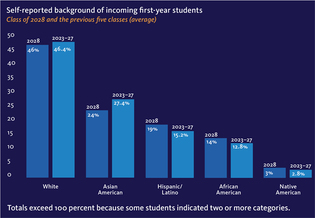

Chart: Jeanine Dunn. Data: Office of Undergraduate Admisssions.

When the US Supreme Court decided in June 2023 to bar universities from considering an applicant’s race in the admissions process, the country’s institutions of higher learning braced for major changes to the demographic composition of their classes. In particular, they worried that enrollment among underrepresented groups would decline in the absence of affirmative action programs. Now that statistics are in from colleges around the country for the Class of 2028, the results have varied. At Yale, though, the proportion of African American and Hispanic/Latino students in the first-year class was essentially unchanged from last year.

African American enrollment in the Class of 2028 was 14 percent, the same as the previous year, and Hispanic or Latino enrollment was 19 percent, higher by one point. White enrollment increased by four percent, while Asian American enrollment decreased by six percent. (See the chart above for a comparison of this year’s demographics with an average of the five previous classes.) At Columbia and MIT, in contrast, Black enrollment declined by 8 and 10 percent, respectively, to 12 and 5 percent, and at Harvard it fell to 14 percent from 18 the previous year. Asian American enrollment in Columbia’s Class of 2028 was 39 percent, compared to 30 the previous year, and at MIT it increased from 40 to 47 percent. The percentage of Asian American first-years at Harvard was 37 percent, the same as last year.

Before oral arguments in the Harvard case began at the Supreme Court, Yale joined 14 other universities in defending affirmative action, citing the gains of the last 50 years. Meanwhile, as the court heard its arguments, Yale went to work, preparing for the possibility that the plaintiffs would prevail. The university spent a year drawing up contingency plans, coordinated by the Office of Undergraduate Admissions and the Office of the General Counsel, to sustain diversity on campus in a world after affirmative action.

Yale unveiled those plans in September 2023, less than three months after the court released its decision. “The Supreme Court’s ruling changed the interpretation of the law,” wrote Yale College dean Pericles Lewis and dean of undergraduate admissions Jeremiah Quinlan ’03 in the announcement, “but it did not change our community’s values.”

To comply with the new legal landscape and preserve diversity, the admissions office developed a three-pronged approach. They sought to increase the overall applicant pool by expanding the university’s outreach initiatives. They incorporated new data, like levels of economic mobility in a candidate’s census tract, into the dashboard that each of the university’s three admissions committees use to evaluate applicants, and they refined their criteria for identifying candidates from rural settings and small towns. And they expanded the recruitment process after offers of admission had been sent out, investing more resources in the cultural centers on campus to help them engage prospective Yalies. The admissions office also spent the months between the Supreme Court decision and the following admission cycle retraining all of its alumni interviewers and committee members to adjust to the new ruling.

The Class of 2028 looked similar to last year’s class in other ways, as well: the proportion of legacy students (11 percent) was the same, as was the proportion of first-generation college students (21 percent). The proportion of students who are eligible for federal Pell Grants—a common proxy measure for low-income students—was up from 22 percent to 25 percent, a new record high. But Quinlan says that jump was mainly due to a change in the criteria for Pell Grants, which made more students eligible. The number of low-income students, he says, was similar to the previous year.

loading

loading