Gerald P. York ’81

Gerald P. York ’81

Yale OPAC

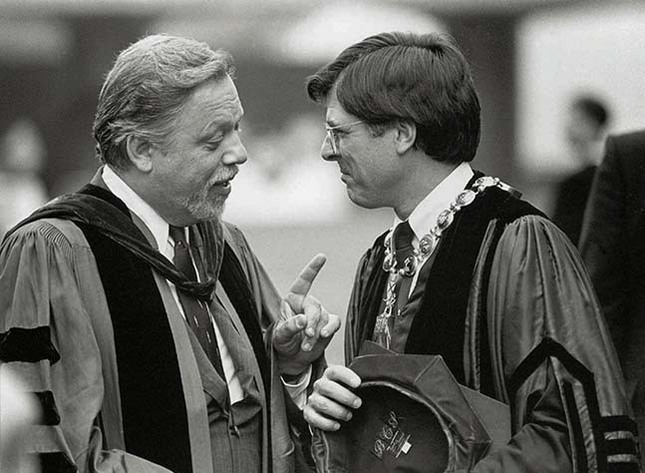

Outgoing Yale president A. Bartlett Giamatti (at left) talks with incoming president Benno Schmidt at Schmidt’s inauguration in 1986.

View full image

Yale OPAC

Outgoing Yale president A. Bartlett Giamatti (at left) talks with incoming president Benno Schmidt at Schmidt’s inauguration in 1986.

View full image

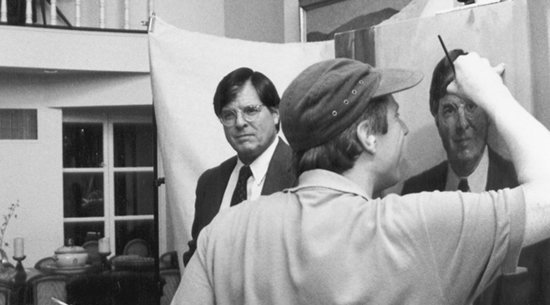

Schmidt posed for artist Gerald P. York ’81 in 1995 at Schmidt’s home in New York City for his official Yale portrait. The painting is on display in the Yale Corporation room in Woodbridge Hall, along with portraits of other past presidents of Yale.

View full image

Schmidt posed for artist Gerald P. York ’81 in 1995 at Schmidt’s home in New York City for his official Yale portrait. The painting is on display in the Yale Corporation room in Woodbridge Hall, along with portraits of other past presidents of Yale.

View full image

T. Charles Erickson

Honorary degree recipients and President Benno C. Schmidt Jr., stand for their photograph in 1987, in front of Woodbridge Hall.

View full image

T. Charles Erickson

Honorary degree recipients and President Benno C. Schmidt Jr., stand for their photograph in 1987, in front of Woodbridge Hall.

View full image

Benno Schmidt Jr. ’63, ’66LLB, president of Yale University from 1986 to 1992, died at the age of 81 on July 9 at his home in Millbrook, New York, following a cardiac arrest. A renowned scholar of constitutional law, he left his position as dean of Columbia Law School to assume the Yale presidency at the age of only 44.*

Schmidt—who was generally called Benno on the Yale campus—is credited with putting Yale on the road to fiscal health at a time when the university’s finances appeared precarious. He inherited a challenging to-do list: relations between Yale and the city of New Haven had deteriorated as New Haven’s economic woes increased. Tension between the university and its lower-paid workers periodically flared up. Then, there was the outsized popularity of his immediate predecessor, A. Bartlett Giamatti ’60, ’64PhD, president since 1978. Moreover, the role of a university president had begun to shift and broaden, adding additional work to Schmidt’s days.

In the years that followed, his attempts at shoring up Yale’s finances by eliminating a percentage of faculty positions, programs, and departments met with hostility from some members of the faculty. Meanwhile, his reluctance to move his family to New Haven (he visited them in NYC on weekends) didn’t always sit well with students who were accustomed to Bart’s seeming omnipresence. Yet Schmidt’s fundraising efforts, which almost doubled the endowment from $1.7 billion to $3 billion; his initiatives aimed at jumpstarting conversations with New Haven community leaders; and his determination to spend money on Yale’s long-neglected and aging infrastructure all continue to garner praise. Says Yale president Peter Salovey ’86PhD: “Benno did so much for Yale and will be remembered for leading much-needed changes to the campus, building the relationship between Yale and New Haven, and advancing our educational mission.

