rhode Island until his death in 1796. He was as forthright about his convictions in church matters as he had been in politics. His biographer Eben Edwards Beardsley wrote that he was “a man for the times, far-reaching in his views, of a bold and resolute spirit, who thought and spoke for himself and spoke what he thought.” When he could be heard over Alexander Hamilton, that is.

loading

loading