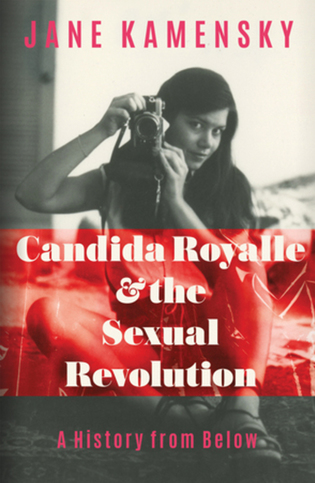

Candida Royalle and the Sexual Revolution

Jane Kamensky ’85, ’93PhD

W. W. Norton & Company, $35

Reviewed by Susan Burton ’95

In 2015, Jane Kamensky ’85, ’93PhD, a professor of history, began a new appointment at Harvard’s Schlesinger Library. For a certain kind of researcher, the Schlesinger is a ladies’ paradise. We come here to browse women’s lives. (I bet Émile Zola’s The Ladies’ Paradise surfaces because my introduction to the Schlesinger came through the papers of a department store buyer that I drew on for my senior essay.)

A few days into her new job, Kamensky read a New York Times obituary of a filmmaker and porn star named Candice Vadala—better known as Candida Royalle—who had just died at 64, of ovarian cancer. Vadala was an important figure in feminist porn, but if you can’t place her, it’s because she was literally hard to place: she didn’t fall neatly on either side of the usual divide. Kamensky immediately recognized the unique position Vadala had occupied, and wondered if she’d left papers.

It was a remarkable intuition. Vadala turned out to have been a self-archivist who for decades had documented her own life in diaries, drawings, and letters. Kamensky uses this trove in Candida Royalle and the Sexual Revolution to tell Vadala’s story, which she embeds in social, cultural, and political context.

Though Vadala’s life was marked by struggle, through it all she made art, including porn “from a woman’s point of view”—films that even today sound subtle and radical. And through it all she wanted to tell her own story. Even as she was dying, she was still imagining the pitch for her memoir.

Vadala had a conviction that her story mattered; Kamensky ratifies that. Toward the end of the book, she notes that Vadala’s papers are now available for perusal in the library. Her book invites reflection on not only feminism and sex, but on archives themselves: on the power of keeping them and of mining them, and on what drives us to tell the stories of our own lives and those of others.

Susan Burton ’95 is the author of a memoir, Empty, and creator of the podcast The Retrievals, for which she won a Peabody Award.

__________________________________________________________________

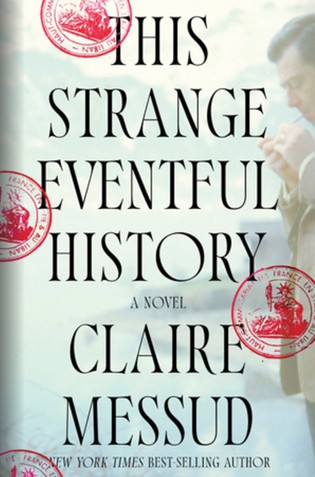

This Strange Eventful History

Claire Messud ’87

W. W. Norton & Company, $29.99

Reviewed by Rebecca Steinitz ’86

When Claire Messud ’87 was asked, at a recent event, if she ever considered writing her gorgeous new novel—This Strange Eventful History—as memoir, she responded, “No.” Though Messud has already plumbed her family’s past in fiction, The Last Life (1999) and A Dream Life (2021) are more evocative than documentary. This book, based on her grandfather’s handwritten family history, 1,500 pages long, gets down to brass facts. But fiction, Messud’s métier, allows her to go as deep and imaginatively into her family’s experiences as her own, embedding their collective story within the broad scope of political and intellectual history and a dense tapestry of vivid physical and emotional detail. The result is a splendid twenty-first-century rendition of a nineteenth-century literary stalwart: the realist novel.

The French-Algerian Cassars traverse the world in the decades before and after Algerian independence, grappling with the meaning of home, the nature of displacement, and the tension between a life of the mind and money. Righteous Gaston works his way from childhood poverty to comfort and success, powered by faith and transcendent love for his wife. François, Gaston’s bitter son, abandons graduate school for the corporate ladder and a passionately miserable marriage to his Canadian wife, the equally frustrated Barbara. Their daughter, Chloe, anxious and preternaturally observant as a child, achieves the literary life to which Gaston and François once aspired.

The book revisits the Cassars every decade or so from 1940 to 2010, marking the congruence between social change and their lives. Initially holding tight to their French identity in Algeria, they discover that France doesn’t want them, become cosmopolitan expats, and eventually reach the globalized turn of the century, with Gaston finally settled in France and his granddaughters fluently international.

Gaston’s authoritarian bent, François’s teenage depression and adult alcoholism, his sister Denise’s mental illness and romantic debacles, and their shared sense of shame may seem rooted in this peripatetic, othered history. But a final twist invites us to rethink everything we have read, deftly nudging the confident complexities of the novel’s realism toward the shaky ground of postmodernism.

Rebecca Steinitz ’86 is an education and communications consultant and the author of Time, Space, and Gender in the Nineteenth-Century British Diary.

___________________________________________________________________

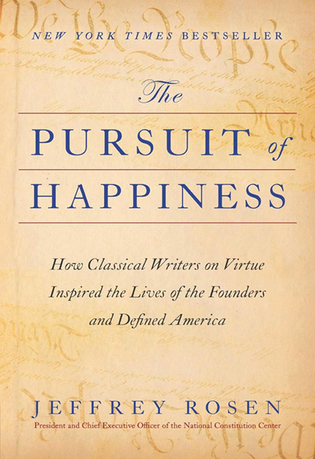

The Pursuit of Happiness: How Classical Writers on Virtue Inspired the Lives of the Founders and Defined America

Jeffrey Rosen ’91JD

Simon & Schuster, $28.99

Reviewed by David Greenberg ’90

As a writer for The New Republic, law professor, and CEO of the National Constitution Center, Jeffrey Rosen ’91JD has long been one of our foremost interpreters of constitutional law. His originality of thought and moderation of temperament are both on display in his new book, The Pursuit of Happiness.

Libraries teem with books about the Founders’ political thought. Rosen offers something different: an exploration of their moral philosophy. Although Adams, Frankin, Jefferson, and Madison disagreed about many things, they were children of the Enlightenment, steeped in the works of classical thinkers from Aristotle to Xenophon. Rosen, reading deeply in the ancient sages and the Founders themselves, seeks to understand what they meant by “the pursuit of happiness” and its place in their worldview.

In the Schoolhouse Rock cartoons, the pursuit of happiness was depicted by a man with outstretched arms chasing a woman through Independence Hall. Happiness, however, meant not sensory pleasure or short-term satisfaction but a life lived in accord with virtues like temperance, humility, and industry. Rosen shows how the Founders considered these virtues to be not only the pillars of a sound republican political order but the foundations of a good life—and cultivated them through their everyday routines. In short, Rosen gives us the Founders as self-help gurus, striving to comport themselves in keeping with venerable precepts. They did so in much the way that Rosen researched this book: through the purposeful study of our forebears’ wisdom. Amid our distracted, agitated lives, we could do worse than to follow suit.

David Greenberg ’90, a historian at Rutgers University, is the author, most recently, of Republic of Spin.

loading

loading