loading

loading

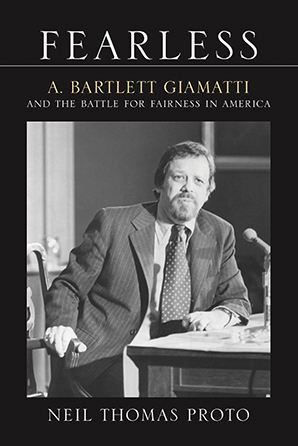

Reviews: September/October 2020 View full imageFearless: A. Bartlett Giamatti and the Battle for Fairness in America With unsteady academic scaffolding amidst voluminous endnotes, the prosecution against Yale is zealous but sometimes based on misattribution. More notably, its text marches to an anti-eugenics drumbeat. The OED defines eugenics as advocacy or study of “the arrangement of human reproduction” in order to achieve desirable population or species changes. Yale, especially in the 1920s and ’30s, was home to a number of prominent supporters of eugenics (including famed economics professor Irving Fisher ’88, ’91PhD, Yale president James Rowland Angell, and medical school dean Milton Winternitz). In this book, however, multiple examples of bias and prejudice against Blacks, Italians, Jews, and Catholics before, during, and after that era are painted with a broad brush as “eugenics.” The study of ethical history is poorly served by fuzzy and provocative labeling. In one example, Reverend (and former Yale president) Ezra Stiles (1727–1795) is criticized as a slave owner and “eugenicist in twentieth-century terms.” Proto questions whether a Yale residential college should later have been named after this slave owner. Yet it is difficult to apply modern mores to past eras without considering the context and without labeling the behaviors accurately. For his time, Stiles was a model of fairness and justice. On assuming the Yale presidency, Stiles freed his slave and publicly sought to promote freedom and reduce the presence of “unlawful” slavery. Bart is the heroic protagonist of this book—but one could extrapolate the biography’s logically troublesome assignments of guilt by association and impugn Bart’s own integrity for his having served as “Master” of Ezra Stiles College for two years in the 1970s. Fearless intentionally avoids wrestling with Giamatti’s time as Yale president and his subsequent governance of Major League Baseball. It tells of Bart’s deep connections to the Italians of New Haven and his fair-mindedness. Yet it leaves us wanting to know how he squared those affiliations with the employee strike that scarred his penultimate year at Yale. We never get close to exploring the internal demons that he faced and which inevitably contributed to his premature death at age 51. In his last 11 years, Bart was at his peak of influence and he performed on a national stage. This lacuna in coverage cries out for attention. Bart himself might have described it in baseball terminology: the reader never reaches home. Proto criticizes what he sees as the elitism of Yale’s historic mission of educating leaders. But he does not reconcile that disdain with his admiration for Bart, nor with Bart’s success in engaging alumni, nor, most importantly, with what was surely Bart’s genuine love for Yale. My own interactions with Bart left me regarding him through rose-colored glasses. In that respect, I have something in common with Fearless. This volume, however, seems to look at almost everything else Yale through the dark fog of eugenics. If only it would allow us to see Bart, and Yale, far more clearly. Dan Oren ’79, ’84MD, associate professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at the Yale School of Medicine, is the author of Joining the Club: A History of Jews and Yale.

|

|

1 comment

-

Neil Thomas Proto, 4:20pm September 11 2020 |  Flag as inappropriate

Flag as inappropriate

The comment period has expired.In his review of my book Fearless, Dan Oren reveals more than he intended; he creates a false narrative.

1. With respect to Bart Giamatti’s tenure as president, I wrote, at the outset, “Giamatti’s presidential papers (exclusive of his speeches) and the papers of those in his administration are not yet available for public examination—a fact of defining consequence to thorough and accurate research and the foundational reason that Fearless stops where it does.”

2. With respect to Giamatti’s tenure as Commissioner of Baseball, I wrote, at the outset, “[C]ertain aspects of Baseball …, previously unexplored, and the values underpinning [Giamatti’s] decision concerning Pete Rose emerged with clarity much earlier in his life and are examined in Fearless.” I have since published two articles on this subject.

3. With respect to “eugenics,” the term applied in the book is “eugenics mentality.” That “persistent mentality” is explained at the outset and is fully documented. Eugenics political advocacy, including sterilization of the “unfit,” lasted decades at Yale and was vigorously applied in Connecticut—including involuntary sterilization of women—by former Yale dean and governor Wilbur Cross. The law remained until the 1960s.

4. Giamatti said Yale’s purpose “is to prepare people for the full claim of citizenship” in a democracy, “[h]ow, in short, we choose a civic role for ourselves.” This belief, however, found its origins in his family life, not in the exclusionary meaning of “leadership” at Yale.

5. Why did Yale pay tribute to a slaveholder in 1959 during the Civil Rights Movement? And why is Oren defending that tribute in 2020? I’ll leave Oren to his own conscience, but characterizing Giamatti as a “Master,” the title of everyone who held that position at Stiles and Calhoun, is the self-constructed petard Oren sits on, in full view: misattribution.