Manuscripts and Archives

Asakawa in his later years as a Yale professor.

View full image

Manuscripts and Archives

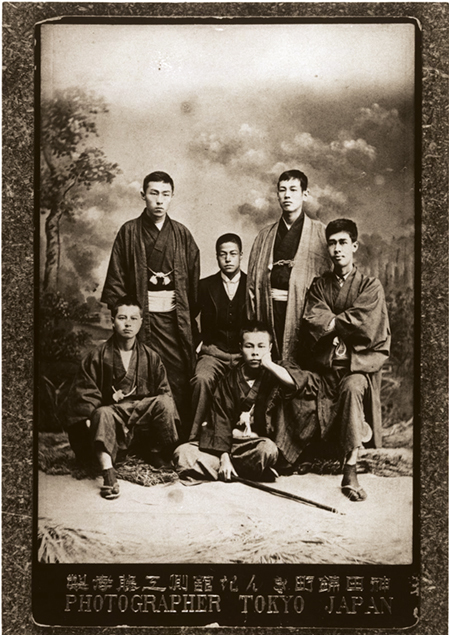

Kan-ichi Asakawa is in the center of this group photo, taken with his friends in Japan before he departed for Dartmouth College.

View full image

Every summer, ten middle school students from Nihonmatsu, Japan, file into New Haven’s Grove Street Cemetery with their chaperones and a dignitary or two from their town—sometimes the mayor. They find the grave marker they’re looking for, lay flowers in front of it, and observe a reverent moment of silence.

This ritual has been going on since 1991, except for an interruption during the COVID-19 pandemic. The students, chosen for the trip by a competitive process, are there to pay tribute to Kan-ichi Asakawa 1902PhD (1873–1948), a native of Nihonmatsu who spent his last 42 years in New Haven.

A scholar of Japanese feudalism, Asakawa was on the history faculty at Yale—the first Japanese person to receive a faculty appointment at a major American university. Besides visiting Asakawa’s grave, the students look at selections from his papers at the Beinecke Library, visit the East Asia collection in Sterling Memorial Library, and stop at a memorial garden dedicated to Asakawa in Saybrook College, where he lived as a resident fellow.

Asakawa’s interest in feudalism was more than theoretical: he was himself the son of a samurai, heir of a family who had fought on the losing side in the war that led to the Meiji Restoration. At Waseda University in Tokyo, Asakawa became a Christian and met the Reverend Tokio Yokoi, who in turn connected the young scholar to the Reverend William Jewett Tucker, president of Dartmouth. Tucker, who would become a kind of second father to Asakawa, arranged for him to come to Dartmouth as a scholarship student. “If you were in the network of Christians and missionaries in Japan, you had access to knowledge about the Western world,” says Daniel Botsman, the Sumitomo Professor of History at Yale and a scholar of nineteenth-century Japan, “and in an era where the whole country is focused on westernization, that was a good way to get a leg up.”

It was at Dartmouth, at Tucker’s urging, that Asakawa began to consider making an academic career for himself in the United States instead of returning to Japan. “If my training in this country be such that it may be used for greater benefit abroad than at home, I must follow the former line,” he wrote to a friend in 1899. After graduating from Dartmouth that year, he was admitted to graduate school at Yale, where, in 1902, he became the tenth person to receive a PhD in history from the university.

Asakawa returned to Dartmouth as a lecturer in “the history and civilization of the Far East,” but world events soon opened other avenues for him. In February 1904, war broke out between Russia and Japan, and Asakawa was uniquely suited to explain the conflict to a curious American audience. By the summer, he had delivered more than 20 lectures about the war and the issues behind it. He wrote articles on the subject for Collier’s and the Yale Review, and in November 1904 he published a book about the war. When peace talks were held in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in August 1905, Asakawa was on hand.

In 1906, Yale appointed Asakawa as an instructor in the history of Japanese civilization and as curator of Japanese and Chinese collections in the library. Botsman suggests Asakawa’s emergence as a kind of public intellectual may have piqued Yale’s interest. “I think the fact that he had become a figure who could talk with authority about affairs in the Far East was what led people to think ‘Oh, we should have this person here instead of letting him go back to Dartmouth,’” he says.

Before Asakawa began his work in New Haven, though, he returned to Japan for a year to work on another project. Asakawa had a vision to establish a library of important Japanese texts in the United States. When that proved impractical, he arranged to collect books for Yale and for the Library of Congress, forming the nucleus of collections that are still significant today.

