Courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

The Divinity School’s Living Village, at far right in this illustration, is under construction north of the Sterling Divinity Quadrangle, in a former parking lot.

View full image

Courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

The Divinity School’s Living Village, at far right in this illustration, is under construction north of the Sterling Divinity Quadrangle, in a former parking lot.

View full image

Courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

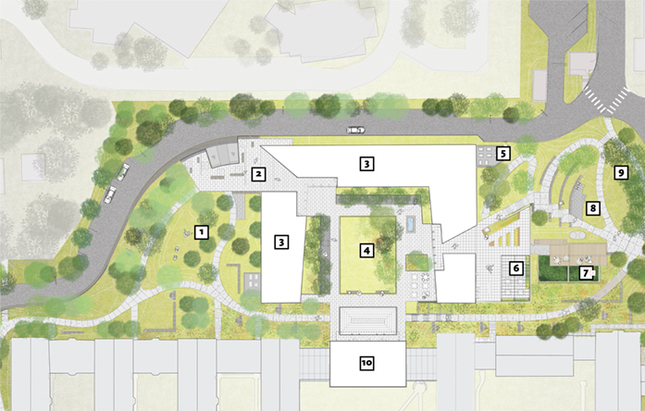

A site plan shows the arrangement of building and landscape in the Living Village. Just west of the building will be an orchard (1) with fruit- and nut-bearing trees. The main entrance portal (2) welcomes people from the orchard and Prospect Street. The residences (3) are arranged around a central courtyard (4). A village hub (5) will include a community patio and kitchen. Nearby will be a kitchen garden (6) and terrace with views of East Rock. Down the hill, a water garden (7) will make the water filtration process visible. A hillside amphitheater (8) will have seating for gatherings or performances. Fruit and berry bushes will be planted in a grove (9) at the east end of the site. A remodeled main entrance (10) to the Sterling Divinity Quadrangle connects the Living Village courtyard to the school’s existing buildings.

View full image

Courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

A site plan shows the arrangement of building and landscape in the Living Village. Just west of the building will be an orchard (1) with fruit- and nut-bearing trees. The main entrance portal (2) welcomes people from the orchard and Prospect Street. The residences (3) are arranged around a central courtyard (4). A village hub (5) will include a community patio and kitchen. Nearby will be a kitchen garden (6) and terrace with views of East Rock. Down the hill, a water garden (7) will make the water filtration process visible. A hillside amphitheater (8) will have seating for gatherings or performances. Fruit and berry bushes will be planted in a grove (9) at the east end of the site. A remodeled main entrance (10) to the Sterling Divinity Quadrangle connects the Living Village courtyard to the school’s existing buildings.

View full image

Courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

The scale of the courtyard allows for people to recognize faces from across its width.

View full image

Courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

The scale of the courtyard allows for people to recognize faces from across its width.

View full image

Courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

Generously sized common rooms encourage interaction and community building.

View full image

Courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

Generously sized common rooms encourage interaction and community building.

View full image

Courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

The corridors of the residences are visible through the glass walls facing the courtyard.

View full image

Courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

The corridors of the residences are visible through the glass walls facing the courtyard.

View full image

Courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

The terrace and kitchen garden east of the building will take advantage of the hilltop view of East Rock. Below the terrace will be an amphitheater. (The

hillside sloping down to St. Ronan Street will be preserved as a prime spot for sledding in winter.)

View full image

Courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

The terrace and kitchen garden east of the building will take advantage of the hilltop view of East Rock. Below the terrace will be an amphitheater. (The

hillside sloping down to St. Ronan Street will be preserved as a prime spot for sledding in winter.)

View full image

Courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

The water garden, where rainwater and waste water are filtered through a system that involves both wetland plants and mechanical components, is placed along a major circulation path to make people aware of the processes.

View full image

Courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

The water garden, where rainwater and waste water are filtered through a system that involves both wetland plants and mechanical components, is placed along a major circulation path to make people aware of the processes.

View full image

Courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

A community kitchen on the ground floor of the building opens onto a dining terrace. Shared meals will be an integral part of promoting community.

View full image

Courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

A community kitchen on the ground floor of the building opens onto a dining terrace. Shared meals will be an integral part of promoting community.

View full image

Courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

The main entrance portal draws people in from Prospect Street. The courtyard will have no gates, in order to send a message of inclusivity to the community.

View full image

Courtesy Bruner/Cott Architects

The main entrance portal draws people in from Prospect Street. The courtyard will have no gates, in order to send a message of inclusivity to the community.

View full image

Last summer, the divinity school broke ground for a new building just north of the iconic Sterling Divinity Quadrangle. The site: the school’s main parking lot. Workers got busy clearing the asphalt and preparing for the construction of a new 51-bed residence hall, the first new student housing at YDS since 1957. As Greg Sterling, the school’s dean, likes to put it, “You know the song ‘They paved paradise, and put up a parking lot’? Well, we unpaved a parking lot to put up paradise.”

You may be skeptical of the notion that any student housing could be paradise (a word that is laden with meaning at a divinity school, after all), but Sterling isn’t much exaggerating the scope of his dream for the project, which the school is calling the Living Village. Scheduled to open in the fall of 2025, the project is a statement that caring for creation should be a central part of religious faith.

Sterling says he wants the school to teach students that “they are part of a larger ecosystem, and that they have obligations to that larger system, not just to themselves and not only to other people.” He wants to create what he calls “apostles for the environment.”