It would have taken longer for Yale to make important changes without him.”

It was Schmidt who first brought in Bruce Alexander ’65, then involved in commercial real estate and urban planning, as an adviser for the university. A few years later—under Schmidt’s successor, Rick Levin ’74PhD—Alexander officially took on the role of vice president for New Haven and state affairs and campus development. “Benno was the president who first got me involved in urban redevelopment in New Haven,” says Alexander, who retired from the university in 2018. “Benno had committed to invest $50 million in the city and asked for advice. I was redeveloping urban projects at the time, and suggested the university begin a similar process adjacent to our campus.”

Headlines during Schmidt’s tenure suggest campus unease with some of his decisions. “I didn’t think the job was necessarily to reflect the consensus,” Schmidt said in an interview with the Yale Alumni Magazine, shortly after resigning as president. “I did what I thought was right. Anyone who takes controversy head-on, who looks at the relationship between the present and the future and refuses to mortgage the future in order to conserve the present, is going to take some knocks.”

The son of an early venture capitalist, raised among Manhattan’s sheltered elite, Schmidt attended the St. Bernard’s School on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, the Phillips Exeter Academy, Yale College, and finally Yale Law School. After graduating, he clerked for Supreme Court chief justice Earl Warren, and then spent two years with the justice department before joining the faculty of Columbia Law School—where he became a leading scholar of the US Constitution, receiving tenure at the age of 29. “Benno Schmidt was a towering First Amendment scholar whose book Freedom of the Press v. Public Access defended the First Amendment tradition in an electronic age,” says Jeffrey Rosen ’91JD, president of the National Constitution Center and a professor at George Washington University Law School. “He put his principles into practice as president of Yale, where he became one of the most vigorous defenders of free speech on campus of his time.”

Along the way, as a regular contributor to PBS, Schmidt moderated panels on the US Constitution alongside Fred Friendly of Columbia’s journalism school and legal scholar Floyd Abrams ’60JD. He even had minor roles in two Woody Allen movies, Hannah and Her Sisters and Husbands and Wives.

Following his resignation as president of Yale, Schmidt became chief executive of Edison Schools, a start-up network of for-profit elementary schools around the country. “Yale and higher education in general are really in very good shape; it’s the best in the world by far,” Schmidt told the Yale Alumni Magazine at the time. “But elementary and secondary education are a lot worse off. It felt a little incongruous to be resting at the apex when the foundations are crumbling.” He subsequently cofounded Avenues: The World School, intended to be an international network of for-profit private schools, from the nursery through twelfth grade. In addition, Schmidt played a major role in restructuring the City University of New York, first as head of a mayoral task force and later as chairman of the board, and he spent almost twenty years on the board of the New-York Historical Society. “Benno’s generous participation in our public programs around constitutional history and law left audiences dazzled, both by his theatrical skills and his incredible breadth of legal and historical knowledge,” says Louise Mirrer, president and CEO of the society. “He will be sorely missed.”

“Yale can’t have been a happy moment in Benno’s life, or he in Yale’s life, for that matter,” says Yale anthropologist Alison Richard, “but he accomplished a lot and left a major and enduring legacy.” Richard—former director of the Peabody, former Yale provost, and former vice chancellor of the University of Cambridge—says that in her career trajectory, all roads led back to Schmidt. “If he hadn’t talked me into being Peabody director (with no qualifications), I’m sure Rick Levin wouldn’t have asked me to be provost (having acquired a qualification as Queen of the Dinosaurs). And without provostery I’m sure Cambridge wouldn’t have asked me to be the vice chancellor. And I’m certain my story is repeated many times over in other lives touched by him in his smart, genial, and persuasive way.”

In his exit interview with the Yale Alumni Magazine in 1992, Schmidt sounded wistful: “It’s not possible to serve at Yale without feeling a sense that this is your family. There are people there I’ve grown to love. It becomes a part of your blood.”

___________________________________________________________________

* In our print edition, we incorrectly indicated that Schmidt's law degree was a JD. It was an LLB.

loading

loading