From the book “Borden of Yale”

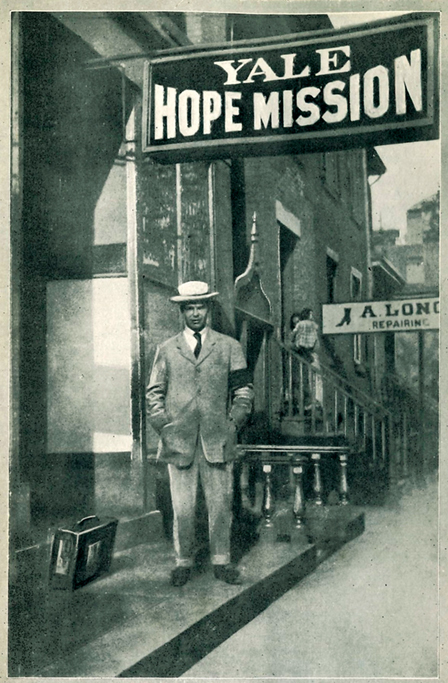

William Whiting Borden ’09 posed in front of the newly opened Yale Hope Mission—at its original location on Court Street—in 1907.

View full image

From the book “Borden of Yale”

William Whiting Borden ’09 posed in front of the newly opened Yale Hope Mission—at its original location on Court Street—in 1907.

View full image

Mark Alden Branch ’86

The mission's second home, completed in 1929, was at 305 Crown Street. The building is now owned by Yale.

View full image

Mark Alden Branch ’86

The mission's second home, completed in 1929, was at 305 Crown Street. The building is now owned by Yale.

View full image

Most Yale alums recall the building at 305 Crown Street, if they remember it at all, as a kind of catch-all, a place that has housed student organizations, faculty offices, and the Kosher Kitchen. But from 1929 to 1968, 305 Crown was home to a mission that provided a bed and a meal to alcoholics and other homeless men, along with a dose of evangelical Christianity.

It was John Magee, Class of 1906, who first conceived of the Yale Hope Mission, when he was secretary of the Dwight Hall YMCA. In 1906, he pitched the idea to sophomore William Whiting Borden ’09, a devout evangelical from Chicago whose father had made a fortune in silver mining. Borden jumped in enthusiastically.

Magee and Borden patterned their project after New York’s pioneering Water Street Mission, which had been founded in 1872. They hired Louis Bernhardt, who himself had been converted at Water Street, to run it.

Magee and Borden wanted to convert Yale men as much as they did homeless men. They enlisted students to volunteer at the mission, believing that seeing religion change the lives of broken men would deepen the students’ faith. As Borden wrote home to his mother, “It would be great!—just the thing to take a few sceptics down and let them see the Spirit of God really at work regenerating men.”

The mission opened in March 1907 in rented rooms on Court Street near Wooster Square. Before long, Borden had bought the whole building. His fellow volunteer Charley Campbell ’09 wrote that “we now have downstairs dormitories and shower baths, and a place in which clothes can be fumigated, as well as a good, inexpensive lodging-house upstairs. . . . For two dollars a week a man can have a room to himself, a little home.”

Borden’s contribution was more than financial. “Bill was heart and soul in it all,” Campbell recalled. “It was great to see him on those meetings—so earnest in his presentation of the truth and in dealing with those who came forward for prayer. Afterwards, he would often take men around until he could find a place for them to sleep, and pay the lodging-house charge himself so as to avoid putting temptation in their way by giving them money.”

After graduating from Yale in 1909, Borden went on to Princeton Theological Seminary for a graduate degree and became an ordained minister. He died in 1913 of meningitis in Cairo, where he was training for missionary work.

But the mission lived on, both as a resource in the New Haven community and as a volunteer opportunity for Yale students. By 1928, Yalies had helped raise the money for a new three-story building at 305 Crown. At the time of the building’s dedication in March 1929, the Yale Daily News reported that “an undergraduate committee of 36 men . . . take charge of the Monday and Friday evening services, as well as the jail, hospital, and church visitations.”

As late as 1967, students from Dwight Hall were still volunteering at the mission, and it was supported by the Yale Charities Drive. But by then, its end was near. Herb Cahoon, director of Yale Volunteer Services and a member of the mission’s board, told the News that the mission had become “a revolving door” for alcoholics with no rehabilitation program. Another board member, Dwight Hall general secretary David Byers, blamed gentrification. “The luxury apartments across the street don’t like the idea of having a mission for alcoholics around,” he said. It closed in 1968.

Borden’s philanthropy and missionary zeal have made him a hero and role model in evangelical circles for more than a century, in part thanks to a 1926 biography by Geraldine Taylor. In the book, she wrote that when missionary leader Henry W. Frost, a mentor of Borden’s, asked “a much-travelled visitor” what had impressed them most on a trip to America, the reply came without hesitation: “The sight of that young millionaire kneeling with his arm around a ‘bum’ in the Yale Hope Mission.”

loading

loading