loading

loading

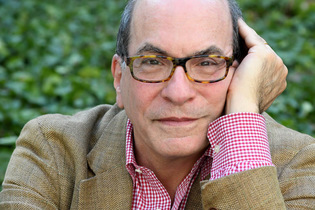

From the Editor"New to the world"Talking to Leonard Marcus '72, a scholar of children’s books.  Sonya SonesLeonard Marcus ’72. View full imageAfter our May/June and July/August issues reported at length on the pandemic and dissected the brutality of racism, we at the Yale Alumni Magazine dearly wanted to deliver something more joyful. COVID-19, let alone racism, won’t disappear soon; we’ll be coming back to those subjects. But for September/October, we turned to children’s books. As Leonard Marcus ’72 told me—and we at the magazine have embraced the concept for this issue—“Children’s smiling is relevant to getting through a crisis.” Marcus would know. According to Timothy Young, the Beinecke’s curator of modern books and manuscripts, he is “the preeminent person in the history of children’s literature in the twentieth century.” When I arranged an interview with him, I was anticipating someone Seussian, full of quirks and quips. But Marcus is a serious scholar; he has lost count of the number of books he’s written about books. He delivered, in crisp, fluent paragraphs, an instant analysis of every book I brought up. The 1845 German book Der Struwwelpeter wasn’t designed to terrify misbehaving children; it’s a comic parody of that kind of lecturing. Horatio Alger was just one among many late-1800s US authors writing rags-to-riches novels—“a good boy and a bad boy, and the good boy always comes out on top,” said Marcus. And Nancy Drew helped girls “see a future of accomplishment for themselves.” When I asked about his own favorite books as a child, he told me something thought-provoking: when he was small, he discovered a Little Golden Book about career choices, “and I pored over that book.” There was nothing especially literary or artistic in it. But his older relatives were constantly asking what he wanted to be when he grew up, and the book helped him answer. Later, that memory showed him “that children very often gravitate toward books for a particular reason having to do with something important in their lives.” (I imagine this also holds true for adults.) That’s one reason he believes the current flowering of books about children of various races, genders, abilities, and other qualities is progress. We talked about Tove Jansson’s books, still among my favorites although I left childhood behind decades ago. There’s “a very big imagination behind them,” Marcus said. “A lot of children’s books are very precious and cozy. But in her books, there’s this feeling of being exposed to the elements and getting through it all, but not without experiencing danger and uncertainty and adventure along the way.” He compared Jansson to Margaret Wise Brown, whose Goodnight Moon rabbit has a warm bedroom but also a window that looks out upon the dark, unknown universe. He brought up William Steig’s Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, in which young Sylvester turns into a rock and seems to be locked in forever, until his parents happen to picnic there—and free him, by talking about their love for him. “There’s a darkness and also a kind of brightness and joy,” Marcus said. In many children’s books I’ve read, the child who is the protagonist pursues long adventures through strange new territory. Sometimes the child has friends and supporters. Sometimes the adventure is spurred by rebellion; think of Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are. But in the end, the child comes home, and is loved. “Children are so new to the world that very little of what happens to them feels familiar, or particularly safe,” said Marcus. “And a story by its nature has a shape that reinforces the sense of order and clarity about life.” We can all use order and clarity in life. Support your fellow humans. And read good books.

The comment period has expired.

|

|