loading

loading

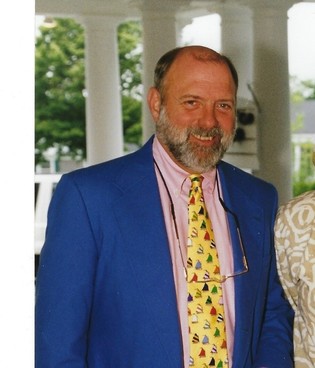

ObituariesIn Remembrance: George Briggs Rowland ’60, ’65MD, ’79MPH Died on January 2 2018 View full imageDr. George B. “Robin” Rowland, a healthcare executive who spent an entire career striving to improve how medical systems care for patients, died January 2 at his home in Escondido, California. He was 79. Rowland was a much beloved husband, father, grandfather, friend, and colleague who loved art, music, and especially singing, be it in the choir, a chorus, or in a pickup folk duet with a favored brother. He cheered religiously for the Boston Red Sox and New England Patriots, and he enjoyed a tall glass of rum and soda at the end of the day, garnished with limes picked from his own backyard garden. A Yale-trained doctor who enjoyed a privileged New England upbringing, Rowland’s life took a profound turn when he moved in the mid-1960s to the Navajo Nation reservation to work as a clinician for the federal Indian Health Service. The move to a stark and beautiful Arizona landscape inspired a lifelong love of the West. And working for a cumbersome bureaucracy permanently altered the trajectory of his career, steering him away from clinical care into high-level administrative roles that allowed him to combat inefficiencies and dysfunction in health care. He went on to manage large county health systems and hospitals as director of the Maricopa County (Arizona) and San Luis Obispo County (California) health departments during the 1970s and 1980s, devising ways to streamline and modernize the complex agencies responsible for delivering care to indigent populations. He later worked as a self-employed health-care consultant, and also as an executive at Cape Cod Healthcare in Massachusetts, where he led efforts to enhance quality and safety and improve behavioral health treatment. The cause of his death was idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, said his son, Christopher Rowland, a reporter for the Boston Globe. The respiratory disease sapped his ability to move about his California home in his final weeks, but the struggle to breathe did little to diminish his inquisitive and lively mind. He analyzed all aspects of his own care and created detailed, end-of-life plans that he shared with his extended family as well as San Diego–area medical students who visited his home as part of hospice training. “A good death is a death well planned, with wishes of the dying fulfilled, without too many surprises, with healing of past wounds, and with family and friends surrounding one with love at the time of death,” Rowland wrote in December. George Briggs Rowland was born on May 21, 1938, in Boston. He was the son of the late Benjamin Allen Rowland, who worked to revitalize old mill buildings in Lawrence, and the late Sara Briggs Bolton. He was the middle child of five raised at Pine Lodge in Methuen, Massachusetts, before the family sold the sprawling property in 1957 to the Sisters of the Presentation of Mary. His paternal grandmother was a cousin and heir of Edward Francis Searles, a renowned Gilded Age interior decorator who built the estate. He attended the Brooks School, in North Andover, before enrolling at Yale as an undergraduate student and then in the Yale School of Medicine, earning his medical degree in 1965. Summers were spent in Osterville, on Cape Cod, where the family had a shingle house overlooking Nantucket Sound. He spent countless hours on the Wianno Club tennis courts and warm Wednesday nights at club dances. He also spent much time at an old family farmhouse in Londonderry, Vermont. Married three times, he spent the summer after his first marriage clearing ski trails at nearby Stratton Mountain. Rowland received his military draft notice midway through the first year of his residency in internal medicine at the University of Kentucky, in 1966. He signed up as a commissioned officer with the Public Health Service assigned to the Indian Health Service on the Navajo reservation, moving his young family into government housing next door to the government clinic he ran. He said he was not opposed to the Vietnam War and was not active in peace protests, but he did not want to become a surgeon, which he believed would have been his path in the military. So he packed up for Chinle, Arizona, and a job in front-line clinical care for Native Americans, many of whom herded sheep and still lived in