The living village is designed to meet the standards of a certification program called the Living Building Challenge. Certification programs for sustainability are nothing new; Yale requires all of its projects to meet the standard for a Gold Level certification from the US Green Buildings Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program, which measures a building’s impact on the environment through such factors as its energy use, water efficiency, sourcing of materials, and embodied carbon. But the Living Building Challenge (LBC), based on principles developed by architect Jason McLennan, is more rigorous, holistic, and comprehensive. (McLennan worked with architects Bruner/Cott on the master plan for the Living Village and continues as an adviser to the project.)

In a TED Talk from 2015, McLennan appears on stage holding a stargazer lily and talks about how plants have to get their energy from the sun and their water from what their roots can capture, and how they have to be specifically adapted to their place. A “living building” is similarly self-sufficient, making its own energy, collecting its own water, and even making a positive contribution to the environment. The seven categories of LBC assessment include place, water, energy, and materials, but also three that are less technically focused: beauty, health and happiness, and equity.

The International Living Future Institute awards full Living Building certification only to buildings that meet the standard in all of those categories. Fewer than 40 buildings have achieved such certification to date; YDS’s Living Village aims to be one of them.

Besides being a demonstration project for a new level of sustainability, the Living Village’s main reason for being is to provide on-campus housing for students, not only to offer a more affordable option but also to restore a sense of community that was diminished when the school eliminated the housing in the Quadrangle in a 1990s renovation. (The school still has a block of apartments, originally built in the 1950s for married students, but they have not aged well.) “We train people to build communities,” Sterling says. “So we think they need to have a model for that while they’re here.” Jennifer Herdt, the Gilbert L. Stark Professor of Christian Ethics at the school, says that promoting community is especially important today. “We’re hearing about the epidemic of loneliness,” she says. “And if people in a divinity school are not tuned into this and are not thinking carefully about how to respond, then who is?”

Architect Jason Jewhurst of Bruner/Cott says that the Living Village promotes community by emphasizing common space. The building will have studio apartments, “microunits” with shared kitchens, one-bedroom and two-bedroom apartments, placed among communal kitchens, common rooms, and study spaces. These are all arranged around a courtyard that Jewhurst says is small enough to promote intimacy. “Beyond about 100 feet, you can’t recognize somebody or make eye-to-eye contact,” he says. “We know that from medieval cities.”

And what are the features that make it a “Living Building”? How much time do you have? For starters: the roof will be covered with photovoltaic solar roof tiles that will generate 105 percent of the building’s energy needs; there is an elaborate system to collect rainwater for irrigation and laundry and to treat wastewater for reuse in toilets; the building materials are free of harmful chemicals and regionally sourced to reduce carbon emissions; and the grounds will feature an orchard and a kitchen garden to grow food on the site.

But the process of making a Living Building doesn’t end when the residents move in. In order to ensure that it continues to use resources wisely, students and staff will have to monitor measurements like energy and water use and adjust their behavior as needed. “That means people can’t take 30-minute showers, or their neighbor may not have water,” says Sterling. “You’ll have to do things in moderate ways.”

Herdt thinks students can get behind that idea. “We are in an era of a new kind of asceticism that is honoring embodied existence and the natural world but recognizing that that involves living within limits. And our students really get this; they think it’s natural to connect their ecological commitments with their theological commitments.”

This connection goes beyond just the Living Village. The Divinity School has in recent years embraced the study of what some call ecotheology. In 2017, the school launched a program offering its master of arts in religion (MAR) degree with a concentration in religion and ecology. The school also offers a joint degree program with the School of the Environment.

“If you want to boil ecotheology down,” says Sterling, “it’s the recognition that we are part of creation and are answerable to God for the way we care for creation. We’ve already proven we can harm it, but we’ve got to learn how to help.”

The idea of Christians having an obligation to care for God’s creation doesn’t sound controversial, but it stands in opposition to a reading of the book of Genesis that became dominant in the early modern period, in which God gives humankind limitless “dominion” over the earth. Many Christians have treated this mandate as a broad license to exploit the world’s resources for human benefit.

“But that is such a distortion,” says Herdt. “If you think about the biblical picture, it’s a picture of a world that is the creation of a loving God. So it’s not just stuff out there. It’s stuff that is beloved. Stuff that is created for communion. ‘Dominion,’ properly understood, is about being God’s representative in the natural world to make sure that God’s purposes are being served.”

The Living Village project was adopted as a goal for the school in 2015, Sterling’s third year as dean, and the road to beginning construction last fall was a tortuous one. The school had some funding in place by 2020, but the COVID-19 pandemic delayed the project. Post-pandemic inflation in the building industry led to a whopping 27 percent jump in the cost of Phase One. Sterling says he went back to the original major donors, explained the situation, and “to a person, everyone made a commitment to help.”

The 51 beds in Phase One are not going to be enough to accommodate the number of students who might want to live in the village. Sterling hopes to build Phase Two, another Living Building similar in size to Phase One, on the site now occupied by those 1950s apartments. For Phase Two, Sterling says, the school still has to identify a lead donor.

But even two state-of-the-art sustainable buildings feels like a drop in the bucket given the climate challenge we face. Asked how optimistic he is about his approach to building catching on, Jason McLennan says, “The movement continues to grow, but the rate of decline in the health of the planet continues to outstrip the gains we’re making. But we have the solutions we need to address climate change when we’re ready to implement them.” About the Living Village, McLennan says he hopes “it’ll change the lives of thousands of people, and that they’ll remember this project as a beacon of hope.”

Teresa Berger, Professor of Liturgical Studies and Thomas E. Golden Jr. Professor of Catholic Theology, has a similar idea but puts it slightly differently. “Hopefully the Living Village will shape its inhabitants in such a way that they will leave here and be dissatisfied with anything less than Living Villages wherever they go.”

loading

loading