At Yale, Asakawa taught both Japanese and European history, extending his interest in Japanese feudalism to that of Europe and juxtaposing the two at a time when even comparative history didn’t usually include East Asia. Asakawa never did attract a following among undergraduates, though; it has been suggested that his lectures were dry and his personality rather formal and forbidding. His diaries make clear his disdain for proms, sporting events, and student tomfoolery; he was consistently bookish and for fun would write essays on Hamlet or other intellectual topics beyond his specialty.

He also kept his eye on international affairs. Having spoken up for the Japanese cause during and after the Russo-Japanese War, he was dismayed to see his home country renege on promises in the Treaty of Portsmouth regarding Manchuria and Korea. In 1909, he wrote a book called Japan’s Crisis, warning presciently that Japan’s growing militarism would eventually lead to war with the United States.

In 1905, Asakawa had married Miriam Dingwall, a dressmaker from New Haven he had met while in graduate school. She died in 1913 while recovering from surgery. They had no children. “I discover now that I had been too reserved to her in my expressions of sentiment,” he wrote shortly after her death. “She often appeared to note with concealed disappointment that I put my work before her.” He never married again.

But Asakawa always had his work. And in 1929 he published his most important piece of scholarship. In 1917, he had traveled to the Japanese island of Kyushu to review and copy documents from the collection of a family of local gentry spanning more than 600 years. Asakawa translated the documents into English and published them with extensive commentary as The Documents of Iriki, providing an extraordinary look at the evolution of social structures across the entire feudal period. “The tragedy of that book is that in the introduction he says that he intended it as just a preliminary study to be followed by a broad interpretive history of feudalism in Southern Japan,” says Botsman. “But he never managed to write that book, in large part because he was such a painstakingly careful scholar.”

Asakawa’s approach, using local records to explore social and institutional change over long periods of time, was consonant with the budding social history that scholars like Marc Bloch were pioneering in France. (Asakawa and Bloch in fact exchanged letters in the 1930s.) It would be decades before social history came into its own in the United States.

Besides his scholarship, Asakawa had a number of outside initiatives. He was a go-to source for Japan-related questions, consulting with the Remington company on a Japanese typewriter and with the Brooklyn Museum on Japanese inscriptions for their building’s façade. And for years, he was intimately involved in the International Auxiliary Language Association, which sought to create a common world language called Interlingua. “It was in keeping with his diplomatic interests—that idealistic idea that we can connect the world,” says Haruko Nakamura, librarian for Japanese studies at Yale, who has researched Asakawa’s role in the organization.

Meanwhile, Asakawa struggled to be taken seriously at Yale. From 1910 to 1933, he was an untenured assistant or associate professor, combining his teaching duties with curatorial duties at the library. In 1933, he was appointed a research associate in history. Three years later, he wrote to President James Rowland Angell to suggest that, however innocent the university’s intentions, the title was giving colleagues in Japan “the impression that I had been side-tracked or shelved” and hinted that they might see a kind of racism in the gesture. The next year, he was appointed a full professor with tenure at age 64. In a letter to Dartmouth president Ernest Hopkins, Angell admitted that Asakawa “has been very shabbily treated here. . . . In recent years we have dealt more decently by him, but in earlier years the record was really quite wretched.”

Asakawa’s final years on the faculty were darkened by Japan’s growing aggression in the Pacific, imperiling the friendship he had always championed between Japan and the United States and vindicating his warning from 30 years before. As war between the two countries seemed inevitable, Asakawa and a friend, the Harvard historian of East Asian art Langdon Warner, hatched a Hail Mary of a plan. Drawing on his understanding of Japanese culture, Asakawa drafted a letter for President Roosevelt to send to Emperor Hirohito, a last-ditch diplomatic effort to avoid war. Warner had connections in the federal government, and he told Asakawa he would get the letter to the president. “I realize that the chances are one in a million,” Asakawa wrote to a friend. “But I pray that a miracle be granted.”

The letter Asakawa wrote for FDR, just two weeks before Pearl Harbor, urged the emperor to a complete change of course away from war, appealing to his sense of honor and history in a way Asakawa believed would be most effective. “Your loyal people would be relieved of the crushing burden weighing upon their mind and body, for which they have hardly been responsible”; it read, “and all the nations near and far would find themselves freed from the fears of continued and fresh calamities caused by what they cannot regard but as an unfortunate error. Everyone would immediately comprehend and applaud so noble an act of complete self-conquest.”