traditional homes called hogans. “I certainly didn’t know anything about the Indian reservations. I didn’t know anything about the Navajo. When I learned that 70 percent of my patients didn’t speak English, I was dumbfounded,” Rowland said in a recent interview with his son. Delivering primary care was a challenge across a vast landscape, with few telephones and primitive roads. The Indian Health Services doctors took turns leaving the lights on outside their tract houses, so patients would know which one was on call. “They came in on wagons and horseback and trucks and all sorts of stuff,” he said, describing how he strove to build credibility across the cultural divide. He said he identified a leaking brain aneurysm early, which likely saved the life of a patient, a tribal elder, and cured the horse of another important tribe member. “I called a veterinarian in Albuquerque and he suggested I give the horse a dose of steroids and antibiotics, so much per pound,” Rowland said. “I went to the clinic and cleaned out our supply of both those items and started an IV, and next morning the horse was up and around. Word spread far and wide.’’ Rowland undertook a number of initiatives. He hired community health workers, developed a chronic disease registry, and trained a Navajo nurse to treat minor conditions. He established a satellite clinic at a tribal school in the remote reservation outpost of Rough Rock, working with tribal members on a culturally sensitive design. He and tribal members even had the facility blessed by a medicine man. But he clashed with Indian Health Service superiors in Albuquerque, who Rowland felt did not sufficiently support the school clinic. By the late 1960s, Rowland had begun wearing cowboy boots and long hair beneath his cowboy hat, along with the khaki military uniform of the Public Health Service. Rowland said his superiors increasingly viewed him with suspicion, believing he had “gone native.” And Rowland was infected with a lifelong urge to find ways to fix health care systems. In 1968 he left the reservation and went to work for the federal Centers for Disease Control in Phoenix, using his experience in disease registry to track cases of tuberculosis throughout Arizona. In 1970, he joined the Maricopa County Health Department and eventually rose to the top post of director of health services, running a 500-bed county hospital serving greater Phoenix. In 1982, he moved to San Luis Opisbo as director of health services for that California county. In the early 1990s, he struck out on his own as a consultant and moved back to Cape Cod. Rowland maintained a lifetime love of singing, especially in church choirs, but also folk music. He deeply enjoyed gardening and birding. He sailed in two Newport-to-Bermuda races in the 1950s, and, in the 1970s, two trans-Atlantic races. He sailed from South Africa to the Caribbean with friends in 2002. And he popped a bottle of sparkling wine to celebrate his 75th birthday in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, on a 2013 passage from Puerto Rico to Hyannis. Rowland is survived by his wife, Marie Cassidy Noel Rowland, of Escondido; and four children, Christopher Rowland, of Washington, DC; Alix Rowland, of Durango, Colorado; Ryan Rowland, of Phoenix; and Sean Rowland, of Oceanside, California. He was especially proud of his five grandchildren, all girls. He also is survived by three brothers, Edward S. Rowland, of Hamilton, Massachusetts; Benjamin A. Rowland Jr., of Marblehead, Massachusetts; Daniel Rowland, of Lexington, Kentucky; a sister, Mary Allen Swedlund, of Deerfield, Massachusetts; and a half-brother, Rodney D. Rowland, of New Castle, New Hampshire. Two previous marriages, to Susan Scott Rowland and Elaine Cantrell Petrosino, ended in divorce. He was an examiner for the Malcolm Baldridge National Quality Award, a prestigious prize for health-care organizations, from 2011 to 2013. He volunteered in the Executive Service Corps of New England and was active in Rotary Club of Escondido. He was a congregant at St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church in Poway, California, and at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in Osterville, Massachusetts. Services are scheduled for January 26 at St. Bartholomew’s in Poway, at 1 p.m. Memorial donations may be made to the Audubon Society, the Nature Conservancy, or the St. Bart’s music program. —Submitted by the family. |

|