Yale Alumni Weekly

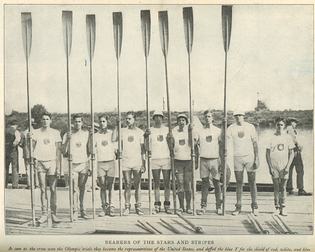

The 1924 Yale varsity eight“doffed the blue Y for the shield of red, white, and blue” when they represented the United States in the Olympics. At far left is future pediatrician and author Benjamin Spock ’25.

View full image

Yale rowers were well represented at this summer’s Olympic games in Paris: sixteen students and alumni rowed in various events for nine countries, and eight of them brought back medals. One hundred years ago, Yale made an even bigger splash in Paris: the entire Yale men’s varsity eight represented the United States in the 1924 Olympics, winning the gold medal and earning their own place in rowing history.

In those days, the US did not assemble a crew of the nation’s best rowers for the Olympics. Instead—as anyone who read The Boys in the Boat will know—entire crews from around the country entered a set of trials for the right to represent the nation. But when the Yale crew began its season in the fall of 1923, they had no expectation of going to Paris.

Yale’s Graduate Rowing Committee, an alumni group that oversaw the sport, had decided that the crew shouldn’t compete in the trials, because the Olympics would conflict with the most important event on Yale’s calendar: the annual four-mile race with Harvard at New London in June. The crew would have to interrupt its preparations for the Harvard race to train for and compete in the trials, which would be a much shorter course of 2,000 meters (about one and a quarter miles).

As Yale historian Thomas Mendenhall ’32, ’38PhD, later wrote, “In the isolationist America of the 1920s, many alumni considered the Harvard race more important than the Olympics. Others were still convinced that it was impossible for the same crew to race successfully at 2,000 meters and at four miles.”

But as the season went on, it became clear that Yale’s eight was something special. A year earlier, the Bulldogs had hired the University of Washington’s Ed Leader as their new head coach, and Leader had turned the program around with new coaching and training techniques from the West Coast. His Yale athletes learned quickly. Among them was Benjamin Spock ’25, later a famous pediatrician and author. Spock would earn a spot in the 1924 varsity boat—and eventually an Olympic gold medal—after another rower was injured during the winter.

By May, the varsity eight was still undefeated, prompting suggestions in the press that it was the crew’s duty to try to compete for its country. On June 1, just 12 days before the Olympic trials and seven weeks before the Paris games, the crew met with the rowing committee and made their case. In the Yale Alumni Weekly later that summer, rower Reginald Barnard ’24 and alumnus John Goetchius ’94S described the students’ point of view. “Their attitude was that it was a thoroughly honorable undertaking” and that “the worst that could happen was to go down to an honorable defeat.”

They got the green light. The next day, Leader started training the rowers for the 2,000 meters. After their final exams, they traveled to Philadelphia for two days of trials on the Schuylkill River.

Their toughest competition would be not a college crew but a boat of eight Naval officers, four of whom had been on the Naval Academy’s 1920 crew that won gold for the US at the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp. In the final heat, before an audience of 20,000 people, Yale and the Navy grads went neck-and-neck for most of the race. With a strong push in the last hundred yards, reaching a nearly unheard-of 40 strokes per minute,* Yale won by a mere five feet.

There was little time to celebrate—the crew had just six days in New London to train for the four-mile race with Harvard. On June 20, they dispatched the Crimson by three boat lengths in a leisurely trip down the Thames. A few hours later, at midnight, they caught a train in New London that would take them and their racing shells to New York City, where they boarded the ocean liner Homeric for their crossing to France.

In Paris, they got reacquainted with the 2,000-meter distance and accustomed to the Seine. Their practice times were closely watched, and they soon became the betting favorites in the race.

They faced Great Britain, Canada, and Italy in the final on July 17. Barnard and Goetchius wrote that in earlier heats, the Yale crew had noticed that when the French race official shouted “Partez” to begin the race, “you can see ‘Partez’ coming out of his brain and up through his throat, so we were away on the first letter ‘P’ to a perfect start.”

They hardly needed that edge, though; Yale led the entire race, finishing sixteen seconds ahead of second-place Canada. The New York Times declared on the next day that “the Yale varsity crew will go down as one of the great eight-oared crews in history.”

Thirty-two years later, another Yale crew won the chance to represent the US at the Olympics. Since the 1956 games in Melbourne, Australia, were held in November and December, there was no conflict with the Harvard regatta. Once again, Yale’s crew won the gold for their country.

__________________________________________________________________

* In our print edition and in the original online version of this article, we erroneously reported that the crew rowed at 40 strokes per second, which would indeed have been impressive.

loading

loading