The letter did find its way to the White House, but it was not sent to Hirohito. Roosevelt sent a different message to the emperor on December 6 that Asakawa later said would have had no chance of working; in any case, the emperor wasn’t shown the letter until moments before the attack on Pearl Harbor began.

Once the war began, the university offered its support to Asakawa, who was not an American citizen. On December 8, the day Roosevelt declared war, Yale president Charles Seymour ’08 wrote to Asakawa his assurance that “all that lies within the power of the university will be done to keep your internal life normal.”

One tangible thing they offered was a place to live. Asakawa had been living in Saybrook College as a resident fellow, but he was slated to retire in the spring of 1942. Normally, he would have been required to leave his fellow’s apartment, but Yale, worried that he might face discrimination in looking for a place to live, offered to let him stay as a kind of “sanctuary,” as Asakawa described it. He declined, but he accepted an apartment in the Hall of Graduate Studies, where he apparently stayed for the rest of his life.

Asakawa was always reassuring in his letters to friends that he was treated well during the war. He wrote in February 1942 of going to the local FBI office as an “enemy alien,” but added that “the FBI man—Mr. Fisher—who looks after the aliens in the university is extremely friendly, and says I should let him know if I had any difficulty.” In the same letter, he allowed that “it is getting a little hysterical in California.”

In 1943, there was a reception for Asakawa in the courtyard of Sterling Memorial Library, perhaps in honor of his retirement from his curatorial duties there. He had written remarks in case he was called on to speak. No such request was made, but the text is preserved in his papers. “I always marvel how through these long years my colleagues in the library and in the university could have been so tolerant of me as they have been,” he wrote. “I say this, because I know that I am still not acclimatized to American life, not any more than I was to my native country. I am neither a complete Occidental nor a complete Oriental; I am neither here or there.”

The university community was the closest thing Asakawa had to a family in his later life, as became apparent when he died in 1948 at age 75 while vacationing in New Hampshire. It fell to the dean and staff at the Graduate School to deal with his books, papers, and personal effects, and to answer inquiries and condolences from friends here and abroad.

Asakawa’s legacy as a symbol of peace grew in Japan in the years following his death, a time when the country was rebuilding and dealing with the consequences of its imperialism. “The thing that made him appealing in the context of postwar Japan was that he was vehemently anti-Communist, and he was also someone who had said Japan shouldn’t go to war against the US,” says Botsman. “Most of the people who had been critical of militarism in Japan had been Communist or left-leaning. So here was this guy who was not a leftist, who was critical of the military and obviously very sympathetic to the US.”

The memorial garden in Saybrook College was dedicated in 2007 to commemorate the centennial of his joining the Yale faculty. Designed by the landscape architecture firm Zen Associates, it features stones, a rain pool, Japanese maples, and bamboo in a small walled space in the corner of Killingworth Court—an appropriate monument to a man of understatement and quiet introspection.

The other monument to Asakawa at Yale is the library collection he built and curated for 37 years. With help from Yale alumni in Japan, he continued to add to the works he collected in 1906. Botsman says that Yale’s collection of pre-modern Japanese manuscript materials is “widely considered the best at any university outside Japan.”

Botsman, for one, is grateful. “It’s been one of the joys of being here, frankly, having access to all that.” Surely nothing would please Asakawa more.

loading

loading

4 comments

Thank you for such a beautifully written story about this man's life.

I agree with your perspective on the memorial.

As someone who grew up in Japan, but never knew of Asakawa Sensei, I appreciate this very complete account of the life of an extraordinary man.

As a librarian at Yale and occasional docent for the Grove Street Cemetery, I have long admired Kanichi Asakawa for his contributions to scholarship and diplomacy. Thank you for this illuminating article.

I was interested to read here that the Brooklyn Museum consulted him on the "Japanese inscriptions for their building’s façade."

It reminded me that he was likewise consulted on the Chinese inscription carved into the front façade of Sterling Memorial Library. According the 1931 Yale Library Gazette [1]: "This inscription, selected and translated by Professor Asakawa, is in a writing of the eighth century, taken from a rubbing of an epitaph, carved in stone, of the Yen family, illustrious in Chinese history for the high literary attainments and the patriotic acts of several of its members".

[1] See p. 84 in https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=yale_history_pubs