loading

loading

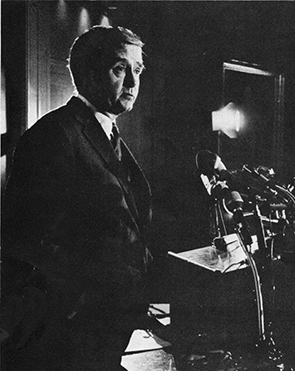

featuresFirst-person stories: Yale administration“In my most difficult year, despite all of Yale’s resources, I was mostly on my own.”  Manuscripts & ArchivesPresident Kingsman Brewster Jr. ’41 resisted coeducation, trying instead to bring Vassar College to New Haven. But when he became convinced it was inevitable, Yale acted quickly. View full imageThese stories were written by women responding to our request for memories of their experiences as the first female undergrads at Yale. See other stories on these topics: In the Colleges, Gratitude, In the Classroom, May Day, and Yale Men. You’ll see that some writers’ names are asterisked. These women submitted their stories also to the Written History Project, founded by the 50th Anniversary Committee so that all alumnae of the time can contribute to the history of coeducation at Yale College. (There’s also an Oral History Project and an Archives Project.) And finally: we invite all readers to send their letters and reactions—including stories of their own experiences of breaking boundaries at Yale—to editor@yalealumnimagazine.com. ___________________________________________ Margaret Coon ’73 The following is excerpted from a contribution to Reflections on Coeducation: A Critical History of Women and Yale (2010) by Emily Hoffman and Isabel Polon. Friday, February 20, 1970—Despite the dreary cold of the New Haven winter, a small group of women and men huddled excitedly to hatch a plan. . . . Tomorrow, Yale’s illustrious alumni would gather for lunch in the Freshman Commons. We saw a great opportunity to deliver an important message: the progress of coeducation at Yale, six months after its launch, was too slow. . . . Many of us experienced the awkwardness of extreme gender imbalance. In a class where one was the lone female, the professor might inquire about “the women’s perspective.” Especially irksome was President Kingman Brewster’s frequent emphasis on Yale producing “1,000 male leaders.” This was the plan: as the alums were enjoying their undoubtedly sumptuous luncheon (cold roast beef, the Times later reported), we would enter the room from the door behind the podium. Then I, though for the life of me I can’t recall how I got nominated, would ascend the stage and ask President Brewster for the opportunity to speak. . . . My best recollection, now 40 years later, is that the plan came off pretty much without a hitch. I climbed the steps, my heart in my throat, and approached President Brewster. In the calmest voice I could muster, I politely asked him for the opportunity to speak. He agreed. I proceeded to deliver a speech of which the central demand was a more rapid pace toward full coeducation. . . . Not to overstay our welcome, we did not remain in the hall long enough to hear President Brewster depart from his prepared remarks to acknowledge the validity of some of our concerns. I have always believed that Brewster wanted to do the best he could by all of us and was still dealing with considerable alumni resistance to change to the all-male bastion. . . . While I can’t claim we significantly aided the positive course of history by our act that February afternoon, I do believe we nudged it forward.

Kristin Houser ’71 I transferred to Yale because I was looking for a more intellectually and socially vibrant place than Wellesley was at that time, and I found that at Yale. I loved my classes—Russian literature, Shakespeare, a seminar on character and political leadership, and Law and Society. I was on the young side (18 as a junior) and came from a poor family in upstate New York, so I was definitely intimidated, but I was fortunate to find friends who were more comfortable in that environment and included me in their activities. At the beginning of senior year, my younger brother committed suicide. In my grief, I walked around campus in a dissociative state and often missed class. I couldn’t sleep and would stay up late in my single room crying. What I think is interesting is Yale’s response. One day, I walked into the counseling office saying I felt dead inside and couldn’t make myself do anything. After listening to my story, the psychiatrist said, “That’s grief, but we don’t really have rituals of mourning in America that allow others to acknowledge and support you through it.” Although he normalized what I was experiencing, he did not suggest that I receive ongoing counseling. After first semester, I got a message to see the Saybrook dean because I had failed two classes. I explained that my brother had died and I wasn’t doing well, and hadn’t attended those classes. He responded that it was unusual to drop classes after they were over, but, under the circumstances, he would arrange for that to happen. So that consequence of my dysfunction was erased from my record—something that probably didn’t happen for kids suffering loss in less privileged surroundings. He also referred me to the college pastor. I went to Dr. Coffin’s house several times for dinner and his wife was very nice to me, but Dr. Coffin never spoke to me about my brother’s death. I am extremely grateful for my Yale education and Yale degree. But, in my most difficult year, despite all of Yale’s resources, I was mostly on my own.

Christiane Citron ’71 The following is excerpted from a 1970 essay for a high school publication. Being at Yale and being a feminist, I find the question of the university's role in bringing about social change a recurring topic of interest. A perfect example of this is Kingman Brewster's reiterated claims of Yale's educational obligation to the nation to educate 1,000 MALE leaders per year. I am outraged at the elitism implicit in this theory! Yale is fully coeducational; it's not just an experiment. However, if it continues its policy of admitting only 250 women per year, obviously only male leaders will be turned out. As society is now structured wholly under male leadership, unless Yale agrees that women are incapable of leadership roles (ignoring the dire shortage of competent professionals in so many fields), the University’s obligation is obviously to take itself out ahead of society and initiate a different admissions policy, so as to provide more women with this so-called leadership preparation. Furthermore, I would dispute the University's role of annually churning out a set of so-called "leaders," and substitute the goal of "capable individuals." Brewster has even refused to meet with members of the Admissions Committee, who have taken the unusual step of publicly stating that the caliber of the boys being admitted for next year is substantially lower than that of the girls who are being turned away. You may have noted in the New York Times recently that the first semester marks for Yale girls were across-the-board higher than for the boys. Being in a hotbed of male chauvinism at Yale has led—amongst my friends anyway—to an extreme view of women’s rights. Recently I have been helping to run an environment office in New Haven and am reminded of a funny, but typical, story that came to our attention. It seems that New Haven College planned a program for Earth Day consisting of an all-male panel of speakers and ending with the crowning of a "Miss Anti-Pollution." Although I disagree with how some of the advocates go about their task—their intense antagonism and hostile attitude, seemingly wanting domination and not just equal rights—I definitely support the Women's Liberation Movement. I regard it as a very healthy drive to both enable and stimulate the maximum realization of our sex's long-neglected and suppressed potential creativity. This movement, in the face of entrenched values and prejudices, is producing the invaluable effects of enhancing the quality of relationships between the sexes, as well as making immense contributions to the general well-being of society. It seems obvious, but nevertheless vital, to stress that Women's Liberation liberates men as well. Our chief effort is to show the invalidity of generalities prejudged on the basis of sexual role. It is those values which so harmfully restrict the woman's opportunities for carrying out a full and rewarding position in society.

Victoria Morgan Amon ’73 Of course there were difficulties at times, such as inevitable roommate clashes (all well-resolved) and occasional snarky comments and behaviors from a handful of disgruntled upperclassmen. Yet overall I strongly believe that the university prepared as well as could be expected for our arrival, welcomed us graciously, and made every effort to integrate women into the fabric of the university. It was very clear that Yale viewed our participation as not just significant, but also critical to its future.

The comment period has expired.

|

|